Wednesday, October 27. 2010

Via GOOD

-----

by Alex Goldmark

Sometimes you can take two problems, add them together, and get a win-win solution. In this case, here are the two problems: First, as cities expand we create more waste and more sewage, and we don’t have any really good plan for it. And second, we keep making more and more plastic that never goes away, filling landfills or swimming in oceanic garbage patches. So, what’s the natural solution? Why not turn the poop into plastic that biodegrades? Simple, right? Actually, yes. It turns out it is.

Ryan Smith is CTO of Micromidas, and he turns poop into plastic for a living. “We take raw sewage from a waste water treatment plant and we convert it to biodegradable plastic.” He says it is “just a series of tanks, nothing complicated or fancy about it. Nothing that is technically too difficult.” That’s because he gets bacteria to do the hard work for him, and that’s the novelty of his product. Finding the bacteria, and mixing them up into the right combination, that’s a different story.

Right now, most plastic comes from petroleum. So as you tear open that new SD card from its packaging, or toss out the packing foam from your last Amazon order, you are, in essence consuming oil. There are various sugar- or corn-based bioplastics on the market already. (You can even follow this You Tube video and try to make your own.) These starch-based plastics solve the problem of living forever in a landfill or garbage patch, but if produced at the volume of petro-plastic, they would significantly drive up the price of corn or sugarcane. So a better solution, and the innovation here, is that Micromidas’ bioplastic adds sewage treatment to the enviro-benefits, and leaves corn out of the mix. It just so happens that’s also good for the bottom line.

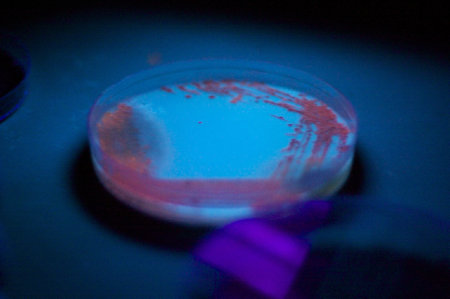

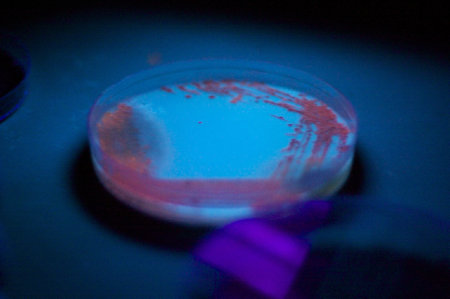

(Dane Anderson Micromidas Engineer at work)

Here’s how it works, as explained by Smith. They take sewage and feed it to bacteria. “The bacteria store the organics as a bio-polymer … little plastic granules, or inclusions, inside their bodies … they are creating it.” Just like when we eat sugar and, through a series of metabolic processes, turn that into a fat, those little micro-buggers turn sewage into plastic in their bodies.

Then Micromidas uses a proprietary process that "disrupts" the cells and takes the plastic out. After they get it all cleaned up, the end product is a high-value, low-cost plastic resin ready to be sold off, and it biodegrades in under 18 months once disposed of.

Lest you go try this at home, the bacteria are no ordinary bottom-of-your-tub household contagions. Ryan Smith says, “we actually have bug hunters, or ecological microbiologists. They actually go out into nature, they grab a soil sample, a sample of pond water, a sample of waste water” and then through a series of screening mechanisms they pick out just the right microbes that are particularly good at consuming sewage and making bio-plastic.

The company then breeds and combines the best of these and now has a library of 50-60 bacteria with different traits for different kinds of sewage chomping and plastic pooping depending on the needs of the “feed source.” Yes, that’s another way of saying, there is a secret formula of bacteria that eat poop and poop plastic, and it varies depending on the sewage you want to feed them—that’s the business in a nutshell.

Technically speaking, what the bacteria create inside their bodies is a resin powder. Its not a final product by a long shot. Micromidas then has to sell that to a plastics processor. Smith concedes, “we are not currently at a point where we know for certain what application makes the most sense.” Over the past couple months they have developed enough of the plastic resin to send to testing labs to explore options. Possible final products currently being prototyped and tested could be foams, fibers, films, injection molds and lots of other fancy words that mean plastic packaging that doesn’t get anywhere near food. “Something you don’t eat with, but is a packaging material, and ecologically beneficial,” Smith says.

If he can prove his resin does the job, the economics are in his favor. For most plastics, the “feed stock” is about 50 percent of the production cost, whether it's petroleum or bioplastic, but in this case Micromidas actually gets paid to take the sewage off the hands of local processing plants. That’s starting production with a negative unit cost. Not a bad sign for sustainability.

Right now they are still paying for the heavy load of research, testing, and other start-up costs, but Smith says he’s expecting to make his bioplastic at competitive market prices for other disposable plastics when they finalize the formula.

They plan to build out their operation to a commercial scale (right now its prototype scale) within the next six to twelve months he says. Then the money, and the poop will roll in.

Images courtesy of Micromidas.

Monday, October 25. 2010

Via Mashable

-----

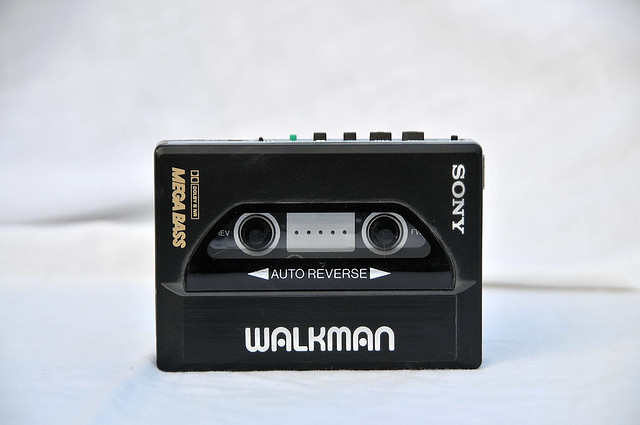

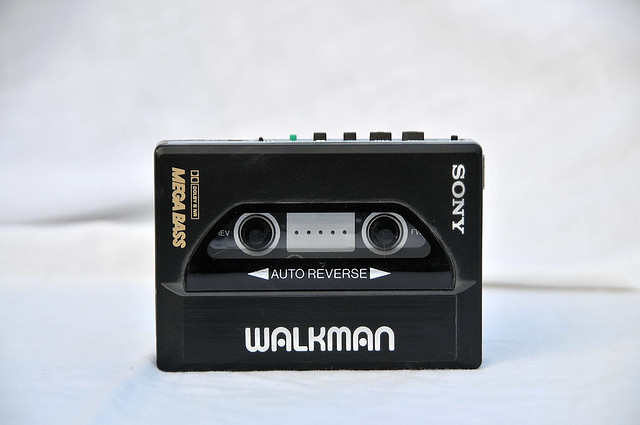

After retiring the floppy disk in March, Sony has halted the manufacture and distribution of another now-obsolete technology: the cassette Walkman, the first low-cost, portable music player.

The final batch was shipped to Japanese retailers in April, according to IT Media. Once these units are sold, new cassette Walkmans will no longer be available through the manufacturer.

The first generation Walkman (which was called the Soundabout in the U.S., and the Stowaway in the UK) was released on July 1, 1979 in Japan. Although it later became a huge success, it only sold 3,000 units in its first month. Sony managed to sell some 200 million iterations of the cassette Walkman over the product line’s 30-year career.

Somewhat ironically, the announcement was delivered just one day ahead of the iPod’s ninth anniversary on October 23, although the decline of the cassette Walkman is attributed primarily to the explosive popularity of CD players in the ’90s, not the iPod.

Personal comment:

R.I.P. the "cassette walkman". I thought it was already gone for years! Now this is the occasion to light up a candle.

-----

Remember the movie Lawnmower Man? Here's why we're not even close.

The early 90's were awesome. Bill Watterson was still drawing Calvin and Hobbes, the tattered remnants of the Cold War were falling down around our ears, and most of Wall Street was convinced the Macintosh was a computer for effete graphic designers and Apple was more or less on its way out.

Into this time of innocence came a radical vision of the future, epitomized by the movie Lawnmower Man. It was a future in which Hollywood starlets had virtual intercourse with developmentally challenged computer geeks in Tron-style bodysuits and everything looked like it was rendered by a Commodore Amiga.

Anyway, at that time Virtual Reality was a Big Deal. Jaron Lanier, the computer scientist most closely associated with the idea, was bouncing from one important position to another, developing virtual worlds with head mounted displays and, later, heading up the National Tele-immersion initiative, "a coalition of research universities studying advanced applications for Internet 2," whatever the heck that was.

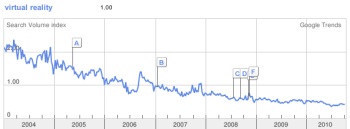

|

Google Trend shows the steady decline in searches for "Virtual Reality" |

Even so, some sensed that the technology wasn't bringing about the revolution that had been promised. In a 1993 column for Wired that earns a 9 out of 10 for hilarity and a 2 out of 10 for accuracy, Nicholas Negroponte, founder of the MIT Media Lab (who I'm praying will have a sense of humor about this) asked the question that was on everyone's mind: Virtual Reality: Oxymoron or Pleonasm?

It didn't matter if anyone knew what he was talking about, because time has proved most of it to be nonsense:

"The argument will be made that head-mounted displays are not acceptable because people feel silly wearing them. The same was once said about stereo headphones. If Sony's Akio Morita had not insisted on marketing the damn things, we might not have the Walkman today. I expect that within the next five years more than one in ten people will wear head-mounted computer displays while traveling in buses, trains, and planes.... One company, whose name I am obliged to omit, will soon introduce a VR display system with a parts cost of less than US$25."

Affordable VR headsets were just around the corner, really? And the only real barrier to adoption, according to Negroponte? Lag. Computers in 1993 just weren't fast enough to react in real time when a user turned his or her head, breaking the illusion of the virtual.

According to Moore's Law, we've gone through something like 10 doublings of computer power since 1993, so computers should be about a thousand times as powerful as they were when this piece was written - not to mention the advances in massively parallel graphics processing brought about by the widespread adoption of GPUs, and we're still not there.

So what was it, really, that kept us from getting to Virtual Reality?

For one thing, we moved the goal posts - now it's all about augmented reality, in which the virtual is laid over the real. Now you have a whole new set of problems - how do you make the virtual line up perfectly with the real when your head has six degrees of freedom and you're outside where there aren't many spatial referents for your computer to latch onto?

And most important of all, how do you develop screens tiny enough to present the same resolution as a large computer monitor, but in something like 1/400th the space? This is exactly the problem that has plagued the industry leader in display headsets, Vuzix. Their products are fine for watching movies, but don't try using them as a monitor replacement.

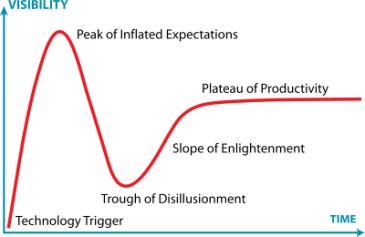

Consumer-level Virtual Reality, it turns out, is really, really hard - not quite Artificial Intelligence hard, but so much harder than anyone expected that people just aren't excited anymore. The Trough of Disillusionment on this technology is deep and long.

That doesn't mean Virtual Reality is gone forever - remember how many false starts touch computing had before technologists succeeded with, of all things, a phone?

And, just a coda, even though the public long ago gave up on searching for Virtual Reality, the news media never got tired of it. Which just shows you how totally out of touch we can be:

Monday, October 18. 2010

Via Transmaterial

-----

FEATURE, WOOD— BY BLAINE BROWNELL ON OCTOBER 15, 2010 AT 9:00 AM

The result of an experimental four-month collaboration with an aerospace machinery manufacturer, the fluid form of Paul Loebach’s Shelf Space pushes the limits of wood engineering and advanced machining technology. There have been vast developments in the evolution of CNC-machining technology in the last thirty years, and this product applies sophisticated modern manufacturing techniques to a traditional renewable material.

Shelf Space is made from a stack lamination of solid wood, cut into shape using a multiaxis milling machine normally used for machining aerospace parts. The decorative form is inspired by the language of eighteenth-century woodworking and the shape—nearly impossible to create with conventional tools—is designed to broaden one’s expectations of what can be called “traditional.”

Three-dimensional computer modeling facilitated the design of a precise yet fluid form. Although it took months to perfect the programming of the complex tool path, due to the incredible power of the machinery each shelf can now be made in just twenty minutes.

Click here for more information.

Personal comment:

To follow our recent post about Troika's last installation and to stay in an "ornemental" context, Shelf Space is another experiment in the direction of digital fabrication. decorative "digital detailing" in this case...

Friday, October 08. 2010

Via TFTS

Whilst few (and especially Apple) would refute that HTML5 is the future of the web (Apple, you may recall, see HTML5 as an outright replacement for Abobe’s Flash – not that Adobe are not opening embracing the HTML5 standard themselves) it seems HTML5 is still not ready for full web deployment as the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) have confirmed that they are running into interoperability issues meaning its not yet ‘ready for production’.

“The problem we’re facing right now is there is already a lot of excitement for HTML5, but it’s a little too early to deploy it because we’re running into interoperability issues,” says W3C’s Philippe Le Hegaret. “The real problem is can we make [HTML5] work across browsers and at the moment, that is not the case.”

This standpoint has been further backed up by industry analyst Al Hilwa (IDC) who highlights that, to date, mainstream browsers (not withstanding betas) are still not yet where they need to be for when the new standard hits. “HTML 5 is at various stages of implementation right now through the Web browsers. If you look at the various browsers, most of the aggressive implementations are in the beta versions,” Hilwa observes. “IE9 (Internet Explorer 9), for example, is not expected to go production until close to mid-next year. That is the point when most enterprises will begin to consider adopting this new generation of browsers.”

Interestingly, as an aside, whilst Hegaret sees HTLM5 as a ‘game changer’ and doesn’t doubt that HTLM5 will impact on the use of Abobe’s Flash on websites once the new standard is wholly adopted (HTML5 features integrated support for video and Canvas 2D) he still sees a place for both Flash and other comparable technologies (Microsoft’s Silverlight, for example) whilst Apple’s stance is, as alluded to previously, somewhat more hardline on this issue – if you need insight into Apple’s (in particular Jobs’) stance on the matter you can read more here or you can scroll down to the related posts section for yet more reading on the subject.

“We’re not going to retire Flash anytime soon,” says Hegaret who adds that “”You will see less and less websites using Flash” as HTML5 becomes the standard for website development.

So, quite when can we expect to see HTML5, which initially began development in 2004, hit the open web and become the de facto standard for web development? It seems that we are still looking at the 2 to 3 year timeframe though Hegaret has confirmed that the standard should be ‘feature-complete’ by the middle of next year.

|