Let's assume for a minute that 3D printing becomes as good as its proponents say it will, and soon. We're talking high strength plastics, high resolution models, all at prices that the average consumer can afford.

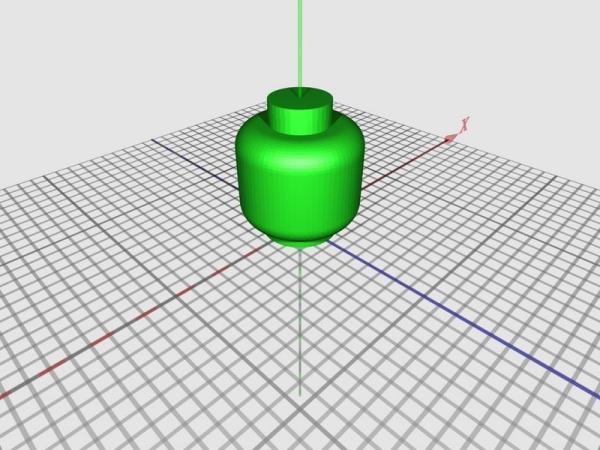

LeoCAD, A library of over 4,000 LEGO bricks, already exists. It's distributed under a creative commons attribution license, so you can pretty much do what you want with it, as long as you give credit. Makers are already constructing custom LEGO pieces on their 3D printers. The existing model for creating LEGOs, in Denmark, is surprisingly labor-intensive.

Meanwhile, "out of print" LEGO sets are eye-openingly expensive. (Pretty much every Star Wars set from the movies that weren't awful is going for at least $300.)

It seems obvious that at the point where all these trend lines meet, there's a powerful incentive for tinkerers and teenagers to start downloading plans from the internet and simply making their own sets.

In this scenario, if physical objects made from single materials follow the same trajectory as other media that were physical until they became just bits, there will at first be resistance from toymakers, in the form of lawsuits. Collectors will be sued as a deterrent to other rogues, and websites for sharing designs shut down.

Meanwhile, an underground of Makers will continue to experiment. Amateurs will collaborate to create LEGO sets and other toys that no cadre of designers in Denmark could match. Some will go pro. Gradually, the industry will adapt.

I realize that some proponents of 3D printing envision this process eating pretty much all the manufacturing on the planet. There are good reasons that won't happen. But for certain industries that are uniquely susceptible to being disrupted by better versions of today's 3D printing technology, who knows? Perhaps the YouTube of the future deals in atoms, not bits.