Thursday, February 23. 2012

-----

While the subject of online piracy is certainly nothing new, the recent protests against SOPA and the federal raid on Megaupload have thrust the issue into mainstream media. More than ever, people are discussing the controversial topic while content creators scramble to find a way to try to either shut down or punish sites and individuals that take part in the practice. Despite these efforts, online piracy continues to be a thorn in Big Media’s side. With the digital media arena all but conquered by piracy, the infamous site The Pirate Bay (TPB) has begun looking to the next frontier to be explored and exploited. According to a post on its blog, TPB has declared that physical objects named “physibles” are the next area to be traded and shared across global digital smuggling routes.

TPB defines a physible as “data objects that are able (and feasible) to become physical.” Namely, items that can be created using 3D scanning and printing technologies, both of which have become much cheaper for you to actually own in your home. At CES this year, MakerBot Industries introduced its latest model which is capable of printing objects in two colors and costs under $2,000. With the price of such devices continuing to drop, 3D printing is going to be part of everyday life in the near future. Where piracy is going to come in is the exchange of the files (3D models) necessary to create these objects.

A 3D printer is essentially a “CAD-CAM” process. You use a computer-aided design (CAD) program to design a physical object that you want made, and then feed it into a computer-aided machining (CAM) device for creation. The biggest difference is that traditional CAM setups, the process is about milling an existing piece of metal, drilling holes and using water jets to carve the piece into the desired configuration. In 3D printing you use extrusion to actually create what is illustrated in the CAD file. Those CAD files are the physibles that TPB is talking about, since they are digital they are going to be as easily transferred as an MP3 or movie is right now.

It isn’t too far outside the realm of possibility that once 3D printing becomes a part of everyday life, companies will begin to sell the CAD files and the rights to be able to print proprietary items. If the technology continues to advance at the same rate, in 10 or 20 years you might be printing a new pair of Nikes for your child’s basketball game right in your home (kind of like the 3D printed sneakers pictured above). Instead of going to the mall and paying $120 for a physical pair of shoes in a retail outlet, you will pay Nike directly on the internet and receive the file necessary to direct your printer to create the sneakers. Of course, companies will do their level best to create DRM on these objects so that you can’t freely just print pair after pair of shoes, but like all digital media it will be broken be enterprising individuals.

TPB has already created a physibles category on its site, allowing you to download plans to be able to print out such things as the famous Pirate Bay Ship and a 1970 Chevy hot rod. For now it’s going to be filled with user-created content, but in the future you can count on it being stocked with plans for DRM-protected objects.

Tuesday, February 14. 2012

-----

de Nicolas

Back to failing technologies… this piece on CNN Money from 2004 gives an intriguing snapshot of the problems encountered by “users” of the Prada building designed by Rem Koolhaas. As described in this article, this cutting-edge architecture was supposed to “revolutionize the luxury experience” through “a wireless network to link every item to an Oracle inventory database in real time using radio frequency identification (RFID) tags on the clothes. The staff would roam the floor armed with PDAs to check whether items were in stock, and customers could do the same through touchscreens in the dressing rooms”.

Some excerpts that I found relevant to my interests in technological accidents and problems:

“But most of the flashy technology today sits idle, abandoned by employees who never quite embraced computing chic and are now too overwhelmed by large crowds to coolly assist shoppers with handhelds. On top of that, many gadgets, such as automated dressing-room doors and touchscreens, are either malfunctioning or ignored

(…)

In part because of the crowds, the clerks appear to have lost interest in the custom-made PDAs from Ide. During multiple visits this winter, only once was a PDA spied in public–lying unused on a shelf–and on weekends, one employee noted, “we put them away, so the tourists don’t play with them.”

When another clerk was asked why he was heading to the back of the store to search for a pair of pants instead of consulting the handheld, he replied, “We don’t really use them anymore,” explaining that a lag between the sales and inventory systems caused the PDAs to report items being in stock when they weren’t. “It’s just faster to go look,” he concluded. “Retailers implementing these systems have to think about how they train their employees and make sure they understand them,”

(…)

Also aging poorly are the user-unfriendly dressing rooms. Packed with experimental tech, the clear-glass chambers were designed to open and close automatically at the tap of a foot pedal, then turn opaque when a second pedal sent an electric current through the glass. Inside, an RFID-aware rack would recognize a customer’s selections and display them on a touchscreen linked to the inventory system.

In practice, the process was hardly that smooth. Many shoppers never quite understood the pedals, and fashionistas whispered about customers who disrobed in full view, thinking the door had turned opaque. That’s no longer a problem, since the staff usually leaves the glass opaque, but often the doors get stuck. In addition, some of the chambers are open only to VIP customers during peak traffic times. “They shut them down on the weekends or when there’s a lot of traffic in the store,” says Darnell Vanderpool, a manager at the SoHo store, “because otherwise kids would toy with them.”

On several recent occasions, the RFID “closet” failed to recognize the Texas Instruments-made tags, and the touchscreen was either blank or broadcasting random video loops. During another visit, the system recognized the clothes–and promptly crashed. “[The dressing rooms] are too delicate for high traffic,” says consultant Dixon. “Out of the four or five ideas for the dressing rooms, only one of them is tough enough.” That feature is the “magic mirror,” which video-captures a customer’s rear view for an onscreen close-up, whether the shopper wants one or not.“

Why do I blog this? It’s a rather good account of technological failures, possibly useful to show the pain points of Smart Architecture/Cities. The reasons explained here are all intriguing and some of them can be turned into opportunities too (“otherwise kids would toy with them.”)

That said, it’d be curious to know how the situation has changed in 7 years.

Wednesday, February 01. 2012

-----

de Casey Gollan

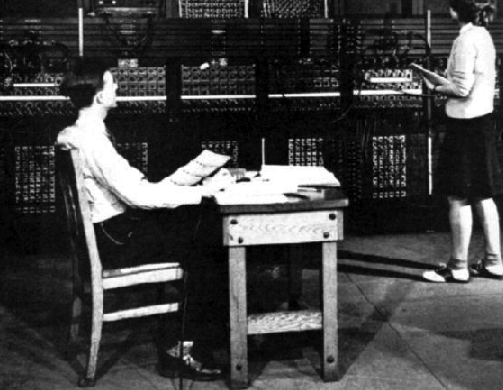

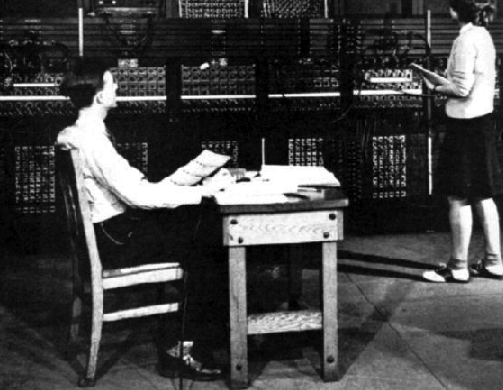

ENIAC programmers, late 1940s. (U.S. military photo, Redstone Arsenal Archives, Huntsville, Alabama), from Programmed Visions by Wendy Hui Kyong Chun.

After “getting fit” and whatever else people typically declare to be their new year’s resolutions, this year’s most popular goal is surprisingly nerdy: learning to code. Within the first week of 2012, over 250,000 people, including New York’s mayor Michael Bloomberg, had signed up for weekly interactive programming lessons on a site called Code Year. The website promises to put its users “on the path to building great websites, games, and apps.” But as New Yorker web editor Blake Eskin writes, “The Code Year campaign also taps into deeper feelings of inadequacy... If you can code, the implicit promise is that you will not be wiped out by the enormous waves of digital change sweeping through our economy and society.”

If the entrepreneurs behind Code Year (and the masses of users they’ve signed up for lessons) are all hoping to ride the wave of digital change, Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, a professor of Modern Culture and Media at Brown University, is the academic trying to pause for a moment to take stock of the present situation and see where software is actually headed. All the frenzy about apps and “the cloud,” Chun argues, is just another turn in the “cycles of obsolescence and renewal” that define new media. The real change, which Chun lays out in her book Programmed Visions: Software and Memory, is that “programmability,” the logic of computers, has come to reach beyond screens into both the systems of government and economics and the metaphors we use to make sense of the world.

“Without [computers, human and mechanical],” writes Chun, “there would be no government, no corporations, no schools, no global marketplace, or, at the very least, they would be difficult to operate...Computers, understood as networked software and hardware machines, are—or perhaps more precisely set the grounds for—neoliberal governmental technologies...not simply through the problems (population genetics, bioinformatics, nuclear weapons, state welfare, and climate) they make it possible to both pose and solve, but also through their very logos, their embodiment of logic.”

To illustrate this logic, Chun draws extensively on history, theory, and detailed technical explanations, enriching cursory understandings of software. “Understanding software as a thing,” she writes, “means engaging its odd materializations and visualizations closely and refusing to reduce software to codes and algorithms—readily readable objects—by grappling with its simultaneous ambiguity and specificity.” Indeed, Chun spends a lot of time specifying computer terms. What's the difference between hardware, software, firmware, and wetware? Source code, compiled code, and written instructions? What is a thing and how did software become one? Even for a fairly nerdy computer user there’s a lot to pick up on. The book really shines, however, when Chun waxes poetic on the more ambiguous aspects of software.

The term “vaporware” refers to software that’s announced and advertised but never actually released for use, such as Ted Nelson’s infamous Xanadu project. Vaporware is problematic when it comes to theory because grand ideas and slick renderings rarely (if ever) align with the way technology looks and works in real life. Geert Lovink, Alexander Galloway, and others have called to banish “vapor theory,” theory built on hypothetical ideas about software rather than instantiations of it, which Lovink criticizes as, “gaseous flapping of the gums...generated with little exposure, much less involvement with those self-same technologies and artworks.” Chun concedes that while this embargo on vapor has been essential to grounding new media studies, “a rigorous engagement with software makes new media studies more, rather than less, vapory.” Vapor is not incidental to software, she argues, but actually essential to its understanding. This is what makes Chun’s theories exciting to follow: she engages renderings, dreams, and misunderstandings about technology rather than casting them aside. The key source of these misunderstandings is the use of the computer as metaphor.

People in previous generations conceptualized the world around them using technologies like clocks and steam engines. While these analog, mechanical devices are intricate, if one were to take apart a clock and and put it back together its inner workings could be understood. Digital computers are more complex because they are made of both tangible chips and immaterial codes, neither of which are intuitive to deconstruct. Further, all software interfaces, like the “paintbrush” tool in Photoshop, are metaphors themselves. “Who completely understands what one’s computer is actually doing at any given moment?” asks Chun, knowing that the answer is nobody. Yet this murky recursion of “unknowability” and vapors is exactly why Chun finds software to be such an apt metaphor for the world we live in. Recalling Stewart Brand’s call for a picture of the whole earth in 1968, Chun poses the question: what would a picture of the whole Internet look like? Except, in this case, to find out may not be the point. In the way that the stock market is based on speculation—virally spreading fear about the future of a company (as opposed to concrete evidence or actual bad management decisions) can cause a stock to tank—a technologized world is increasingly based on conjecture. In its unseeable, untouchable, and effectively unknowable nature, the computer represents the lens we need in order to think about the enormous and incomprehensible forces of social, economic, and political power that govern our lives. “[Software’s] ghostly interfaces embody—conceptually, metaphorically, virtually—a way to navigate our increasingly complex world,” writes Chun.

The book looks at a broad range of examples from artists, scholars, and technologists to situate “programmability” in relation to everything from global systems like capitalist economics, neoliberal politics, and knowledge production to those of the mind and body: gender, race, and the structure of thought. The footnotes are full of interesting paths waiting to be followed: Frederick P. Brooks on why programming is fun and hacking is addictive, Ben Shneiderman on direct manipulation interfaces, Brenda Laurel on computers as theatre and how that relates to skeuomorphism, and Thomas Y. Levin on the temporality of surveillance, to name just a few. While it’s tempting to look to this web of ideas and the history of computing as an answer for why things are the way they are today, Chun's point in invoking all these voices is that it’s not that clear cut.

Some of the book’s propositions about our relationship to computers seem overblown: a priestly source of power, a form of magic, code as a fetish. If nothing else, these phrases are provocative and point to how potent Chun finds software to be in the world today. As more and more people find themselves able to create things out of code, it feels critical to understand software on both a practical and fundamental level.

|