Friday, May 10. 2013

Brooklyn Developer Offers Up His Personal Data on Kickstarter

-----

A man had data mined himself so he can fund an app that helps others sell their own personal data.

Software developer Federico Zannier has data-mined himself, and now he’s raising money on Kickstarter to build an iPhone app and Chrome browser extension so that others can easily do the same.

Fork over $2 to the campaign and you get a day’s worth of the 1.5 gigabytes of text and 30,000 photos he’s collected from his online activities since February. That means a fun-filled 24-hours of websites, screenshots, webcam images, cursor movements, app logs, and GPS locations he’s tracked.

Is it a bargain? No, not at all—and that’s his point.

Today, companies on the web track him and everyone else and make billions selling the data. By violating his own privacy, as he puts it, he hopes that he can collect some of this value.

“If more people do the same, I’m thinking marketers could just pay us directly for our data. It might sound crazy, but so is giving all our data away for free,” he writes.

Zannier is not the first to dream up such an idea (see “A Dollar for Your Data”). One problem is that the data isn’t worth much on its own to marketers. They want to buy in bulk. That’s why Facebook and Google can make so much money. They can group people together that marketers want to reach.

So though its hard to imagine what his data is good for on its own, already with 68 backers he’s exceeded his modest funding goal of $500 for his project. If he’s successful in getting lots of people to use his data mining app, though, maybe he’ll become the next of the big data brokers.

MIT Technology Review is now exploring the issues Zannier raises in this month’s Business Report series “Big Data Gets Personal.” These articles discuss one important point that gets lost when people like Zannier dicuss their dissatisifaction with giving away their data for free: Though people are giving up more of their data than ever before, they are also getting more and more value back (see “The Data Made Me Do It.”).

Personal comment:

More and more societal questions around data... In this case, a new "business model": opening up one's own personal data (you are the product!), possibly crowd fund a mining system that would gather them from other people who act in the same way and do at best a fraction of the mining job Facebook or others could do, then get financially rewarded for breaking up one's own privacy... Instead of big corps. who do the same.

Wednesday, May 08. 2013

Stephen Wolfram on Personal Analytics

-----

The creator of the Wolfram Alpha search engine explains why he thinks your life should be measured, analyzed, and improved.

Personal control: Stephen Wolfram created the search engine Wolfram Alpha

Don’t be surprised if Stephen Wolfram, the renowned complexity theorist, software company CEO, and night owl, wants to schedule a work call with you at 9 p.m. In fact, after a decade of logging every phone call he makes, Wolfram knows the exact probability he’ll be on the phone with someone at that time: 39 percent.

Wolfram, a British-born physicist who earned a doctorate at age 20, is obsessed with data and the rules that explain data. He is the creator of the software Mathematica and of Wolfram Alpha, the nerdy “computational knowledge engine” that can tell you the distance to the moon right now, in units including light-seconds.

Now Wolfram wants to apply the same techniques to people’s personal data, an idea he calls “personal analytics.” He started with himself. In a blog post last year, Wolfram disclosed and analyzed a detailed record of his life stretching back three decades, including documents, hundreds of thousands of e-mails, and 10 years of computer keystrokes, a tally of which is e-mailed to him each morning so he can track his productivity the day before.

Last year, his company released its first consumer product in this vein, called “Personal Analytics for Facebook.” In under a minute, the software generates a detailed study of a person’s relationships and behavior on the site. My own report was revealing enough. It told me which friend lives at the highest latitude (Wicklow, Ireland) and the lowest (Brisbane, Australia), the percentage who are married (76.7 percent), and everyone’s local time. More of my friends are Scorpios than any other sign of the zodiac.

It looks just like a dashboard for your life, which Wolfram says is exactly the point. In a phone call that was recorded and whose start and stop time was entered into Wolfram’s life log, he discussed why personal analytics will make people more efficient at work and in their personal lives.

What do you typically record about yourself?

E-mails, documents, and normally, if I was in front of my computer, it would be recording keystrokes. I have a motion sensor for the room that records when I pace up and down. Also a pedometer, and I am trying to get an eye-tracking system set up, but I haven’t done that yet. Oh, and I’ve been wearing a sensor to measure my posture.

Do you think that you’re the most quantified person on the planet?

I couldn’t imagine that that was the case until maybe a year ago, when I collected together a bunch of this data and wrote a blog post on it. I was expecting that there would be people who would come forward and say, “Gosh, I’ve got way more than you.” But nobody’s come forward. I think by default that may mean I’m it, so to speak.

You coined this term “personal analytics.” What does it mean?

There’s organizational analytics, which is looking at an organization and trying to understand what the data says about its operation. Personal analytics is what you can figure out applying analytics to the person, to understand the operation of the person.

Why have you been analyzing Facebook data?

We are trying to feel out the market for personal analytics. Most people are not recording all their keystrokes like I am. But the one thing they are doing is leaving lots of digital trails, including on Facebook, and that is one of the pieces we’ve been experimenting with.

We’ve accumulated a lot of Facebook data—you’re seeing the story of people’s lives, played out in the level of data. You can see relationship status as a function of age, or the evolution of the clustering of friends at different ages. It’s really quite fascinating to see how all this stuff is just right there in the data.

Social grid: People’s friend networks on Facebook are presented as cluster diagrams.

Isn’t a lot of what you find kind of obvious? Like friends from college aren’t connected to the ones from grammar school?

Yes, but then you get a case where the data analysis is buggy. You get some curve, and your reaction is, “Oh, yeah, I understand why the curve is that way, I’ve got an argument for it.” But then, oops, there was a bug in the analysis and actually the curve is something different. That reminds you things aren’t quite so obvious. If you actually measure it, that’s doing science.

What’s the connection to the search engine you built?

Right now Wolfram Alpha is strong on public knowledge: accumulating and searching the knowledge of the civilization. But what you have to do in personal analytics is try to accumulate the knowledge of a person’s life. Then the two can actually be integrated, and I’ll give a kind of silly example. You might ask: “Who do I know that can go out into their backyard and go and look at the night sky right now?” For that you have to be able to compute who is in nighttime, who doesn’t have cloudy weather, and things like this. And we can compute all that stuff.

What do you see as the big applications in personal analytics?

Augmented memory is going to be very important. I’ve been spoiled because for years I’ve had the ability to search my e-mail and all my other records. I’ve been the CEO of the same company for 25 years, and so I never changed jobs and lost my data. That’s something that I think people will just come to expect. Pure memory augmentation is probably the first step.

The next is preëmptive information delivery. That means knowing enough about people’s history to know what they’re going to care about. Imagine someone is reading a newspaper article, and we know there is a person mentioned in it that they went to high school with, and so we can flag it. I think that’s the sort of thing it’s possible to dramatically automate and make more efficient.

Then there will be a certain segment of the population that will be into the self-improvement side of things, using analytics to learn about ourselves. Because we may have a vague sense about something, but when the pattern is explicit, we can decide, “Do we like that behavior, do we not?” Very early on, back in the 1990s, when I first analyzed my e-mail archive, I learned that a lot of e-mail threads at my company would, by a certain time of day, just resolve themselves. That was a useful thing to know, because if I jumped in too early I was just wasting my time.

What technologies are needed to do personal analytics at a large scale?

It’s data science and the whole cluster of technologies that come with that. Then it’s having computational knowledge about the world and being able to make queries in natural language. Then you need to sense things about the world, whether it’s with sensors or being able to do visual recognition to know what one is seeing. Then the final thing is just all the plumbing infrastructure to get all of these devices to communicate and feed their information to a place where one can do analysis.

Where do you stand on commercializing these ideas?

The personal analytics of Facebook for Wolfram Alpha is a deployed project, and there will be more of those in the personal-analytics space. We think we can do terrific things, but you have to be able to get to the data. That has been the holdup. The data isn’t readily available. Recently we’ve been working with different companies to try and make sure we can connect their sensors to kind of a generic analytics platform, to take people’s data, move it to the cloud, and do analytics on it.

How much better do you think that people or organizations can become with some data feedback?

I think it will be fairly dramatic. It’s like asking how much more money can you make if you track your portfolio rather than just vaguely remembering what investments you made.

Related Links:

Driving Miss dAIsy: What Google’s self-driving cars see on the road

Via Slash Gear via Computed·Blg

-----

We’ve been hearing a lot about Google‘s self-driving car lately, and we’re all probably wanting to know how exactly the search giant is able to construct such a thing and drive itself without hitting anything or anyone. A new photo has surfaced that demonstrates what Google’s self-driving vehicles see while they’re out on the town, and it looks rather frightening.

The image was tweeted by Idealab founder Bill Gross, along with a claim that the self-driving car collects almost 1GB of data every second (yes, every second). This data includes imagery of the cars surroundings in order to effectively and safely navigate roads. The image shows that the car sees its surroundings through an infrared-like camera sensor, and it even can pick out people walking on the sidewalk.

Of course, 1GB of data every second isn’t too surprising when you consider that the car has to get a 360-degree image of its surroundings at all times. The image we see above even distinguishes different objects by color and shape. For instance, pedestrians are in bright green, cars are shaped like boxes, and the road is in dark blue.

However, we’re not sure where this photo came from, so it could simply be a rendering of someone’s idea of what Google’s self-driving car sees. Either way, Google says that we could see self-driving cars make their way to public roads in the next five years or so, which actually isn’t that far off, and Tesla Motors CEO Elon Musk is even interested in developing self-driving cars as well. However, they certainly don’t come without their problems, and we’re guessing that the first batch of self-driving cars probably won’t be in 100% tip-top shape.

Electronic Sensors Printed Directly on the Skin

-----

New electronic tattoos could help monitor health during normal daily activities.

By Mike Orcutt on March 11, 2013

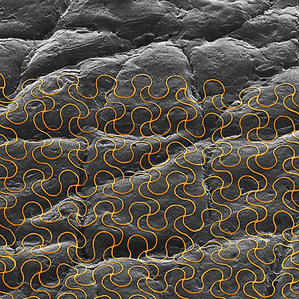

Electronic tattoo: The image shows a colorized micrograph of an ultrathin mesh electronic system mounted on a skin replica.

Taking advantage of recent advances in flexible electronics, researchers have devised a way to “print” devices directly onto the skin so people can wear them for an extended period while performing normal daily activities. Such systems could be used to track health and monitor healing near the skin’s surface, as in the case of surgical wounds.

So-called “epidermal electronics” were demonstrated previously in research from the lab of John Rogers, a materials scientist at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; the devices consist of ultrathin electrodes, electronics, sensors, and wireless power and communication systems. In theory, they could attach to the skin and record and transmit electrophysiological measurements for medical purposes. These early versions of the technology, which were designed to be applied to a thin, soft elastomer backing, were “fine for an office environment,” says Rogers, “but if you wanted to go swimming or take a shower they weren’t able to hold up.” Now, Rogers and his coworkers have figured out how to print the electronics right on the skin, making the device more durable and rugged.

“What we’ve found is that you don’t even need the elastomer backing,” Rogers says. “You can use a rubber stamp to just deliver the ultrathin mesh electronics directly to the surface of the skin.” The researchers also found that they could use commercially available “spray-on bandage” products to add a thin protective layer and bond the system to the skin in a “very robust way,” he says.

Eliminating the elastomer backing makes the device one-thirtieth as thick, and thus “more conformal to the kind of roughness that’s present naturally on the surface of the skin,” says Rogers. It can be worn for up to two weeks before the skin’s natural exfoliation process causes it to flake off.

During the two weeks that it’s attached, the device can measure things like temperature, strain, and the hydration state of the skin, all of which are useful in tracking general health and wellness. One specific application could be to monitor wound healing: if a doctor or nurse attached the system near a surgical wound before the patient left the hospital, it could take measurements and transmit the information wirelessly to the health-care providers.

Rogers says his lab is now focused on developing and refining wireless power sources and communication systems that could be integrated into the system. He says the technology could potentially be commercialized by MC10 (see “Making Stretchable Electronics”), a company he cofounded in 2008. If things go as planned, says Rogers, in about a year and half the company will be developing more sophisticated systems “that really do begin to look like the ones that we’re publishing on now.”

Friday, May 03. 2013

Moore’s Law and the Origin of Life

-----

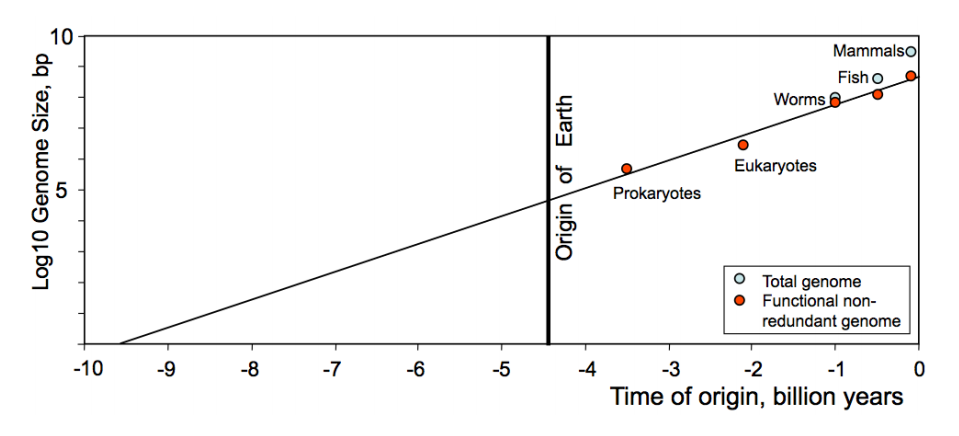

As life has evolved, its complexity has increased exponentially, just like Moore’s law. Now geneticists have extrapolated this trend backwards and found that by this measure, life is older than the Earth itself.

Here’s an interesting idea. Moore’s Law states that the number of transistors on an integrated circuit doubles every two years or so. That has produced an exponential increase in the number of transistors on microchips and continues to do so.

But if an observer today was to measure this rate of increase, it would be straightforward to extrapolate backwards and work out when the number of transistors on a chip was zero. In other words, the date when microchips were first developed in the 1960s.

A similar process works with scientific publications. Between 1990 and 1960, they doubled in number every 15 years or so. Extrapolating this backwards gives the origin of scientific publication as 1710, about the time of Isaac Newton.

Today, Alexei Sharov at the National Institute on Ageing in Baltimore and his mate Richard Gordon at the Gulf Specimen Marine Laboratory in Florida, have taken a similar to complexity and life.

These guys argue that it’s possible to measure the complexity of life and the rate at which it has increased from prokaryotes to eukaryotes to more complex creatures such as worms, fish and finally mammals. That produces a clear exponential increase identical to that behind Moore’s Law although in this case the doubling time is 376 million years rather than two years.

That raises an interesting question. What happens if you extrapolate backwards to the point of no complexity–the origin of life?

Sharov and Gordon say that the evidence by this measure is clear. “Linear regression of genetic complexity (on a log scale) extrapolated back to just one base pair suggests the time of the origin of life = 9.7 ± 2.5 billion years ago,” they say.

And since the Earth is only 4.5 billion years old, that raises a whole series of other questions. Not least of these is how and where did life begin.

Of course, there are many points to debate in this analysis. The nature of evolution is filled with subtleties that most biologists would agree we do not yet fully understand.

For example, is it reasonable to think that the complexity of life has increased at the same rate throughout Earth’s history? Perhaps the early steps in the origin of life created complexity much more quickly than evolution does now, which will allow the timescale to be squeezed into the lifespan of the Earth.

Sharov and Gorden reject this argument saying that it is suspiciously similar to arguments that squeeze the origin of life into the timespan outlined in the biblical Book of Genesis.

Let’s suppose for a minute that these guys are correct and ask about the implications of the idea. They say there is good evidence that bacterial spores can be rejuvenated after many millions of years, perhaps stored in ice.

They also point out that astronomers believe that the Sun formed from the remnants of an earlier star, so it would be no surprise that life from this period might be preserved in the gas, dust and ice clouds that remained. By this way of thinking, life on Earth is a continuation of a process that began many billions of years earlier around our star’s forerunner.

Sharov and Gordon say their interpretation also explains the Fermi paradox, which raises the question that if the universe is filled with intelligent life, why can’t we see evidence of it.

However, if life takes 10 billion years to evolve to the level of complexity associated with humans, then we may be among the first, if not the first, intelligent civilisation in our galaxy. And this is the reason why when we gaze into space, we do not yet see signs of other intelligent species.

There’s no question that this is a controversial idea that will ruffle more than a few feathers amongst evolutionary theorists.

But it is also provocative, interesting and exciting. All the more reason to debate it in detail.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1304.3381: Life Before Earth

fabric | rblg

This blog is the survey website of fabric | ch - studio for architecture, interaction and research.

We curate and reblog articles, researches, writings, exhibitions and projects that we notice and find interesting during our everyday practice and readings.

Most articles concern the intertwined fields of architecture, territory, art, interaction design, thinking and science. From time to time, we also publish documentation about our own work and research, immersed among these related resources and inspirations.

This website is used by fabric | ch as archive, references and resources. It is shared with all those interested in the same topics as we are, in the hope that they will also find valuable references and content in it.