Wednesday, October 27. 2010

Where do Websites go to Die?

Via dpr-barcelona

In 1998 google was created.

12 years ago there were no blogs.

6 years ago YouTube did not exist, neither Facebook.

Twitter was created 4 years ago and the iPhone was born at the same time.*

In the year 3ϕϕ there will be the Dead Website Archive at the Munižaba cave [Croatia].

Following the same mission of the International Internet Preservation Consortium [IIPC], that is to acquire, preserve and make accessible knowledge and information from the Internet for future generations everywhere, and based in the same kind of philosophy as the project The Ruins of Twitter on the idea that the current times are the age of the data-loss paranoia… what if to have an archive of dead websites?

From David Garcia Studio‘s MAP 003: Archive, we can read:

Hundreds of websites are shut down daily, constantly eliminating traces of our present culture. Although services exist which make random “back ups” of the Internet, they are as robust as the media they are saved on to, and digital media has a frighteningly short lifespan.

According to Iliesiu, our behavior is based on an obsessive back-up system, where we save, we update and upgrade, in a race with crashing computers and obsolete hardware. With this obsesive behaviour and related with an article by E. Alan that we found a few years ago, it is understandable to have the same kind of concerns that Alan had when he wondered what happens to these “dead websites” after their death? And then he added: “Is there an archive where you can trace them? Does anyone keep statistics how many websites are dying daily or monthly? Which country or which category has actually the biggest cementry of websites?” Well, now it seems that we will be able to answer to this questions and say that dead websites will go to the Dead Website Archive in Munižaba.

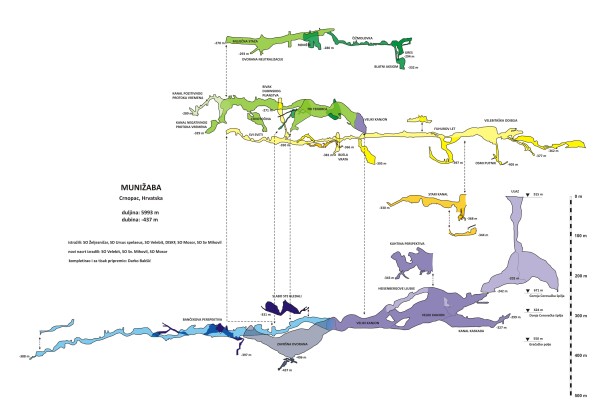

Munižaba cave. Source: Speleologija

Munižaba cave, section. Source: Speleologija

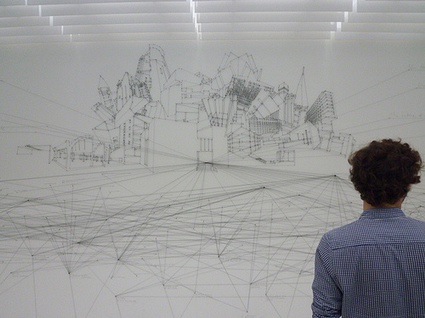

The Dead Website Archive proposed by David Garcia Studio, will convert what was once virtual and plural while in use, to a physical and single reality when it has been removed from the Web. The archive will be located over Europe’s largest cave in Croatia and it’s task is to select the relevant shut-down-websites, and proceed to laser cut the contents of the full site into thin polycarbonate A4 sheets.

This is a response to the call for attention to the urgent need to collect and preserve the world’s cultural and historical record, that is increasingly being produced digitally and in no other form, as the Library of Congress recently published:

It took two centuries for the Library of Congress to acquire its 29 million books and 105 million other items: manuscripts, motion pictures, sound recordings, maps, prints, photographs. Today it takes only 15 minutes for the world to produce an equal amount of information in digital form.

According to Jim Barksdale and Francine Berman, an estimated 44 percent of Web sites that existed in 1998 vanished without a trace within just one year. The average life span of a Web site is only 44 to 75 days. In this context, with websites dying what we can call “a strange death”, we can’t stop asking where did they go?… and start understanding the need to have a dead website archive.

Dead Website Archive at the Munižaba cave by David Garcia Studio

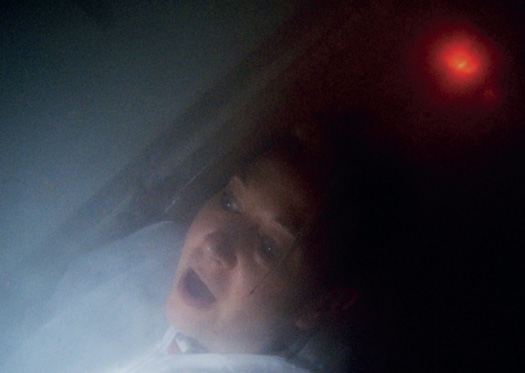

Dead Website Archive at the Munižaba cave by David Garcia Studio

If we agree with the Library of Congress on their definition for “Web Archiving” as the process of collecting documents from the Internet and bringing them under local control for the purpose of preserving the documents in an archive, we should also agree that the archiving process occupies a large amount of space. That’s why choosing the right place for this archive is also an important issue.

According to the Data Centre Knowledge, the ideal location for a Data Centre is one that can accommodate growth and change and is also protected from hazards with an easy access. This kind of locations can be as diverse as urban apartments or underground bunkers and silos; so, the idea to “colonize” the Munižaba cave and build there a bridge that acts as a building, where researchers can stay, work and descend to the cave when acces to the archive is required is quite creative. As David Garcia Studio explains:

In the depth of this natural hollow, the “website sheets” are arranged chronologically, placed directly upon the topography, lit by LEDs and visited as one would a library, or a forest. Down here, websites become unique realities, housed in a single location, guaranteeing a lifespan of hundreds of years; an alternative to the fleeting existence of a hard disk.

The cave allows the user to select and photocopy an archived “web site” from the cave floor, or project it on large screens for group sudy.

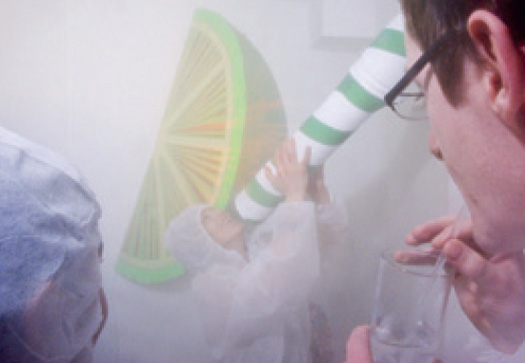

Bridge as a building at the Dead Website Archive by David Garcia Studio

Web sites projected on large screens for group sudy at the Dead Website Archive

The Munižaba Cave is located in Crnopac [Croatia]. With an horizontal length of 6947 m and a depth of -437 m it is the perfect place to house the dead website archive, as David Garcia Studio is proposing. The counterpoint between arduous work that is required to move about in such an impressive natural space, and the conrast to the easy access and plural digital reality that defined the website when it was “alive”, is a way to remind us about the ephemeral life of some of our actions when we create and share contents.

Bridge as a building at the Dead Website Archive by David Garcia Studio

Some people think that archives have reached such epidemic proportions that, the digital revolution has not been able to solve the problem, but in fact it has aggravated it. Can we say that the Dead Website Archive will help us to solve this problem?

We’re not sure about the answer… whe can only speculate on the emotion of a future researcher while his eyes are discovering “ancient messages” in foreign languages, hidden in the caves and blurring into subterranean fountainheads:

“Estoy aquí entre archivos y kilos de bits… aquí debajo, ¿no me ves? Aquí…” -@pacogonzalez*

—–

The Dead Website Archive was published on MAP 003 Archive, a project by David Garcia Studio.

* Thanks to @pacogonzalez for the initial facts and the hidden message “I’m here, between archives and tons of bits… down here, don’t you see me? Here…”

Related reading:

- The Ruins of Twitter by Ioana Iliesiu

- Bloggers in the Archive by Geoff Manaugh

- Meeting the Challenge: Saving the World Wide Web at the Library of Congress

Related Links:

Monday, October 25. 2010

Video: “A Necessary Ruin: The Story of Buckminster Fuller and the Union Tank Car Dome”

Via Archdaily

-----

A Necessary Ruin: The Story of Buckminster Fuller and the Union Tank Car Dome from Evan Mather on Vimeo.

Upon its completion in October 1958, the Union Tank Car Dome, located north of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, was the largest clear-span structure in the world. Based on the engineering principles of the visionary design scientist and philosopher Buckminster Fuller, this geodesic dome was, at 384 feet in diameter, the first large scale example of this building type.

“A Necessary Ruin” tells the history of the Union Tank Car Dome via interviews with architects, engineers, preservationists, media, and artists; animated sequences demonstrating the operation of the facility; and hundreds of rare photographs and video segments taken during the dome’s construction, decline, and demolition.

Visit handcraftedfilms.com for more information and to purchase the DVD.

Related Links:

Friday, October 22. 2010

Dangers in the Air: Aerosol Architecture and Invisible Landscapes

-----

In late 2009, researchers at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, validated some horrifying claims: 24 slaughterhouse workers from two states had reported symptoms ranging from numbness to paralysis. What all the claims had in common was the workers' location at or near the “head table” in pork processing plants where pig heads are butchered. Investigations revealed that the workers had inhaled a mist of pig brains, and that this had in turn triggered an auto-immune response, causing neurological disorders. This was not only disgusting; it was also a surprise to scientists to learn that “aerosolized” pig brains, the microscopic industrial byproduct of mechanically blowing out every last piece of flesh from a pig's head, can impair the motor functions of anyone who breathes them in.

Perhaps it shouldn't have been a surprise. Almost a century ago, the air we breathe was first understood to be, potentially, a weapon — an innovation that was, like so many innovations, born in warfare, and which marked a turning point for the modern mind. So argues German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk in Terror from the Air, his exploration of the rise of environmental warfare, starting with the German army's deployment of chlorine gas against French and Canadian soldiers at the battle of Ypres in 1915. [1] With the invention of poison gas, the air itself — the imperceptible atmosphere that surrounds us — could be activated, differentiated and unleashed as a killer — as a kind of anti-air. It could be weaponized, and as such used against civilian as well as military populations, a latent concern that became newly pressing in the post-Sept. 11 autumn of 2001 when somebody, most likely a scientist in an American army lab, sent packets of anthrax spores though the U.S. mail, killing five people and infecting seventeen others who breathed in the dust that became airborne when they opened the envelopes.

As architecture theorist Enrique Ramírez has noted, on his site, aggregat456.com, all airborne attacks — he traces a line from the U.S Army's Chemical Warfare Service in Japan during World War II to the 1995 sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway, attributed to the Aum Shinrikyo cult — take malign advantage of the diffusing properties of the air, and of the workings of our pulmonary systems, which deliver the oxygen our bodies need to live. Indeed, the history of weaponized air is long and sometimes macabre. For the past couple of decades — to cite just one more example — the U.S. military has been contaminating otherwise safely breathable air by shooting uranium-tipped bullets. When fired, the bullets become extremely hot, which enables them to pierce armored tanks. Such bullets have been used on battlefields from Kosovo to Baghdad, and also on bases such as the former practice range at Vieques, Puerto Rico. They leave a barely detectable plume in their wake, polluting the air and exposing local civilians to the dangers of radioactivity.

Air in Art and Architecture

Aerosolized pig brains and various forms of weaponized air suggest we have underestimated the presence of air, and what it can potentially do. Whatever the spur, we need to take seriously the materiality of air. And today, in fact, a growing number of artists and architects are engaging air in new ways. They are exploring air as a design component, studying how airborne particles can be manipulated into various textures, surfaces and spaces. They are transforming the scales at which architects typically work. And they are bringing the multiple temporalities of air into play through designs that actually collect and archive air from different times. This work could bring about a new consciousness and perhaps an expanded understanding of the meaning of a public architecture — an effort to reclaim the air from those who've attempted to control it in irresponsible and dangerous ways.

Some of the designers who have begun this reclamation project use whimsical strategies, experimenting with tints, adhesives, odors, vapors and other airborne media to harness the latent architectural possibilities of our atmosphere. Especially notable is the work of the Madrid architect Nerea Calvillo, who refers to urban air as “invisible layers that also are landscapes,” and who has worked with a multidisciplinary team to investigate and reveal the hidden or less apparent geographies of cities. Calvillo's project, In the Air, aims “to make visible the microscopic and invisible agents of Madrid’s air (gases, particles, pollen, diseases, etc.), to see how they perform, react and interact with the rest of the city.” To do this Calvillo and her team mixed bright, organic paint tints with water vapors and released them into Madrid’s air; in effect, they have made a mechanical prototype of an atmosphere, which they call a “diffuse façade.” Calvillo's goals, as the project develops, are to explore how these diffuse facades might operate as an index revealing the particulate content of the air, and more broadly, to render the atmosphere visible to the city's residents. Calvillo's "invisible layers" or "diffuse facades" might also be integrated into the actual facades of buildings, in this way "blurring architecture with atmosphere." [2]

There are, of course, potential hazards with this sort of visualization. It might become confusing, a mass of undecipherable information that a viewer can’t easily sort through. It might also become merely an aesthetic spectacle — a razzle-dazzle data performance sans political meaning or artistic depth. And no matter the goals of the designers, information that unexpectedly becomes visible can be politically suspect — unclear in its motives and methods. Its persuasive capabilities can be elusive as well as treacherous. But Calvillo hopes to empower public health activists who seek to verify or disprove air quality claims made by interests ranging from the state to corporations.

When viewed formally, as architectural spaces of uncertain shape, Calvillo's clouds are part of a contemporary trend, and bring to mind other architectural experiments, most famously the Blur Building, created by Diller Scofidio + Renfro for the Swiss Expo 2002. That project, an "architecture of atmosphere," in the designers' term, challenged the materiality and permanence of conventional construction, using a misting-nozzle "smart weather" system that responded to changing atmospheric conditions. Although, like most expo projects, the Blur was a temporary structure, it worked largely in the tradition of the architecture project of a certain scale, and its atmospheric element — its blur — is conceived and experienced as a monolithic unit, in contrast to the “invisible layers” of Calvillo's In the Air.

Another building conceptualized as a response to its atmospheric environment is the B_mu, a museum project in Bangkok, by the Paris-based architecture practice R&Sie(n). Never built, the radical project, which has achieved a kind of cult status, consists of a stack of rectilinear gallery spaces wrapped in a drooping shroud coated with an electromagnetic material that would attract particles from the polluted city air, much the way the screen of a computer monitor attracts dust. The project drew inspiration from Man Ray’s 1920 Dust Breeding (Duchamp’s Large Glass with Dust Notes), a long-exposure photograph of dust collecting on Duchamp's The Large Glass. As envisioned by the architects, the museum would, with time, become fuzzy and sooty. In this sense R&Sie(n) wanted to harvest the air itself. Yet much like the Blur Building, the project remains conventional in program, organization and scale — and even the social meaning of the pollution itself remains unclear and thus unchallenged. Cocooned in the climate-controlled museum, visitors would have been literally protected — and politically distanced — from the complex networks of relations that enabled the pollution in the first place.

New Airscapes

Given the social provocations of In the Air, even recent projects like Blur and B_mu seem increasingly to belong to an early generation of air design that replicated customary scales of architectural work. Calvillo’s work opens up something new, something that might eventually allow users to “make” new atmospheres based on diverse personal or group agendas. Her sights are set on transforming the smallest pieces of architectural form, what she calls "the microscopic agents that are with us" — spaces that we are often unaware of, but which are everywhere.

Architectural historian David Gissen has written powerfully about the challenge of how to use and to avoid one type of air: smoke. In his book Subnature and on his website, Gissen has speculated about what it might mean to reconstruct the soot-filled air that once dirtied industrial cities like Chicago and Pittsburgh. The goal would not be to re-pollute the city but to create a kind of archive of the older, smoky air, as a way to better understand the industrialization that once defined the experience of living and working in those cities. Gissen has no illusions of actually implementing this proposal. Rather, he wants to critique the increasingly bourgeois, sanitizing goals of the historic preservation movement, and the type and scale of building often chosen for preservation; and he wants to reveal how the presence — or absence — of smoke in the environment can indicate "social rank and the level of command one has over his or her environment." [3]

Another experimentalist historian, the architect Jorge Otero-Pailos, is focusing on historical preservation at a smaller, more domestic scale. Along these lines, he has proposed recreating the smells of cologne and tobacco that once filled the air of the now landmarked Glass House, by Philip Johnson, in New Canaan, Connecticut. Here too, the idea is to make us think about the atmosphere of the place when it was a salon crowded with architects and artists — and smokers — like Mies van der Rohe and Andy Warhol, cluttered with ashtrays and hazy with smoke.

Gissen and Otero-Pailos’s speculations resonate with Calvillo's work, and especially with one of her observations about air: Calvillo has pointed out that when we occupy a space we are inevitably experiencing its accumulated atmosphere. We are inhaling air in the moment, but we are also inhaling air that has lingered, sometimes for a long time. (This becomes especially apparent in sealed-off spaces like basements and attics.) Thus In the Air extrapolates a dreamy urbanism, where atmospheric layers become a kind of mosaic, a perceptible vision, and one moves through fogs of various colors, or even of different smells and perhaps of inebriants that might mentally transport us, as the madeleine transported Proust, to other places or times. (On a related note, Bompas & Parr, architect-producers of what we might call à la carte happenings, concocted a cloud of breathable gin-and-tonics for a London gallery opening in April of 2009.)

The designers of In the Air, on their detailed website, imagine a future when we might all participate in atmospheric creation: "A domestic version of the prototype will be developed. Assembly instructions will be posted on the web and each user will be able to make a unit for their balconies or windows. This will generate a distributed net of visualizations, representing the data collected throughout the city. An individual can “tune” their unit to select the pollutant they are interested in tracking — this will allow for the construction of a collective map of personal environmental interests."

These days we read many claims and assertions about ecology and clean air. What if, as In the Air suggests, we could suspend a plume of tinted air created from years-old data and evaluate it next to a plume created from current data? Has the air improved, or not? Is the particle density greater or lesser? Using In the Air's instruction manual, perhaps one could sift out the air made by a certain polluter, and even re-situate it or blow it into a different location — perhaps toward the polluter’s corporate offices. One could colorize the pollutants that hover over a landscape we are forbidden to enter, like the base at Vieques, with its uranium cloud, so that local residents could identify it from afar. (The base has been demobilized as a “wilderness refuge” — a U.S. government tactic for avoiding the remediation entailed by Superfund designation.) These actions could take air into the realm of political contestation, activating streets and public spaces. But all of this will only be possible when we no longer perceive air as monolithic, singular and static.

In Subnature, Gissen notes that architectural theory and history offer fleeting glimpses of the problem of vapors and dirty air, usually in discussions of chimneys, vents, and other building technologies meant to exhaust smoke from spaces while at the same time retaining the heat and the social pleasure of a hearth fire. Smoke or pollution that contaminates homes, workplaces or entire cities has sometimes signified urban dysfunction or lack of progress, or conversely, modernity and industrialization. Today we are exploring ever more technologically advanced techniques for carbon capture and sequestering, and for using toxic residue like fly ash to make concrete for roads and buildings. Certainly these techniques serve to minimize harmful emissions; they also perhaps reinforce our tendency toward "out of sight, out of mind." In comparison, the projects envisioned by Calvillo, Gissen, Otero-Pailos and others have the opposite aim: to make bad or questionable air visible, part of our perceptible experience, and in this way to make it a real part of our political discussion.

Thursday, October 21. 2010

(sub)Mix: Vibration Sympathique

Electric Fields, the Ottawa-based AV culture biennial festival programmed by our peers at Artengine draws near. The event runs from Nov. 3-7th and one of the participants is Paul Jasen, a PhD candidate researching "low-frequency sonic experience". Paul posted an annotated mix on the Artengine blog in advance of a talk he'll be giving at the festvial and we've reblogged it below.

--

Not sympathy in the sentimental sense. Sympathetic vibration has nothing to do with the personal or emotional. For Helmholtz, it meant transduction of energy, resonance induced in a body – a room, a building, a glass, an eyeball – by an external force. At its resonant, or natural, frequency a body ceases to dampen energy and begins to oscillate with it, amplifying it, even to the point of self destruction.

A 40-minute, sub-centric mix, ahead of my talk (Bass: A Myth-Science of the Sonic Body) at this year’s Electric Fields festival. So much discussion about bass focuses on dancefloor material, so this mix goes the other direction, collecting a series of low-frequency investigations into industrial and earthly hum, pure tones, pipe organs, peculiarities of bodily resonance, and overlapping fictions of sound and signal. Listen loud. To borrow Eleh’s instruction: Volume reveals detail.

MP3: DOWNLOAD (320kbps / 95Mb)

TRACKS & NOTES:

Demdike Stare ‘Suspicious Drone’ (Modern Love)

“…a dense 6 minute opening that chugs along like a malfunctioning mechanical beast, honing in on Lancashire’s dark industrial landscapes.” Following on the heels of labels like Mordant Music, Skull Disco and Ghost Box, Demdike Stare wed body-humming sound system sensibilities and (occasional) frenzied percussion, with smatterings of occulture and Radiophonic hauntology.

Bass Communion ‘Ghosts on Magnetic Tape III’ Original and Reconstruction (Headphone Dust)

Unsettling vibrations, voices in the ether. Bass Communion looks for spectral encounters in the crackle and grooves of manipulated 78rpm shellacs, drawing equally on theories of the infrasonic uncanny and the peculiar phenomenon of EVP. Supplemented here with excerpts and Raymond Cass commentary from The Ghost Orchid: An Introduction to EVP (Parapsychic Acoustic Research Cooperative/Ash International)

Thomas Köner ‘Permafrost’ and ‘Nieve Penitentes 2′ (Barooni/Type)

More of the ice than about it, Köner’s geologic drone work would sit well alongside John Duncan’s Infrasound-Tidal, NASA’s Voice of Earth, and the tremor tones of Mark Bain. The theme is The North, but these aren’t field recordings. Instead, Köner builds his glacial terrain from the shimmer of pitch-shifted gongs. Augmented here by a dark piece from Ruth White, the little acknowledged American electronic composer who’d have made good company for Delia Derbyshire and Daphne Oram at the BBC Radiophonic Workshop. ‘Mists and Rains,’ from the 1969 album Flowers of Evil, sets the Baudelaire poem to an electronic windscape.

Eleh ‘Together We Are One’ (Taiga)

Anonymous and secretive, Eleh is a minor sonic fiction unto itself, its album art drawing on the retina-skewing experiments of Op Art while minimal sleeve notes give faint clues to method and aims. Titles of the first three releases – Floating Frequencies/Intuitive Synthesis volumes I-III – would seem to sum up the project, reputedly based on the layering of outputs from aging audio test oscillators. Subsequent releases Homage to the Square Wave and Homage to the Sine Wave, along with track names like ‘Pulsing Study Of 7 Sine Waves’ (parts 1 & 2), ‘Phase Two: Bass Pulse In Open Air,’ and ‘Linear To Circular / Vertical Axis,’ are nods to both the minimalist tradition and a clinically empiricist attitude toward sonic investigation. But others – ‘In The Ear Of The Gods,’ ‘Phase One: Sleeps Golden Drones Again’ – show a mystical side that revels in the autopoietic strangeness of the subbass encounter.

Nate Young ‘Under the Skin’ (iDeal Recordings)

If Eleh finds the mystical in impersonal vibration, Nate Young’s Regression is the sound of signal possessed, angry, and on the move. ‘Under the Skin’ is a churning slog – submerged in a liquid-matter mush, broken occasionally by a taught screech, before resuming its subcutaneous march.

Sunn o))) ‘Sin Nanna’ (Southern Lord)

Metal with bass weight, indebted to the gravity-enhancing sounds of Earth. ‘Sin Nanna’ is a largely guitar-free interlude, gutteral chanting like the nightmare version of new-agey Gregorian revival. Elsewhere, 2008′s Dømkirke had the band pulling ungodly rumbles from the massive 16th century organ at Rokslide Cathedral, Norway.

Christian Fennesz plays Charles Matthews ‘Amoroso’ (Touch)

And into the light… A 7″ offshoot of Touch Record’s ongoing Spire project (below) which focuses on organ-based and organ-inspired works. 2300 years on, the pipe organ still mystifies. An acoustic synthesizer, one of the earliest machines, it’s clearly been designed to direct force at the body as well as emit musical notes. “Audible at five miles, offensive at two, and lethal at one,” was the contemporary description of the 10th century organ at Winchester said to require 70 men to operate its bellows. Note the mastering credit on this release: Jason Goz at Transition Studios – the name attached to virtually every foundational dubstep release between 2003 and 2006; dubcutter for Jah Shaka, Mickey Finn, Grooverider, DJ EZ, Mala, Loefah, kode9… London bass flows through Transition.

BJNilsen ‘La Petite Chapelle – Rue Basses’ (Touch)

An excerpt from Spire: Live in Geneva Cathedral, Saint Pierre (2005). From the notes: “In a duet with himself, BJNilsen moved back and forth between organ and electronics. He established a link between the old sound inherited from centuries past and a new one being instantly generated. The organ sound was decomposed and in a way, tortured, in order to get at the core of the sound… BJNilsen’s piece ended with a background organ sound, as if to remind us that after all, even if altered, the organ had remained the core of the entire concept.”

Paul Jasen is a PhD candidate in Cultural Mediations at Carleton University. His research focuses on low-frequency sonic experience. He also DJs under the names Autonomic and Mr. Bump. Writing and mixes at Deeptime.net & Riddim.ca.

Personal comment:

Something for us... possibly in relation with Circuit.

Although we missed it yesterday (thanks Joel Vacheron for the pointer nonetheless), this link to an evening at the LUFF with Michael Gendreau that was probably interesting...

Venice Biennale 2010 - The Dutch pavilion

Via WMMNA

-----

By bringing the focus of their exhibition on the thousands of buildings that remain unoccupied in The Netherlands, the Dutch Pavilion puts an ironic twist on "People meet in architecture", the theme of the ongoing Architecture Biennial in Venice.

Even the building where the exhibition takes place has been empty for over 39 years since its inauguration in 1954. The Dutch Pavilion -just like any of the pavilions of the giardini- is indeed open for just a few months per year.

Rietveld Landscape, the office appointed by the Netherlands Architecture Institute (NAI) as curators, has emphasized the vacancy of the pavilion by leaving the ground floor of the pavilion completely empty. Only by walking the stairs up to the mezzanine can the visitor discover that what looked like a foam blue ceiling is in fact a suspended landscape made of the models of vacant lighthouses, schools, water towers, factories, hangars, offices, etc.

A 'placebook' on the wall shows the connections that could between vacant buildings and creative professionals:

The exhibition Vacant NL is a call for the intelligent reuse of temporarily vacant buildings around the world in promoting creative enterprise.

Vacant NL, where architecture meets ideas is not only an appeal to creative talents to exploit the value hidden in society but also unsolicited advice to countries who want to advance up the table of global knowledge economies but don't know where they can find the hidden strengths. The transition to a creative knowledge economy demands specific spatial conditions. Offering young talents from the creative, technology and science sectors an affordable place where they can share their knowledge, creativity and networks is a way of promoting mutual influences, enterprise and innovation. Vacant NL, where architecture meets ideas shows how architecture can contribute to tackling major social problems.

Project Team for the pavilion: Curator Rietveld Landscape worked with Jurgen Bey (designer), Joost Grootens (graphic designer), Ronald Rietveld (landscape architect), Erik Rietveld (philosopher/economist), Saskia van Stein (NAI curator), Barbara Visser (visual artist).

Previously: Architecture Biennale in Venice - The Belgian pavilion.

The Venice Biennale of Architecture runs until 21st November, 2010.

Related Links:

fabric | rblg

This blog is the survey website of fabric | ch - studio for architecture, interaction and research.

We curate and reblog articles, researches, writings, exhibitions and projects that we notice and find interesting during our everyday practice and readings.

Most articles concern the intertwined fields of architecture, territory, art, interaction design, thinking and science. From time to time, we also publish documentation about our own work and research, immersed among these related resources and inspirations.

This website is used by fabric | ch as archive, references and resources. It is shared with all those interested in the same topics as we are, in the hope that they will also find valuable references and content in it.