Monday, April 11. 2011

-----

by Cord Jefferson

This is going to sound sort of obvious, but here we go: A study from University College London published this week in Current Biology has discovered that there are actually differences in the brains of liberals and conservatives. Specifically, liberals' brains tend to be bigger in the area that deals with processing complex ideas and situations, while conservatives' brains are bigger in the area that processes fear.

According to the report: "We found that greater liberalism was associated with increased gray matter volume in the anterior cingulate cortex, whereas greater conservatism was associated with increased volume of the right amygdala."

People with larger amygdalae respond to perceived threats with more aggression and "are more sensitive to threatening facial expressions." The anterior cingulate cortex, however, "monitors uncertainty and conflict." "Thus," says the report, "it is conceivable that individuals with a larger ACC have a higher capacity to tolerate uncertainty and conflicts, allowing them to accept more liberal views."

The London researchers say they're unsure whether the brain's structure causes political views or is the effect of them. Regardless, this puts the "Obama's a Muslim socialist" fearmongering at Tea Party rallies into a whole new light.

photo (cc) via Flickr user Jon Olav

Friday, April 01. 2011

Via OWNI

-----

by Andréa Fradin

“Qui suis-je ? Où vais-je ? Dans quelle étagère ?” Pour certains spécialistes des neurosciences, il semblerait que cette quête de sens, ainsi que toutes nos angoisses existentielles, traîneraient du côté du rayon “cerveau”. Et il en serait de même pour LA question: et Dieu, dans tout ça ?

Voilà une dizaine d’années qu’un petit nombre de chercheurs, principalement américains et canadiens, recherchent activement les manifestations du Grand Horloger, et plus généralement la source de la spiritualité, dans les méandres cérébraux. La pratique, baptisée “neurothéologie”, restée aujourd’hui à la marge, est souvent présentée comme un domaine d’études un peu curieux, à la légitimité faiblarde. Pourtant, ils ne sont pas tous à chercher la preuve de l’existence (ou pas, d’ailleurs) de Dieu dans le fatras synaptique. Il est vrai que certains n’hésitent pas à clamer haut et fort avoir localisé une zone extatique cérébrale, sorte de bouton-pressoir activateur de foi.

D’autres en revanche, plus modérés, rétorquent que là n’est pas la question. Ni démonstrateurs en odeur de sainteté, ni abatteurs de divinités, ces chercheurs tentent d’observer une réalité vécue et exprimée: celle des états de conscience modifiés, des expériences dites “mystiques”, de la méditation, ou bien encore de la sensation d’unicité avec le monde. Expliquer la spiritualité en scrutant la cervelle humaine: difficile d’envisager entreprise plus périlleuse, tant les réticences en provenance des deux bords, science et religion, viennent impacter et questionner les conditions expérimentales des “neurothéologues”.

Neuro-localisation de Dieu

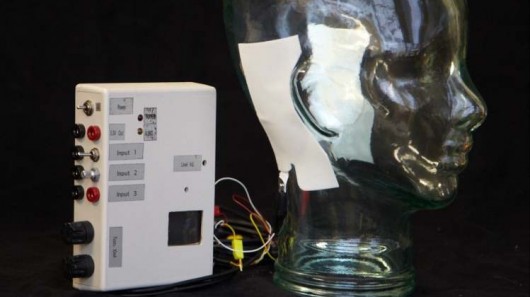

Le "casque de Dieu" du chercheur Michaël Persinger (extrait de la série "Through the Wormhole" de Science Channel)

Avec son “Helmet God” (“casque de Dieu”), Michael Persinger [ENG] fait figure de précurseur dans le domaine de la neurothéologie.

L’objectif de ce chercheur américain est de reproduire l’expérience mystique en stimulant certaines zones du cerveau, comme le lobe temporal -qui joue un rôle déterminant dans la production des émotions-, grâce à des ondes magnétiques émises par son fameux casque jaune.

Si l’electro-encéphalogramme s’affole au cours de chaque expérience, les retours des différents cobayes, eux, sont loin d’être univoques: quand certains affirment avoir l’impression qu’une “entité” était auprès d’eux, d’autres, en revanche, disent tout simplement ne rien avoir ressenti.

Avant Persinger, un chercheur de l’université de San Diego, Vilayanur Ramachandran, cherchait déjà une base neurologique aux manifestations spirituelles. Ses travaux portaient sur certaines formes d’épilepsie affectant ce même lobe temporal et pouvant entrainer des délires mystiques intenses chez les individus en crise. Une observation qui a valu le titre de “module de Dieu” à cette région du cerveau, dans laquelle on retrouve l’hippocampe, ou l’amygdale.

Pour Carol Albright, auteur de nombreux ouvrages sur la neurotheologie et rédactrice au magazine Zygon: Journal of Religion and Science, l’approche matérialiste de ces deux chercheurs, qui tentent de prouver “que toute expérience ou foi religieuses sont une aberration ou artefact”, est une conception “limitée de ce que comprend la religion”. Elle explique à OWNI:

Personnellement, je pense que l’expérience religieuse est bien plus multiple que ce que prétendent ou rapportent de tels scientifiques. Elle peut inclure des expériences mystiques de la présence de Dieu, mais elle comporte aussi une doctrine intellectuelle, une participation au rituel, et une orientation générale de la personnalité, entre autres paramètres.

Autrement dit, elle ne se limite pas à l’extase mystique, produit de l’expérience spirituelle; elle inclue aussi des éléments de contexte qui viennent bien en amont de cette manifestation, et qui dépassent le seul cadre du cerveau. Bien entendu, tempère Carol Albright, chaque affect humain a une résonance cérébrale, mais réduire la spiritualité à cette seule réalité, et plus encore, la percevoir comme seule raison à Dieu, est un raccourci simpliste.

Au-delà du matérialisme réductionniste

De là à associer l’intégralité de la neuroscience à une approche matérialiste du religieux, il n’y a qu’un pas. Pourtant, souligne encore l’analyste américaine, certains travaux se démarquent par une approche moins reductionniste.

Les américains Andrew Newberg et Eugene d’Aquili, auteurs du succès de librairie Why God Won’t Go Away: Brain Science and the Biology of Belief et initiateurs du terme “neurothéologie”, le canadien Mario Beauregard de l’université d’Ontario, cherchent moins à neuro-localiser Dieu qu’à observer la traduction cérébrale d’états de consciences modifiés. “A chaque fois, on n’a aucune idée de ce qu’on va trouver”, confie un assistant de Mario Beauregard à la caméra venue filmer les expériences de cette équipe de neurobiologistes, pour le documentaire Le Cerveau mystique, réalisé en 2006 (l’intégralité à voir ci-dessous).

En étudiant les états méditatifs de nonnes carmélites, ils tentent de comprendre le “cerveau spirituel”. Mais là encore, de bout en bout de l’expérimentation, la tache est difficile: convaincre les religieuses, repérer le moment extatique sans pouvoir interrompre la méditation, et surtout, interpréter les données sans savoir précisément qu’y chercher. La neurothéologie avance donc à tâtons. Mais dans une visée moins philosophique que pratique: pour ces chercheurs, l’objectif est d’augmenter le bien-être des individus, bien plus que de jouer à la devinette ontologique.

///

En ce sens, de nombreux neurothéologiens ont concentré leurs efforts sur l’étude de la méditation, afin de comprendre sa mécanique mais aussi ses effets sur le cerveau et le corps.

L’un des premiers à avoir aborder la thématique est le professeur Richard Davidson, qui s’est penché sur des moines bouddhistes ayant consacré plusieurs dizaines de milliers d’heures à la méditation. “Étudier leur cerveau, explique-t-il dans Le Cerveau Mystique, est un peu comme observer des maîtres d’échecs.”

Et il semblerait que l’activité cérébrale d’une personne entrée en méditation varie assez considérablement de celle d’un individu lambda: “il y a un changement spectaculaire entre les novices et les pratiquants”, explique Antoine Lutz, qui travaille en étroite collaboration avec les moines, parmi lesquels figure l’interprète français du Dalaï-Lama, Matthieu Ricard, très porté sur les avancées de la neuroscience.

Et il n’est pas le seul: le guide spirituel du mouvement est lui-même très investi dans le domaine. Le Dalaï-Lama est en effet co-fondateur et président honoraire du Mind and Life Institute, qui vise à “construire une compréhension scientifique de l’esprit pour réduire la souffrance et promouvoir le bien-être”.

Un engagement qui n’a rien d’anodin, car, comme le souligne un moine cistercien invité d’un congrès du Mind and Life:

Depuis mille ans, la religion et la science se sautent à la gorge dès qu’elles en ont l’occasion

Une façon de rétablir la trêve, même si des irréductibles refusent d’abandonner le front. “Il y a des “fondamentalistes” de chaque côté du débat -ceux qui ne jurent que par la science ou à l’inverse, seulement par la religion-, qui cherchent à saper l’autre clan”, explique Carol Albright. Résidente de Chicago, elle explique comment cinq écoles de théologie cohabitent avec l’approche scientifique:

Je vis dans le quartier de Hyde Park, à Chicago, où se trouvent l’Université de Chicago, ainsi que cinq écoles de théologie – Catholique Romaine, Luthérienne, Unitarienne, et deux autres se rapprochant du Calvinisme… Ajouté à cela, l’Université de Chicago a une Divinity School qui défend une approche très universitaire. J’ai des amis de chacune de ces confessions, qui travaillent à comprendre l’interaction de la science et de la religion. Ils ne cherchent pas à nier les conclusions scientifiques, mais bien plus à les intégrer à leur pensée, afin de mieux évaluer l’état de la connaissance de nos jours.

Qu’en est-il pour la France ?

Il semblerait qu’une telle approche soit moins entravée par une réserve pieuse que par l’ostracisme de la communauté scientifique. Doctorant en neurosciences cognitives et à l’origine d’Arthemoc, première association scientifique se concentrant sur l’étude des états modifiés de conscience en France, Guillaume Dumas raconte:

En France, on est vraiment à la traîne sur tous ces sujets; il est difficile de sortir des sentiers battus. Dès qu’on évoque la religion dans des thèmes de recherche, on n’est pas loin d’être insultés. Cela m’est même arrivé dans une présentation pour Arthemoc alors que j’évoquais juste les effets de la méditation. Il suffit de prendre le cas de Francisco Varela pour comprendre la situation française. C’était un chercheur brillant, fondateur du Mind and Life Institute, mais dont un article sur la méditation lui a presque coûté une accréditation lui permettant d’accéder au poste de directeur de recherche.

Difficilement surmontable par les neuro-scientifiques, ce déni de légitimité alimente, ironie suprême, la fuite des cerveaux outre-Atlantique. Comme le constate, amer, Guillaume Dumas:

La seule solution est de partir aux États-Unis. C’est ce qu’a fait Antoine Lutz, un ancien doctorant de Varela qui souhaitait justement étudier la méditation en neuro-imagerie.

Thursday, March 17. 2011

Via MIT Technology Review

-----

Device maps the chemistry of the whole brain in moving animals.

By Katherine Bourzac++

|

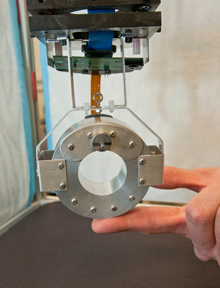

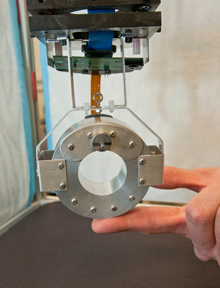

Wearable PET: A rat’s head fits in the circular opening of this device, which is surrounded by miniaturized detectors and electronics.

Credit: Brookhaven National Laboratory |

A tiny wearable scanner has been used to track chemical activity in the brains of unrestrained animals for the first time. By revealing neurological circuitry as the subjects perform normal tasks, researchers say, the technology could greatly broaden the understanding of learning, addiction, depression, and other conditions.

The device was designed to be used with rats—the main animal model used by behavioral neuroscientists. But the researchers who developed the device, at Brookhaven National Laboratory, say it would be straightforward to engineer a similar device for people.

Positron emission tomography, or PET, is already broadly used in neuroscience research and in clinical treatment. It allows researchers to track the location of radioactively labeled neurotransmitters (the chemicals that carry signals between neurons) or drugs within the brain. Images of the way neurotransmitters and drugs move through the brain can reveal the processes that underpin normal behavior such as learning as well as pathologies including addiction. PET has been used to map drug-binding sites in the brains of addicts and healthy people, and to study how those sites change over time and with therapy.

A conventional PET scanner is so large that these studies have to be performed with the subject lying inside a large tube. Large photomultiplier tubes amplify signals from gamma rays emitted by labeled chemicals in the brain. The signals then pass through a desk-sized rack of electronics that process them and map them to a particular region of the brain. To get good readings during animal studies, the subjects are typically anaesthetized or restrained. What's being measured is not normal waking behavior.

"We have very limited data about what brains do in the real world," says Paul Glimcher, professor of neuroscience, economics, and psychology at New York University. Glimcher was not involved with the work.

The new portable scanner is designed to provide the same information about brain chemistry while an animal behaves naturally. It is small and lightweight enough that a rat can carry it around on its head. "[The rat] can move freely, interact with other animals, and at the same time we can make a 3-D map of, for example, dopamine receptors throughout the brain," says David Schlyer, a senior scientist at Brookhaven who led the work.

Schlyer's group worked for years to engineer a miniature PET scanner that could be worn by a moving subject. The device consists of a metal ring hanging from a support structure that helps support its weight and allows the rat to move around. The rat's head goes inside the ring, which contains both detectors and electronics.

The key to miniaturizing the device, Schlyer says, was integrating all the electronics for each detector in the ring on a single, specialized chip. An avalanche photodiode also replaces the large photomultiplier tubes of conventional PET, amplifying the signals emitted by the labeled chemicals in the brain. "The rats take about an hour to acclimate, then begin behaving normally," says Schlyer. The Brookhaven device is described this week in the journal Nature Methods.

The Brookhaven group used the scanner to map the dopamine receptors throughout the entire brains of of moving rats for the first time. Other groups, including Glimcher's, have previously used invasive probes to study dopamine levels in cubic-millimeter-sized portions of the brain in unrestrained animals, but have not been able to look at the entire brain.

Glimcher describes one of several experiments that could be done with the portable device. Researchers know that addicts who have successfully completed rehab are at great risk of relapse if they visit the places they associate with the drug, probably because their brain has been chemically rewired to respond to these associations. Glimcher imagines studies in rats that map brain chemistry when the animals are allowed to decide whether or not to take a drug, and when they wander into a location they have learned to associate with the drug.

"We don't really understand that well how circuits in [different parts of the brain] interact in addiction," says Glimcher. "To even get to a place where I can give you a clinical hypothesis, we have got to get more basic information. This is the breakthrough that could make that possible."

PET is not as broadly used in studies involving people as other neuroimaging methods because of the small but significant exposure to radiation that's necessary. Still, the Brookhaven researchers say it would be possible to make a wearable PET scanner that fits inside something resembling a football helmet. Joseph Huston, chair of the Center for Behavioral Neurosciences at the University of Düsseldorf, says the Brookhaven group has done "an incredible service" to the neuroscience community in developing the device. "The rat is the most important model for the brain—everything basic [we know] about learning, feeding, fear, sex, is based on work in the rat."

Schlyer says his group has talked with a few companies about licensing a commercial version of the device. But for now, they are mainly planning further behavioral studies in their lab. Mapping dopamine in waking animals could provide insights into a wide range of normal and pathological conditions such as the movement problems associated with Parkinson's disease. But dopamine is just one of the many brain chemicals the group can map. Schlyer says they will also study the sexual behavior of rats.

The group is also working on another instrument that combines PET with magnetic resonance imaging to provide richer information about tissue structure and function. They will start a clinical trial of this device in breast cancer patients next month.

Copyright Technology Review 2011.

-----

You can also read on the same subject: An On-Off Switch for Anxiety (MIT Tech Review as well)

Personal comment:

I blog this article from the MIT because I more and more believe that researches in neuroscience will have a huge incidence in the future on how we understand the way humans (and animals) and possibly artificial intelligences interact with each other, with their environment, with situations, etc. and how these behaviours can trigger specific patterns in the brain (neural, chemical, electric activities and hormones secretions, etc.) and/or in the body, which in return certainly condition what we "feel" about this situation. This would also mean that a "feeling" is somehow also very material (brain pattern, hormones, etc.)

So to say, I believe that spatial conditions in architecture or environments triggers certain brain conditions that could be in fact the direct "way" we experience this environment (comfortable, agressive, "nice", "ugly", hot, cold, ...).

One step further and we could possibly sometimes replace the space itself (or its experience) by it's brain pattern (drugs?) triggering the same feeling.

For my part, I will keep an eye full of curiosity on the results of researches in neurosciences ...

Friday, August 27. 2010

Via Gizma

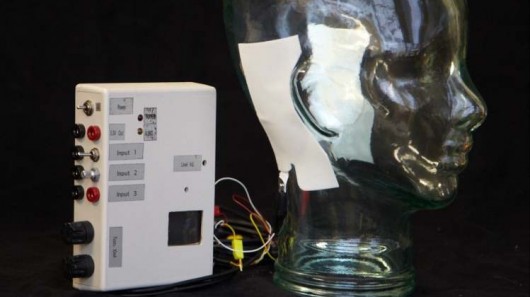

There are airplanes and swimming pools that give prospective astronauts a taste of what a zero-gravity environment will feel like, but the sensations that they will feel upon returning from such an environment are also important to simulate. Astronauts coming back to Earth’s gravity often experience disturbances in their vision and neurological function, to the point that they can have trouble walking, keeping their balance, or even safely landing their spacecraft. By utilizing a Galvanic vestibular stimulation (GVS) system, however, scientists can give them a sneak peek of what to expect, so they can better compensate for it when it happens in the field.

The system was developed by Dr. Steven Moore of the National Space Biomedical Research Institute (NSBRI). It consists of a small box, which sends a 5 milliamp current to electrodes placed behind the subjects’ ears. Those electrodes deliver electricity through the skin to the vestibular nerve, which in turn sends signals to the brain that result in sensorimotor disturbances. Because the box is portable, subjects can carry it with them while attempting to walk – no doubt a big hit at the NSBRI’s office parties.

Moore tried his system out on 12 test subjects at the NASA Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California. Each subject flew 16 simulated shuttle landings, half of those landings with the GVS and half without. He compared the results to data collected from over 100 shuttle landings. Subjects using the GVS, he concluded, experienced disturbances similar to those experienced by shuttle pilots on actual flights.

Without the GVS, subjects tended to land the shuttle at a simulated speed of 204 knots, which is right on target. With the GVS, the average speed increased to around 210 knots, which is at the upper limit of the safety zone. Likewise, GVS-using subjects also had more difficulty performing a routine landing approach braking maneuver that required them to bring the craft from a 20-degree glideslope angle to a 1.5-degree angle. This is a point in real shuttle flights at which pilots often experience sensorimotor disturbances.

Moore stated that his system could be used as an analog for other space vehicles and operations, and that it could even be used to prepare people with vestibular disorders for the effects following surgery. The NSBRI research team is now trying to determine if people can adapt to the effects of the GVS over multiple sessions.

Monday, March 29. 2010

Via Jargon, etc.

-----

by jared.langevin@gmail.com (Jared Langevin)

New Scientist published an interesting article this week about the influence of the body's positioning in space on one's thought processes. According to recent research, space and the body are actually much more connected to the mind than has been traditionally accepted. The article cites a study by researchers at the University of Melbourne in Parkville, Australia which found that the eye movements of 12 right handed male subjects could be used to predict the size of each in a series of numbers that the participants were asked to generate; left and downwards meant a smaller number than the previous one, while up and to the right meant a larger number. A separate study at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, asked 24 students to move marbles from a box on a higher shelf to one on a lower shelf while answering a neutral question, such as "tell me what happened yesterday". The resulted showed that the subjects were more likely to talk of positive events when moving marbles upwards, and negative events when moving them downwards.

Read more about this here.

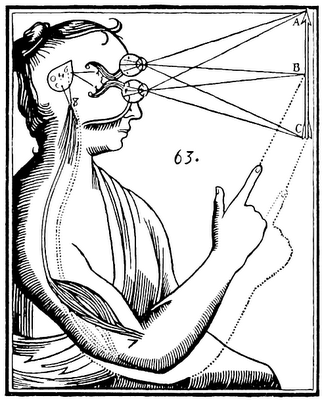

The notion that our bodies' direct physical relationship to space can influence thoughts is exciting, and reopens arguments against the ontological distinction between mind and body that is most commonly identified with Descartes, as well as associated questions of physical determinism vs. indeterminism . Going further, I suspect that less overt interactions between the body and its surrounding environment could be also included in this discussion, such as the psychological perceptions of temperature, humidity, and other similarly invisible environmental characteristics. The New Scientist article also references a 2008 study from the Rotman School of Management in Toronto that shows that social exclusion has the effect of making people feel colder. The issue of causality abounds here: if social exclusion or inclusion affects a person's temperature perception, would variant temperatures also be able to yield varying types of associated social behavior? Could we extend this discussion to the somewhat perverse notion that a carefully controlled interior environment is actually a form of mind control? ...

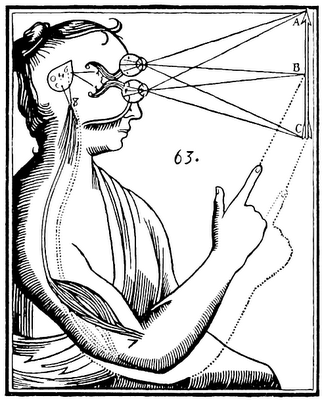

A drawing from René Decartes' Meditations on First Philosophy illustrates his

belief that the immaterial (mind, soul, "animal spirit") and material (body)

interact through the pineal gland in the center of the brain.

Wednesday, July 22. 2009

Monkey's can quickly adapt to neural prostheses.

By Emily Singer

A new study of neural prostheses in monkeys suggests that learning to control a robotic arm with the power of thought may happen more naturally than scientists had expected. Jose Carmena and Karunesh Ganguly at the University of California, Berkeley (UCB), found that the animals create a mental map of the device, much as we do when learning to swim or swing a tennis racket.

A number of labs have already shown that monkeys--and in a few cases, humans--with electrodes implanted into their brains can learn to control a computer cursor or robotic arm. To train the subjects, scientists first record the activity in a group of neurons as the monkey moves its real arm (or in the case of a paralyzed human, as the person imagines moving his or her arm). Researchers then analyze the neural activity to develop a decoding algorithm that can translate the pattern of brain-cell firing into an action--say, moving a cursor to a certain point on a computer screen.

In the new study, published today in the journal PLoS Biology, monkeys learned to precisely control a computer cursor over a few days. As the animals became proficient at the task, the researchers identified a specific pattern of neural activity in the brain associated with the movement. "The profound part of our study is that this is all happening with something that is not part of one's own body. We have demonstrated that the brain is able to form a motor memory to control a disembodied device in a way that mirrors how it controls its own body. That has never been shown before," said Carmena in a press release from UCB.

The research also suggests that optimizing the decoders may not be as important as expected. A few weeks after the monkeys learned to control the arm with the original decoder, Carmena and Ganguly introduced a new one, indicated by a different colored cursor. According to the release:

As the monkeys were mastering the second decoder, the researchers would suddenly switch back to the original decoder and saw that the monkeys could immediately perform the task without missing a beat. The ability to switch back and forth between the two decoders shows a level of neural plasticity never before associated with the control of a prosthetic device. "This is a study that says that maybe one day, we can really think of the ultimate neuroprosthetic device that humans can use to perform many different tasks in a more natural way," said Carmena.

-----

Via MIT Technology Review

|