Sunday, February 26. 2012

-----

de rholmes

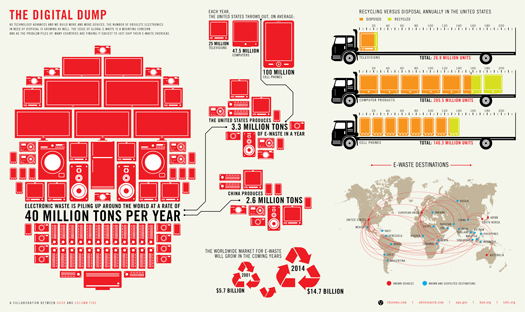

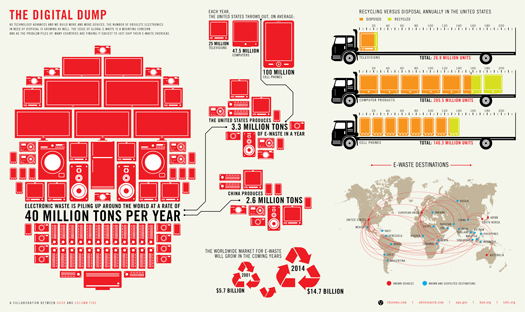

["The Digital Dump", a graphic about e-waste from Good.is's "Transparency" series and Column Five Media.]

Mostly for our own purposes (keeping track of things we see), we’ve started Visibility, a tumblr collecting items related to An Atlas of iPhone Landscapes. I make no promises about how frequently it will or won’t be updated, but if you’re particularly interested in the topic, you can follow the tumblr or grab the feed.

Tuesday, February 14. 2012

-----

de Nicolas

Back to failing technologies… this piece on CNN Money from 2004 gives an intriguing snapshot of the problems encountered by “users” of the Prada building designed by Rem Koolhaas. As described in this article, this cutting-edge architecture was supposed to “revolutionize the luxury experience” through “a wireless network to link every item to an Oracle inventory database in real time using radio frequency identification (RFID) tags on the clothes. The staff would roam the floor armed with PDAs to check whether items were in stock, and customers could do the same through touchscreens in the dressing rooms”.

Some excerpts that I found relevant to my interests in technological accidents and problems:

“But most of the flashy technology today sits idle, abandoned by employees who never quite embraced computing chic and are now too overwhelmed by large crowds to coolly assist shoppers with handhelds. On top of that, many gadgets, such as automated dressing-room doors and touchscreens, are either malfunctioning or ignored

(…)

In part because of the crowds, the clerks appear to have lost interest in the custom-made PDAs from Ide. During multiple visits this winter, only once was a PDA spied in public–lying unused on a shelf–and on weekends, one employee noted, “we put them away, so the tourists don’t play with them.”

When another clerk was asked why he was heading to the back of the store to search for a pair of pants instead of consulting the handheld, he replied, “We don’t really use them anymore,” explaining that a lag between the sales and inventory systems caused the PDAs to report items being in stock when they weren’t. “It’s just faster to go look,” he concluded. “Retailers implementing these systems have to think about how they train their employees and make sure they understand them,”

(…)

Also aging poorly are the user-unfriendly dressing rooms. Packed with experimental tech, the clear-glass chambers were designed to open and close automatically at the tap of a foot pedal, then turn opaque when a second pedal sent an electric current through the glass. Inside, an RFID-aware rack would recognize a customer’s selections and display them on a touchscreen linked to the inventory system.

In practice, the process was hardly that smooth. Many shoppers never quite understood the pedals, and fashionistas whispered about customers who disrobed in full view, thinking the door had turned opaque. That’s no longer a problem, since the staff usually leaves the glass opaque, but often the doors get stuck. In addition, some of the chambers are open only to VIP customers during peak traffic times. “They shut them down on the weekends or when there’s a lot of traffic in the store,” says Darnell Vanderpool, a manager at the SoHo store, “because otherwise kids would toy with them.”

On several recent occasions, the RFID “closet” failed to recognize the Texas Instruments-made tags, and the touchscreen was either blank or broadcasting random video loops. During another visit, the system recognized the clothes–and promptly crashed. “[The dressing rooms] are too delicate for high traffic,” says consultant Dixon. “Out of the four or five ideas for the dressing rooms, only one of them is tough enough.” That feature is the “magic mirror,” which video-captures a customer’s rear view for an onscreen close-up, whether the shopper wants one or not.“

Why do I blog this? It’s a rather good account of technological failures, possibly useful to show the pain points of Smart Architecture/Cities. The reasons explained here are all intriguing and some of them can be turned into opportunities too (“otherwise kids would toy with them.”)

That said, it’d be curious to know how the situation has changed in 7 years.

Monday, February 13. 2012

Via MIT Technology Review (blog)

-----

Before you dismiss it as a fad, consider the evolution of 2-D printing.

By Tim Maly

|

The Miehle P.P. & Mfg. Co. 1905 printing press. Credit: Public Domain / Wikipedia.

|

I'd like to sneak up on the question of 3-D printing by way of boring old 2-D printing.

Typography used to be heavy industry. The companies that make typefaces are still called foundries because there was a time when letters were made of metal. When you got enough of them together to reliably set a whole book or whatever, you had a serious amount of hardware on your hands. Fonts were forged. Picking a new one was a large capital investment. Today, fonts are a thing that you pick from a drop-down menu and printers are things in your home that can render just about any typeface you can imagine.

We went from massive metal fonts and centralized presses to the current desktop regime by degrees. In the early days of desktop printing, we had the dot-matrix. The deal was simple: "We give you one crappy font and you need specialized paper but you can do this at home". It wasn’t useful for much, but it was useful for some things, and used frequently enough that it was worth developing improvements.

Today, it's reasonable for most people to have a pile of paper and a printer that cost them next to nothing and for businesses to have stockrooms laden with the raw material of documents. Print shops have had to stay a step ahead, selling convenience, their ability to print nicer things on bigger formats, or the economics of scale.

I want you to bear this in mind, when you consider Chris Mims' argument that the idea that 3-D printing will be a mature technology "on any reasonable time scale" is absurd.

Chris is right that 3-D printing as it stands isn't a replacement for the contemporary industrial supply chain. It's clearly a transitional technology. The materials suck. The resolution is terrible. The objects are fragile. You can't recycle the stuff.

Maybe early home 3-D printers use only plastic and can only make objects that fall within certain performance restrictions. Maybe it starts out as, like, jewelry, the latest model toys, and parts for Jay Leno's car. But there's no way that lasts. People are already working on the problem. They are working especially hard on the materials problem.

At the same time, it's not hard to imagine a convergence from the other direction. Some materials and formats will fall out of favor because they are hard to make rapidly. Think of how most documents are 8.5×11 (or A4) these days. It's just not worth the hassle of wrangling dozens of paper formats.

It's also important not to confuse 3-D printing & desktop-class fabrication. These aren't the same thing. There is more to desktop manufacturing than 3-D printers. A well-appointed contemporary maker workshop has working CNC mills, lathes, and laser cutters. A well-appointed design studio has the tools to make and finish prototypes that look very nice indeed. Aside from the 3-D printer, none of these tools are terribly science-fictional; they're well-established technologies that happen to be getting cheaper from year to year.

Something interesting happens when the cost of tooling-up falls. There comes a point where your production runs are small enough that the economies of scale that justify container ships from China stop working. There comes a point where making new things isn't a capital investment but simply a marginal one. Fab shops are already popping up, just like print shops did.

Copyright Technology Review 2012.

Wednesday, February 01. 2012

-----

de Casey Gollan

ENIAC programmers, late 1940s. (U.S. military photo, Redstone Arsenal Archives, Huntsville, Alabama), from Programmed Visions by Wendy Hui Kyong Chun.

After “getting fit” and whatever else people typically declare to be their new year’s resolutions, this year’s most popular goal is surprisingly nerdy: learning to code. Within the first week of 2012, over 250,000 people, including New York’s mayor Michael Bloomberg, had signed up for weekly interactive programming lessons on a site called Code Year. The website promises to put its users “on the path to building great websites, games, and apps.” But as New Yorker web editor Blake Eskin writes, “The Code Year campaign also taps into deeper feelings of inadequacy... If you can code, the implicit promise is that you will not be wiped out by the enormous waves of digital change sweeping through our economy and society.”

If the entrepreneurs behind Code Year (and the masses of users they’ve signed up for lessons) are all hoping to ride the wave of digital change, Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, a professor of Modern Culture and Media at Brown University, is the academic trying to pause for a moment to take stock of the present situation and see where software is actually headed. All the frenzy about apps and “the cloud,” Chun argues, is just another turn in the “cycles of obsolescence and renewal” that define new media. The real change, which Chun lays out in her book Programmed Visions: Software and Memory, is that “programmability,” the logic of computers, has come to reach beyond screens into both the systems of government and economics and the metaphors we use to make sense of the world.

“Without [computers, human and mechanical],” writes Chun, “there would be no government, no corporations, no schools, no global marketplace, or, at the very least, they would be difficult to operate...Computers, understood as networked software and hardware machines, are—or perhaps more precisely set the grounds for—neoliberal governmental technologies...not simply through the problems (population genetics, bioinformatics, nuclear weapons, state welfare, and climate) they make it possible to both pose and solve, but also through their very logos, their embodiment of logic.”

To illustrate this logic, Chun draws extensively on history, theory, and detailed technical explanations, enriching cursory understandings of software. “Understanding software as a thing,” she writes, “means engaging its odd materializations and visualizations closely and refusing to reduce software to codes and algorithms—readily readable objects—by grappling with its simultaneous ambiguity and specificity.” Indeed, Chun spends a lot of time specifying computer terms. What's the difference between hardware, software, firmware, and wetware? Source code, compiled code, and written instructions? What is a thing and how did software become one? Even for a fairly nerdy computer user there’s a lot to pick up on. The book really shines, however, when Chun waxes poetic on the more ambiguous aspects of software.

The term “vaporware” refers to software that’s announced and advertised but never actually released for use, such as Ted Nelson’s infamous Xanadu project. Vaporware is problematic when it comes to theory because grand ideas and slick renderings rarely (if ever) align with the way technology looks and works in real life. Geert Lovink, Alexander Galloway, and others have called to banish “vapor theory,” theory built on hypothetical ideas about software rather than instantiations of it, which Lovink criticizes as, “gaseous flapping of the gums...generated with little exposure, much less involvement with those self-same technologies and artworks.” Chun concedes that while this embargo on vapor has been essential to grounding new media studies, “a rigorous engagement with software makes new media studies more, rather than less, vapory.” Vapor is not incidental to software, she argues, but actually essential to its understanding. This is what makes Chun’s theories exciting to follow: she engages renderings, dreams, and misunderstandings about technology rather than casting them aside. The key source of these misunderstandings is the use of the computer as metaphor.

People in previous generations conceptualized the world around them using technologies like clocks and steam engines. While these analog, mechanical devices are intricate, if one were to take apart a clock and and put it back together its inner workings could be understood. Digital computers are more complex because they are made of both tangible chips and immaterial codes, neither of which are intuitive to deconstruct. Further, all software interfaces, like the “paintbrush” tool in Photoshop, are metaphors themselves. “Who completely understands what one’s computer is actually doing at any given moment?” asks Chun, knowing that the answer is nobody. Yet this murky recursion of “unknowability” and vapors is exactly why Chun finds software to be such an apt metaphor for the world we live in. Recalling Stewart Brand’s call for a picture of the whole earth in 1968, Chun poses the question: what would a picture of the whole Internet look like? Except, in this case, to find out may not be the point. In the way that the stock market is based on speculation—virally spreading fear about the future of a company (as opposed to concrete evidence or actual bad management decisions) can cause a stock to tank—a technologized world is increasingly based on conjecture. In its unseeable, untouchable, and effectively unknowable nature, the computer represents the lens we need in order to think about the enormous and incomprehensible forces of social, economic, and political power that govern our lives. “[Software’s] ghostly interfaces embody—conceptually, metaphorically, virtually—a way to navigate our increasingly complex world,” writes Chun.

The book looks at a broad range of examples from artists, scholars, and technologists to situate “programmability” in relation to everything from global systems like capitalist economics, neoliberal politics, and knowledge production to those of the mind and body: gender, race, and the structure of thought. The footnotes are full of interesting paths waiting to be followed: Frederick P. Brooks on why programming is fun and hacking is addictive, Ben Shneiderman on direct manipulation interfaces, Brenda Laurel on computers as theatre and how that relates to skeuomorphism, and Thomas Y. Levin on the temporality of surveillance, to name just a few. While it’s tempting to look to this web of ideas and the history of computing as an answer for why things are the way they are today, Chun's point in invoking all these voices is that it’s not that clear cut.

Some of the book’s propositions about our relationship to computers seem overblown: a priestly source of power, a form of magic, code as a fetish. If nothing else, these phrases are provocative and point to how potent Chun finds software to be in the world today. As more and more people find themselves able to create things out of code, it feels critical to understand software on both a practical and fundamental level.

|