Quicksearch

Wednesday, June 26. 2013

The audacious plan to end hunger with 3-D printed food

Via Computed·Blg via Quartz

-----

Anjan Contractor’s 3D food printer might evoke visions of the “replicator” popularized in Star Trek, from which Captain Picard was constantly interrupting himself to order tea. And indeed Contractor’s company, Systems & Materials Research Corporation, just got a six month, $125,000 grant from NASA to create a prototype of his universal food synthesizer.

But Contractor, a mechanical engineer with a background in 3D printing, envisions a much more mundane—and ultimately more important—use for the technology. He sees a day when every kitchen has a 3D printer, and the earth’s 12 billion people feed themselves customized, nutritionally-appropriate meals synthesized one layer at a time, from cartridges of powder and oils they buy at the corner grocery store. Contractor’s vision would mean the end of food waste, because the powder his system will use is shelf-stable for up to 30 years, so that each cartridge, whether it contains sugars, complex carbohydrates, protein or some other basic building block, would be fully exhausted before being returned to the store.

Ubiquitous food synthesizers would also create new ways of producing the basic calories on which we all rely. Since a powder is a powder, the inputs could be anything that contain the right organic molecules. We already know that eating meat is environmentally unsustainable, so why not get all our protein from insects?

If eating something spat out by the same kind of 3D printers that are currently being used to make everything from jet engine parts to fine art doesn’t sound too appetizing, that’s only because you can currently afford the good stuff, says Contractor. That might not be the case once the world’s population reaches its peak size, probably sometime near the end of this century.

“I think, and many economists think, that current food systems can’t supply 12 billion people sufficiently,” says Contractor. “So we eventually have to change our perception of what we see as food.”

There will be pizza on Mars

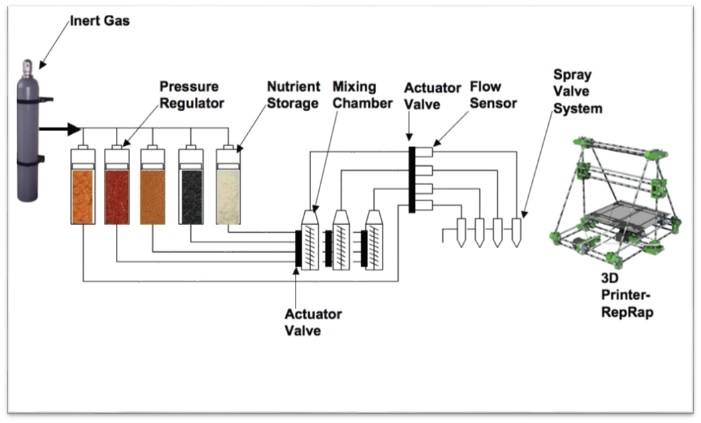

The ultimate in molecular gastronomy. (Schematic of SMRC’s 3D printer for food.)SMRC

If Contractor’s utopian-dystopian vision of the future of food ever comes to pass, it will be an argument for why space research isn’t a complete waste of money. His initial grant from NASA, under its Small Business Innovation Research program, is for a system that can print food for astronauts on very long space missions. For example, all the way to Mars.

“Long distance space travel requires 15-plus years of shelf life,” says Contractor. “The way we are working on it is, all the carbs, proteins and macro and micro nutrients are in powder form. We take moisture out, and in that form it will last maybe 30 years.”

Pizza is an obvious candidate for 3D printing because it can be printed in distinct layers, so it only requires the print head to extrude one substance at a time. Contractor’s “pizza printer” is still at the conceptual stage, and he will begin building it within two weeks. It works by first “printing” a layer of dough, which is baked at the same time it’s printed, by a heated plate at the bottom of the printer. Then it lays down a tomato base, “which is also stored in a powdered form, and then mixed with water and oil,” says Contractor.

Finally, the pizza is topped with the delicious-sounding “protein layer,” which could come from any source, including animals, milk or plants.

The prototype for Contractor’s pizza printer (captured in a video, above) which helped him earn a grant from NASA, was a simple chocolate printer. It’s not much to look at, nor is it the first of its kind, but at least it’s a proof of concept.

Replacing cookbooks with open-source recipes

SMRC’s prototype 3D food printer will be based on open-source hardware from the RepRap project.RepRap

Remember grandma’s treasure box of recipes written in pencil on yellowing note cards? In the future, we’ll all be able to trade recipes directly, as software. Each recipe will be a set of instructions that tells the printer which cartridge of powder to mix with which liquids, and at what rate and how it should be sprayed, one layer at time.

This will be possible because Contractor plans to keep the software portion of his 3D printer entirely open-source, so that anyone can look at its code, take it apart, understand it, and tweak recipes to fit. It would of course be possible for people to trade recipes even if this printer were proprietary—imagine something like an app store, but for recipes—but Contractor believes that by keeping his software open source, it will be even more likely that people will find creative uses for his hardware. His prototype 3D food printer also happens to be based on a piece of open-source hardware, the second-generation RepRap 3D printer.

“One of the major advantage of a 3D printer is that it provides personalized nutrition,” says Contractor. “If you’re male, female, someone is sick—they all have different dietary needs. If you can program your needs into a 3D printer, it can print exactly the nutrients that person requires.”

Replacing farms with sources of environmentally-appropriate calories

2032: Delicious Uncle Sam’s Meal Cubes are laser-sintered from granulated mealworms; part of this healthy breakfast.TNO Research

Contractor is agnostic about the source of the food-based powders his system uses. One vision of how 3D printing could make it possible to turn just about any food-like starting material into an edible meal was outlined by TNO Research, the think tank of TNO, a Dutch holding company that owns a number of technology firms.

In TNO’s vision of a future of 3D printed meals, “alternative ingredients” for food include:

- algae

- duckweed

- grass

- lupine seeds

- beet leafs

- insects

From astronauts to emerging markets

While Contractor and his team are initially focusing on applications for long-distance space travel, his eventual goal is to turn his system for 3D printing food into a design that can be licensed to someone who wants to turn it into a business. His company has been “quite successful in doing that in the past,” and has created both a gadget that uses microwaves to evaluate the structural integrity of aircraft panels and a kind of metal screw that coats itself with protective sealant once it’s drilled into a sheet of metal.

Since Contractor’s 3D food printer doesn’t even exist in prototype form, it’s too early to address questions of cost or the healthiness (or not) of the food it produces. But let’s hope the algae and cricket pizza turns out to be tastier than it sounds.

Related Links:

Personal comment:

It looks like cats and dogs are already eating "rapid prototyped" food --from what I see on the pictures here-- and are a step forward in the future from us! ;)

But would it be given to AdriÓ Ferran, it could start to look and taste like something!

But we could also put this in perspective with the recommendation from UN (Food & Agriculture) that humanity should eat more insects in the future, both because it needs less energy and produces less carbon dioxide to produce 1kg of insects (2kg of food produce 1 kg of insects while 20kg produce 1kg of meat...) and because they provide good and healthy nutriments. As many people still don't like to eat insects due to their aspect, turn them into powder and print them might be an interesting way.

Wednesday, January 30. 2013

Mini(Print)-me out of my own garbage?

Note: I'm joining here two posts that hit the blogs recently. The FilaBot 3d printer that print from garbage and the sort of narcissic-souvenir 3d photo booth from Omote 3d. Will it become possible to 3d print snapshots of ouselves, our houses, even our food with our own garbage (including therefore food garbage...)? Which would be a decent way to recycle trash (best way actually might be distant heating).

-----

Of the many fictionalized, futuristic innovations shown in the Back to the Future movies, one of the most beneficial belonged to the DeLorean at the center of it all, and I don’t mean the ability to time travel. Rather, if even regular engines could run on garbage, we’d solve the issues of fuel availability and waste disposal in one fell swoop. That’s why it’s nice to see that this concept has come into existence right at the upswing of the 3D printing phenomenon.

FilaBot is a desktop device that breaks down various types of plastics and processes them into filament that you can use for your home 3D printer. That includes your botched 3D printed experiments, so you won’t be wasting filament when you’re testing out a design.

Their Kickstarter campaign, which closed in early 2012, clocked three times its goal, and should prove to be a great accompanying device for home 3D printers like MakerBot. Founder Tyler McNaney plans to create a whole range of products that offer this functionality, some with great potential for customization.

FilaBot is a welcome arrival to a burgeoning world of creativity that threatens to create an immense amount of waste, something that we’re already pretty good at rapidly creating in large volumes. Now, instead of adding to the garbage pile, we can process some of our existing waste into something useful… well, depending what you’ll be designing and fabricating.

[via The Guardian]

----------

Un photomaton d’un nouveau genre vient de voir le jour à Tokyo: il crée une figurine à l'image du modèle. Complètement mégalo mais idéal pour les amateurs de petits soldats de plomb.

A priori ce n’est qu’un gadget de plus pour consommateurs en mal d’ego trip. Mais les figurines créées par Omote 3D, photomaton installé pour quelques semaines à Omotesando, coeur de la consommation de luxe tokyoïte, prouvent que l’impression 3D est en passe de devenir un produit grand public.

Le Pop up studio ouvrira dans une galerie de Tokyo le 24 novembre prochain. On pourra s'y faire tirer le portrait, à la façon d’un photomaton - mais avec l'aide d'un photographe professionnel. Le portrait sera ensuite scanné et à partir des données enregistrées, et une figurine à l'image du client verra le jour. La machine, appelée Omote 3D, propose donc de transformer le chaland en petit soldat de plomb – mais en plastique et sans fusil. Pour 200 euros (la figurine de dix centimètres), le laboratoire Party, Rhizomatiks et Engine Film livrent l’objet, qu'il s’agit ensuite de colorer soi-même.

Les prix sont encore assez élevés mais la technique en est à ses prémices : de 21 000 yens (200 euros) pour une figurine de 10 cm à 42 000 yens (400 euros) pour la plus grande version de 20 centimètres.

En juin dernier, durant les Designer's day, les Français de Sismo proposaient déjà aux visiteurs de modeliser leurs visages et les faisaient surgir de pièce de monnaie. Le studio Sismo édite également des reproductions de crânes, vanités des temps futures, contre quelques milliers d'euros.

Related Links:

Personal comment:

An interesting twist with 3d printing: to use it as a way to recycle our old PET bottles or plastic trash (and by extension any trash, including organic waste to 3d print food?). And a way to potentially produce strange self consumption portrait.

Friday, March 11. 2011

3D Candy Printing: An Interview with Designer Marcelo Coelho

Three-dimensional printers are getting a lot of hype at the moment. In February, MakerBot Industries started shipping its Thing-o-Matic desktop 3D printer, which, at just $1,225, "democratizes" 3D printing, allowing you to "live in the cutting-edge personal manufacturing future of tomorrow!" The same month, the typically restrained Economist headlined a story "Print me a Stradivarius: How a New Manufacturing Technology Will Change the World." Business Insider even called it "The Next Trillion Dollar Industry."

The idea, for those of you who aren't familiar with it, is pretty simple. You create a 3D design on your computer or download a premade blueprint. Then you press print. Your printer squirts materials out of a nozzle that is sort of like an ink jet printhead, and builds up the object gradually, one layer at a time. When it finishes and the object has cooled, you have a new thing. Not a picture of a thing, but the thing itself.

And people are already using the technology to print all sorts of things—pesticide-free plastic bug repellents, new ears, and videogame cars.

They're also printing food.

For example, both the BBC and the CBC have recently reported on the 3D food printer being tested at Cornell University's Computational Synthesis Lab (CCSL). So far, the team there have created miniature space shuttles made out of ground scallops and melted cheese, chocolate letters, and cubes of raw turkey and celery, mixed with hydrocolloids to create a gel.

Meanwhile, across the pond, tech company Bits from Bytes are collaborating with the University of the West of England to try to print mashed potatoes.

The somewhat underwhelming aesthetic results of these experiments do not discourage 3D food printing's proponents, who dream of the chance to rapidly prototype and tweak new flavor and texture combinations, the ability to digitally control nutrient intake and ensure food safety, and the possibility that, one day, your mom will be able to send you a slice of her apple pie over email. And, undoubtedly, if 3D food printers become as ubiquitous as personal computers, it will utterly change the way we think about food, as well as reshape the built environment, from kitchen design to supermarket layout.

To find out more about how these 3D food printers actually work and how they might change our lives, I talked to Marcelo Coelho, an industrial designer with MIT Media Lab's Fluid Interfaces Group. Last year, he and Amit Zoran released a series of concept drawings for a digital gastronomy project they called Cornucopia. Now, Coelho has created a prototype digital chocolatier—a personal, 3D candy printer. Our conversation is below.

GOOD: The last time we talked, in February 2010, you had come up with these concept drawings. Can you talk through the process of turning them into a working prototype.

Coelho: We started by looking at what was possible using real world technology. The biggest challenge in making a 3D food printer is controlling the food. We experimented with different types of ingredients and with different kinds of valve design. I’m definitely not a food engineer, so I went through a whole process of getting a better sense of the properties of the foodstuffs that I was working with and what sorts of devices have been invented to work with each of them on the industrial scale. I looked at a lot of books about the design of machines for food factories.

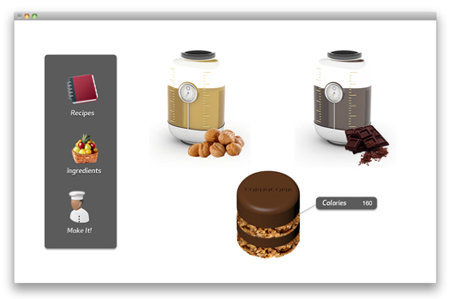

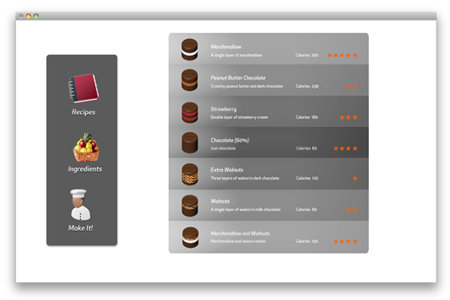

Eventually, I arrived at a prototype that combined chocolate and nuts in different amounts. The machine has a little carousel with two different types of chocolate and two different types of nuts—just regular chocolate, white chocolate, almonds, and walnuts, bought from a store. I designed a graphical user interface so you can just click on the food that you want and it gets added to the design. So, for example, you might click on the chocolate and a tiny little bit of chocolate gets added to that candy design. Then you might do a layer of nuts, and you keep selecting the amount and the arrangement of those layers. When you're done, you just hit the candy button, and the machine goes through the process of printing it out.

I really tried to show what happened while the machine was making the candy, so as the machine starts to extrude the chocolate and the walnuts, the graphic representation of the candy on the user interface also shows what’s happening—you see the layers appearing on the virtual candy as it's appearing on the physical candy. I think that's an important part of the process, so that people could see how the food is coming to be what it is.

GOOD: So do you actually have to design the whole candy before it even starts printing?

Coelho: No, you can do as much as you want, and then just hit the candy button and whatever you've created so far will get printed.

GOOD: That's good, because I can easily see how you would design something that looks good and then as it prints, realize, you know what, I want a little bit more chocolate…

Coelho: Absolutely. So you could print two layers of chocolate, stop and then put a marshmellow in the middle of this thing by hand and then print some more layers of chocolate and nuts. I think creating this symbiosis between the machine and the people using it is very important.

GOOD: When other people tested the prototype and printed candy for themselves, did they do things that you weren’t expecting with it?

Coelho: I think the most surprising things was how much people liked their candies. They tasted really good. I was a bit surprised. I don’t know why, because we used good chocolate and real nuts and we were just depositing them in different ways, but I thought the candy was going to taste funny. I also think people were just fascinated by the idea of making candy. There’s a lot of creative space in candy design.

GOOD: One practical question: How do you keep the chocolate at the right temperature so it can extrude? Do you add something to the mix, or is it just melted chocolate?

Coelho: It’s melted chocolate, and there’s a hidden film that goes in the chocolate tube with a heating element and a thermostat, so you can heat it and then keep it at a steady temperature. The heating is more localized at the bottom, near the valve.

GOOD: How do you top it up?

Coelho: You just buy a bag of chocolate chips from the grocery store and tip it into the tube.

GOOD: Given that this is a prototype, what are some of the things you would need to refine before production?

Coelho: There are a few things. Right now, it takes about a minute for the candy to harden. We could speed that up by putting the entire machine inside a little chamber, for better temperature control. Another thing is that over time the valves start getting clogged and you have to take the whole thing apart. I would like it to be super easy to detach the valves and just pop them into the dishwasher. But each of these things is a separate and really hard design challenge.

It does work pretty well, but the next step is to build it so it works reliably for a long time and also combine this printing carousel with a plotter, so that we can not only control the type and amount of food that is dispensed, but also create lines with it.

GOOD: In some ways, what a device like this is doing is putting the tools that are already in a factory into people’s houses. What’s the interest and value, for you, in taking these industrial food processing techniques and building them at the scale of the home kitchen.

Coelho: There are several layers to it, but I think it all comes down to idea of giving people more information. I think of information in two different ways: one is just learning about what you’re eating and the second is actually becoming a part of the information design process or part of the food production process.

So you’re right: There’s plenty of stuff at the grocery store that is made in a factory using these kinds of extruding devices at an industrial scale. But most people have no idea what goes in to making them. I wanted to create a machine that would let people have more information about what they're eating and how it's made, and then, on top of that, also be able to make choices and design their own food.

GOOD: I could see some people looking at this and saying, "Why not just eat a bar of chocolate and some nuts? What’s the point in going through this whole 3D printing process?"

Coelho: That’s a good question, and it goes back to where this project started. I noticed that every aspect of the design world has been really affected by 3D printers, and people spend a lot of time talking about the idea of these machines being in everyone’s homes one day and how it will revolutionize everything. Those conversations made me realize that right now, the only thing that most people really design or create in their own homes is the food they cook. For example, my parents never make anything ever—but they cook frequently, if not every day. So I thought that food would be a really interesting place to explore the potential of domestic digital design.

GOOD: So a 3D food printer is actually a vehicle for people to take something that they’re familiar with doing, which is cooking, and introduce them to design thinking.

Coelho: Exactly. I think it also unleashes an infinite amount of possibilities. When you think about the kinds of things you can do on your computer in terms of design—simple things, like a Photoshop blur filter, for instance—it makes you wonder what a blur filter for food would be? What would it do and taste like? I think there's a really exciting opportunity to give people the same sort of one-button design tools they have on their computer, but for food.

GOOD: Did you build this prototype just to experiment with the ideas, or are you interested in developing it into something I could actually buy at Williams Sonoma?

Coelho: I would love to take it into production! I actually think designers have a big responsibility to explain what's possible and what's not possible, as well as just coming up with creative ideas. When Amit and I put out our concept designs this time last year, people wrote about them as if they were real, and that was really frustrating to me. I had never created concept renderings before, and it made me realize the responsibility of creating a fantastically realistic image—people look at it and think it exists. I think it's important to make that distinction between concept and reality clear because it affects society's reaction to new technologies, as well as what kind of research gets funded and what doesn’t.

Anyway, that's the part of the design process that I really like, the part where you actually try making it and see what works and what doesn't.

Images: (1) Digital chocolatier, Marcelo Coelho; (2) Scallop and cheese spaceshuttle, Cornell University/French Culinary Institute, via the CBC; (3) Turkey and celery square, photo by Dan Cohen, via the BBC; (4) Printed mashed potatoes, via Fabbaloo; (5) Digital chocolatier, Marcelo Coelho; (6) Graphical User Interface, Marcelo Coelho; (7) Graphical User Interface, Marcelo Coelho; (8) Digital chocolatier, Marcelo Coelho; (9) Digital chocolatier, Marcelo Coelho; (10) Concept drawing for a digital fabricator, Marcelo Coelho.

Monday, January 18. 2010

MIT's Food Printer: The Greenest Way To Cook?

Images from MIT Fluid Interface Group

Everyone is talking about local food, farmers markets and like, cooking? Who has time for that? And really, is Michael Pollan serious with his Rule #2- "Don't eat anything your great-grandmother wouldn't recognize as food." Why bother even having an MIT if you are going to think that way?

Make shows us how Marcelo Coelho and Amit Zoran of the Fluid Interfaces Group at MIT propose a much greener, more efficient, waste-free process: Print out your dinner.

Cornucopia is a concept design for a personal food factory that brings the versatility of the digital world to the realm of cooking. In essence, it is a three dimensional printer for food, which works by storing, precisely mixing, depositing and cooking layers of ingredients.

Cornucopia's cooking process starts with an array of food canisters, which refrigerate and store a user's favorite ingredients. These are piped into a mixer and extruder head that can accurately deposit elaborate combinations of food. While the deposition takes place, the food is heated or cooled by Cornucopia's chamber or the heating and cooling tubes located on the printing head.

Just imagine the impact this would have. Real food rots. It has peels. Half of it is wasted. The whole infrastructure of food stores with their refrigerated cases becomes unnecessary. And imagine, no more pesky farmers markets occupying valuable parking lots. This is truly green.

More at MIT's Fluid Interfaces Group

-----

Via Treehugger

Personal comment:

Looks like a future hybrid between old food artifacts dedicated to the conquest of space (pills and paste in tubes tasting like food) and 3d model printing. Maybe will be go toward a new type of room in our living spaces. Instead of the kitchen, we will have the printing room (where we'll print food, objects and magazines...)

fabric | rblg

This blog is the survey website of fabric | ch - studio for architecture, interaction and research.

We curate and reblog articles, researches, writings, exhibitions and projects that we notice and find interesting during our everyday practice and readings.

Most articles concern the intertwined fields of architecture, territory, art, interaction design, thinking and science. From time to time, we also publish documentation about our own work and research, immersed among these related resources and inspirations.

This website is used by fabric | ch as archive, references and resources. It is shared with all those interested in the same topics as we are, in the hope that they will also find valuable references and content in it.

Quicksearch

Categories

Calendar

|

|

December '25 | |||||

| Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat | Sun |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| 29 | 30 | 31 | ||||