Via Places via Archinect

-----

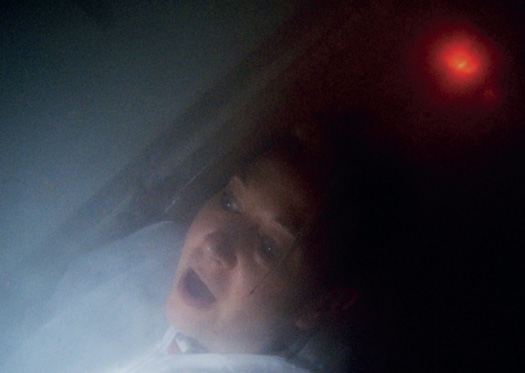

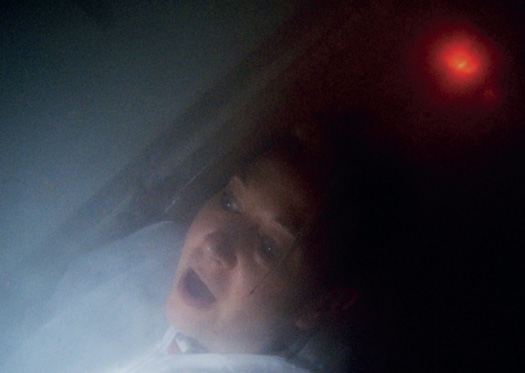

Bompas & Parr: Alcoholic Architecture, 2009. [Photograph: Bompas & Parr. All images courtesy of Air: Alphabet City No. 15]

In late 2009, researchers at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, validated some horrifying claims: 24 slaughterhouse workers from two states had reported symptoms ranging from numbness to paralysis. What all the claims had in common was the workers' location at or near the “head table” in pork processing plants where pig heads are butchered. Investigations revealed that the workers had inhaled a mist of pig brains, and that this had in turn triggered an auto-immune response, causing neurological disorders. This was not only disgusting; it was also a surprise to scientists to learn that “aerosolized” pig brains, the microscopic industrial byproduct of mechanically blowing out every last piece of flesh from a pig's head, can impair the motor functions of anyone who breathes them in.

Perhaps it shouldn't have been a surprise. Almost a century ago, the air we breathe was first understood to be, potentially, a weapon — an innovation that was, like so many innovations, born in warfare, and which marked a turning point for the modern mind. So argues German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk in Terror from the Air, his exploration of the rise of environmental warfare, starting with the German army's deployment of chlorine gas against French and Canadian soldiers at the battle of Ypres in 1915. [1] With the invention of poison gas, the air itself — the imperceptible atmosphere that surrounds us — could be activated, differentiated and unleashed as a killer — as a kind of anti-air. It could be weaponized, and as such used against civilian as well as military populations, a latent concern that became newly pressing in the post-Sept. 11 autumn of 2001 when somebody, most likely a scientist in an American army lab, sent packets of anthrax spores though the U.S. mail, killing five people and infecting seventeen others who breathed in the dust that became airborne when they opened the envelopes.

As architecture theorist Enrique Ramírez has noted, on his site, aggregat456.com, all airborne attacks — he traces a line from the U.S Army's Chemical Warfare Service in Japan during World War II to the 1995 sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway, attributed to the Aum Shinrikyo cult — take malign advantage of the diffusing properties of the air, and of the workings of our pulmonary systems, which deliver the oxygen our bodies need to live. Indeed, the history of weaponized air is long and sometimes macabre. For the past couple of decades — to cite just one more example — the U.S. military has been contaminating otherwise safely breathable air by shooting uranium-tipped bullets. When fired, the bullets become extremely hot, which enables them to pierce armored tanks. Such bullets have been used on battlefields from Kosovo to Baghdad, and also on bases such as the former practice range at Vieques, Puerto Rico. They leave a barely detectable plume in their wake, polluting the air and exposing local civilians to the dangers of radioactivity.

Nerea Calvillo, In the Air, 2008.

Air in Art and Architecture

Aerosolized pig brains and various forms of weaponized air suggest we have underestimated the presence of air, and what it can potentially do. Whatever the spur, we need to take seriously the materiality of air. And today, in fact, a growing number of artists and architects are engaging air in new ways. They are exploring air as a design component, studying how airborne particles can be manipulated into various textures, surfaces and spaces. They are transforming the scales at which architects typically work. And they are bringing the multiple temporalities of air into play through designs that actually collect and archive air from different times. This work could bring about a new consciousness and perhaps an expanded understanding of the meaning of a public architecture — an effort to reclaim the air from those who've attempted to control it in irresponsible and dangerous ways.

Some of the designers who have begun this reclamation project use whimsical strategies, experimenting with tints, adhesives, odors, vapors and other airborne media to harness the latent architectural possibilities of our atmosphere. Especially notable is the work of the Madrid architect Nerea Calvillo, who refers to urban air as “invisible layers that also are landscapes,” and who has worked with a multidisciplinary team to investigate and reveal the hidden or less apparent geographies of cities. Calvillo's project, In the Air, aims “to make visible the microscopic and invisible agents of Madrid’s air (gases, particles, pollen, diseases, etc.), to see how they perform, react and interact with the rest of the city.” To do this Calvillo and her team mixed bright, organic paint tints with water vapors and released them into Madrid’s air; in effect, they have made a mechanical prototype of an atmosphere, which they call a “diffuse façade.” Calvillo's goals, as the project develops, are to explore how these diffuse facades might operate as an index revealing the particulate content of the air, and more broadly, to render the atmosphere visible to the city's residents. Calvillo's "invisible layers" or "diffuse facades" might also be integrated into the actual facades of buildings, in this way "blurring architecture with atmosphere." [2]

There are, of course, potential hazards with this sort of visualization. It might become confusing, a mass of undecipherable information that a viewer can’t easily sort through. It might also become merely an aesthetic spectacle — a razzle-dazzle data performance sans political meaning or artistic depth. And no matter the goals of the designers, information that unexpectedly becomes visible can be politically suspect — unclear in its motives and methods. Its persuasive capabilities can be elusive as well as treacherous. But Calvillo hopes to empower public health activists who seek to verify or disprove air quality claims made by interests ranging from the state to corporations.

Top: Nerea Calvillo, In the Air. 2008. Bottom: Diller + Scofidio, Blur pavilion, 2002.

When viewed formally, as architectural spaces of uncertain shape, Calvillo's clouds are part of a contemporary trend, and bring to mind other architectural experiments, most famously the Blur Building, created by Diller Scofidio + Renfro for the Swiss Expo 2002. That project, an "architecture of atmosphere," in the designers' term, challenged the materiality and permanence of conventional construction, using a misting-nozzle "smart weather" system that responded to changing atmospheric conditions. Although, like most expo projects, the Blur was a temporary structure, it worked largely in the tradition of the architecture project of a certain scale, and its atmospheric element — its blur — is conceived and experienced as a monolithic unit, in contrast to the “invisible layers” of Calvillo's In the Air.

Another building conceptualized as a response to its atmospheric environment is the B_mu, a museum project in Bangkok, by the Paris-based architecture practice R&Sie(n). Never built, the radical project, which has achieved a kind of cult status, consists of a stack of rectilinear gallery spaces wrapped in a drooping shroud coated with an electromagnetic material that would attract particles from the polluted city air, much the way the screen of a computer monitor attracts dust. The project drew inspiration from Man Ray’s 1920 Dust Breeding (Duchamp’s Large Glass with Dust Notes), a long-exposure photograph of dust collecting on Duchamp's The Large Glass. As envisioned by the architects, the museum would, with time, become fuzzy and sooty. In this sense R&Sie(n) wanted to harvest the air itself. Yet much like the Blur Building, the project remains conventional in program, organization and scale — and even the social meaning of the pollution itself remains unclear and thus unchallenged. Cocooned in the climate-controlled museum, visitors would have been literally protected — and politically distanced — from the complex networks of relations that enabled the pollution in the first place.

New Airscapes

Given the social provocations of In the Air, even recent projects like Blur and B_mu seem increasingly to belong to an early generation of air design that replicated customary scales of architectural work. Calvillo’s work opens up something new, something that might eventually allow users to “make” new atmospheres based on diverse personal or group agendas. Her sights are set on transforming the smallest pieces of architectural form, what she calls "the microscopic agents that are with us" — spaces that we are often unaware of, but which are everywhere.

David Gissen, Reconstruction: Smoke. 2006–2010.

Architectural historian David Gissen has written powerfully about the challenge of how to use and to avoid one type of air: smoke. In his book Subnature and on his website, Gissen has speculated about what it might mean to reconstruct the soot-filled air that once dirtied industrial cities like Chicago and Pittsburgh. The goal would not be to re-pollute the city but to create a kind of archive of the older, smoky air, as a way to better understand the industrialization that once defined the experience of living and working in those cities. Gissen has no illusions of actually implementing this proposal. Rather, he wants to critique the increasingly bourgeois, sanitizing goals of the historic preservation movement, and the type and scale of building often chosen for preservation; and he wants to reveal how the presence — or absence — of smoke in the environment can indicate "social rank and the level of command one has over his or her environment." [3]

Another experimentalist historian, the architect Jorge Otero-Pailos, is focusing on historical preservation at a smaller, more domestic scale. Along these lines, he has proposed recreating the smells of cologne and tobacco that once filled the air of the now landmarked Glass House, by Philip Johnson, in New Canaan, Connecticut. Here too, the idea is to make us think about the atmosphere of the place when it was a salon crowded with architects and artists — and smokers — like Mies van der Rohe and Andy Warhol, cluttered with ashtrays and hazy with smoke.

Gissen and Otero-Pailos’s speculations resonate with Calvillo's work, and especially with one of her observations about air: Calvillo has pointed out that when we occupy a space we are inevitably experiencing its accumulated atmosphere. We are inhaling air in the moment, but we are also inhaling air that has lingered, sometimes for a long time. (This becomes especially apparent in sealed-off spaces like basements and attics.) Thus In the Air extrapolates a dreamy urbanism, where atmospheric layers become a kind of mosaic, a perceptible vision, and one moves through fogs of various colors, or even of different smells and perhaps of inebriants that might mentally transport us, as the madeleine transported Proust, to other places or times. (On a related note, Bompas & Parr, architect-producers of what we might call à la carte happenings, concocted a cloud of breathable gin-and-tonics for a London gallery opening in April of 2009.)

Bompas & Parr, Alcoholic Architecture. 2009.

The designers of In the Air, on their detailed website, imagine a future when we might all participate in atmospheric creation: "A domestic version of the prototype will be developed. Assembly instructions will be posted on the web and each user will be able to make a unit for their balconies or windows. This will generate a distributed net of visualizations, representing the data collected throughout the city. An individual can “tune” their unit to select the pollutant they are interested in tracking — this will allow for the construction of a collective map of personal environmental interests."

These days we read many claims and assertions about ecology and clean air. What if, as In the Air suggests, we could suspend a plume of tinted air created from years-old data and evaluate it next to a plume created from current data? Has the air improved, or not? Is the particle density greater or lesser? Using In the Air's instruction manual, perhaps one could sift out the air made by a certain polluter, and even re-situate it or blow it into a different location — perhaps toward the polluter’s corporate offices. One could colorize the pollutants that hover over a landscape we are forbidden to enter, like the base at Vieques, with its uranium cloud, so that local residents could identify it from afar. (The base has been demobilized as a “wilderness refuge” — a U.S. government tactic for avoiding the remediation entailed by Superfund designation.) These actions could take air into the realm of political contestation, activating streets and public spaces. But all of this will only be possible when we no longer perceive air as monolithic, singular and static.

In Subnature, Gissen notes that architectural theory and history offer fleeting glimpses of the problem of vapors and dirty air, usually in discussions of chimneys, vents, and other building technologies meant to exhaust smoke from spaces while at the same time retaining the heat and the social pleasure of a hearth fire. Smoke or pollution that contaminates homes, workplaces or entire cities has sometimes signified urban dysfunction or lack of progress, or conversely, modernity and industrialization. Today we are exploring ever more technologically advanced techniques for carbon capture and sequestering, and for using toxic residue like fly ash to make concrete for roads and buildings. Certainly these techniques serve to minimize harmful emissions; they also perhaps reinforce our tendency toward "out of sight, out of mind." In comparison, the projects envisioned by Calvillo, Gissen, Otero-Pailos and others have the opposite aim: to make bad or questionable air visible, part of our perceptible experience, and in this way to make it a real part of our political discussion.