Here's a story you've heard about the Internet: we trade our privacy for services. The idea is that your private information is less valuable to you than it is to the firms that siphon it out of your browser as you navigate the Web. They know what to do with it to turn it into value—for them and for you. This story has taken on mythic proportions, and no wonder, since it has billions of dollars riding on it.

But if it's a bargain, it's a curious, one-sided arrangement. To understand the kind of deal you make with your privacy a hundred times a day, please read and agree with the following:

By reading this agreement, you give Technology Review and its partners the unlimited right to intercept and examine your reading choices from this day forward, to sell the insights gleaned thereby, and to retain that information in perpetuity and supply it without limitation to any third party.

Actually, the text above is not exactly analogous to the terms on which we bargain with every mouse click. To really polish the analogy, I'd have to ask this magazine to hide that text in the margin of one of the back pages. And I'd have to end it with This agreement is subject to change at any time. What we agree to participate in on the Internet isn't a negotiated trade; it's a smorgasbord, and intimate facts of your life (your location, your interests, your friends) are the buffet.

Why do we seem to value privacy so little? In part, it's because we are told to. Facebook has more than once overridden the privacy preferences set by its users, replacing them with new system-wide defaults. Facebook then responds to the inevitable public outcry by restoring something that's like the old system, except slightly less private. And it adds a few more lines to an inexplicably complex privacy dashboard.

Even if you read the fine print, human beings are awful at pricing out the net present value of a decision whose consequences are far in the future. No one would take up smoking if the tumors sprouted with the first puff. Most privacy disclosures don't put us in immediate physical or emotional distress either. But given a large population making a large number of disclosures, harm is inevitable. We've all heard the stories about people who've been fired because they set the wrong privacy flag on that post where they blew off on-the-job steam.

The risks increase as we disclose more, something that the design of our social media conditions us to do. When you start out your life in a new social network, you are rewarded with social reinforcement as your old friends pop up and congratulate you on arriving at the party. Subsequent disclosures generate further rewards, but not always. Some disclosures seem like bombshells to you ("I'm getting a divorce") but produce only virtual cricket chirps from your social network. And yet seemingly insignificant communications ("Does my butt look big in these jeans?") can produce a torrent of responses. Behavioral scientists have a name for this dynamic: "intermittent reinforcement." It's one of the most powerful behavioral training techniques we know about. Give a lab rat a lever that produces a food pellet on demand and he'll only press it when he's hungry. Give him a lever that produces food pellets at random intervals, and he'll keep pressing it forever.

How does society get better at preserving privacy online? As Lawrence Lessig pointed out in his book Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace, there are four possible mechanisms: norms, law, code, and markets.

So far, we've been pretty terrible on all counts. Take norms: our primary normative mechanism for improving privacy decisions is a kind of pious finger-wagging, especially directed at kids. "You spend too much time on those Interwebs!" And yet schools and libraries and parents use network spyware to trap every click, status update, and IM from kids, in the name of protecting them from other adults. In other words: your privacy is infinitely valuable, unless I'm violating it. (Oh, and if you do anything to get around our network surveillance, you're in deep trouble.)

What about laws? In the United States, there's a legal vogue for something called "Do Not Track": users can instruct their browsers to transmit a tag that says, "Don't collect information on my user." But there's no built-in compliance mechanism—we can't be sure it works unless auditors descend on IT giants' data centers to ensure they aren't cheating. In the EU, they like the idea that you own your data, which means that you have a property interest in the facts of your life and the right to demand that this "property" not be misused. But this approach is flawed, too. If there's one thing the last 15 years of Internet policy fights have taught us, it's that nothing is ever solved by ascribing propertylike rights to easily copied information.

There's still room for improvement—and profit—in code. A great deal of Internet-data harvesting is the result of permissive defaults on how our browsers handle cookies, those bits of code used to track us. Right now, there are two ways to browse the Web: turn cookies off altogether and live with the fact that many sites won't work; or turn on all cookies and accept the wholesale extraction of your Internet use habits.

Browser vendors could take a stab at the problem. For a precedent, recall what happened to pop-up ads. When the Web was young, pop-ups were everywhere. They'd appear in tiny windows that re-spawned when you closed them. They ran away from your cursor and auto-played music. Because pop-ups were the only way to command a decent rate from advertisers, the conventional wisdom was that no browser vendor could afford to block pop-ups by default, even though users hated them.

The deadlock was broken by Mozilla, a nonprofit foundation that cared mostly about serving users, not site owners or advertisers. When Mozilla's Firefox turned on pop-up blocking by default, it began to be wildly successful. The other browser vendors had no choice but to follow suit. Today, pop-ups are all but gone.

Cookie managers should come next. Imagine if your browser loaded only cookies that it thought were useful to you, rather than dozens from ad networks you never intended to interact with. Advertisers and media buyers will say the idea can't work. But the truth is that dialing down Internet tracking won't be the end of advertising. Ultimately, it could be a welcome change for those in the analytics and advertising business. Once the privacy bargain takes place without coercion, good companies will be able to build services that get more data from their users than bad companies. Right now, it seems as if everyone gets to slurp data out of your computer, regardless of whether the service is superior.

For mobile devices, we'd need more sophisticated tools. Today, mobile-app marketplaces present you with take-it-or-leave-it offers. If you want to download that Connect the Dots app to entertain your kids on a long car ride, you must give the app access to your phone number and location. What if mobile OSes were designed to let their users instruct them to lie to apps? "Whenever the Connect the Dots app wants to know where I am, make something up. When it wants my phone number, give it a random one." An experimental module for Cyanogenmod (a free/open version of the Android OS) already does this.

Far from destroying business, letting users control disclosure would create value. Design an app that I willingly give my location to (as I do with the Hailo app for ordering black cabs in London) and you'd be one of the few and proud firms with my permission to access and sell that information. Right now, the users and the analytics people are in a shooting war, but only the analytics people are armed. There's a business opportunity for a company that wants to supply arms to the rebels instead of the empire.

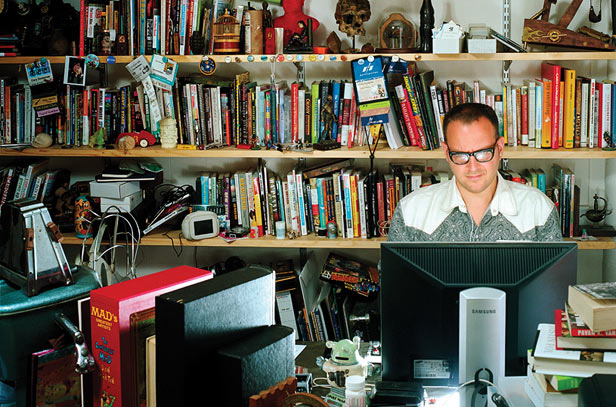

Cory Doctorow is a science fiction author, activist, journalist, and co-editor of Boing Boing