Tuesday, January 05. 2010

The movie titled "Known Universe" takes viewers from the Himalayas through our atmosphere and the inky black of space to the afterglow of the Big Bang. Every star, planet, and quasar seen in the film is possible because of the world's most complete four-dimensional map of the universe, the Digital Universe Atlas that is maintained and updated by astrophysicists at the American Museum of Natural History.

Every satellite, moon, planet, star and galaxy is represented to scale and its correct, measured location according to the best scientific research to-date.

Watch the video HERE.

-----

Via Information aesthetics

Ever since Google pushed other search engines such as Yahoo!, Ask Jeeves and Alta Vista out of the water, it has become the jumping off point for any question or query known to connected man, writes Camilla Grey. A quick peek at Google‘s Year End ‘Zeitgeist’ report reveals how much the connected world relies on the service for answers to common issues. And, as the iPhone marketing has recently asserted ‘…there’s an app for that’, insinuating that whatever you need to know, learn, work out, buy and find technology and the internet can help. Great.

But something strange is happening to my brain. Yes, Google helps me work out aspect ratio conversions. Yes, Google told me that Waitrose on Holloway Road opens at 8.30am. But, the other day, when I couldn’t find my favourite pair of earrings, my instinctive response, my first move in solving the problem was to think: ‘I’ll Google where my earrings are.’

So what does this mean? It’s all very well using the internet to solve problems we can’t figure out by ourselves, but the more we use it, the fewer problems we will be able to solve. Our brains, surely, will become less adept at things we’ve always taken for granted, such as remembering names, dates, locations, spellings and sums.

Sounds scary, but evolution is scary. One minute you’re all scuttling around on four legs, huddling in caves for warmth, the next thing you know, your neighbour up the road is towering over you on two legs, warming their hands against a fire and thinking about inventing the wheel.

We’ve taken remembering things for granted because, apart from books and such, we’ve had to. But maybe, as that becomes increasingly unnecessary, think of what we will be able to do with all that extra head space! With petty problem solving and useless memories not such an issue, other parts of our brains, such as our imaginations, can develop and get better. Ray Kurzweil’s vision for The University of Singularity is precisely to harness this opportunity. As they say, ‘With the support of a broad range of leaders in academia, business and government, SU hopes to stimulate groundbreaking, disruptive thinking and solutions aimed at solving some of the planet’s most pressing challenges’. This kind of statement throws into question everything we thought about learning and academia. Even the notion of ‘knowledge’ becomes questionable and possibly irrelevant.

As a member of the generation that bridges the gap between those who grew up with the Internet and those who didn’t, the idea of Googling the location of my earrings feels unnerving. But what about the ankle-biters behind me? A colleague of mine recently watched his child attempt to work a TV using the touch action of an iPhone. The future is snapping at our heels and it’s going to be a case of change, adapt or die.

Eye is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy single issues. Take out a subscription, and get Eye delivered to your door, anywhere in the world.

-----

Via Eye Magazine

Personal comment:

"Free you brain, use Google"?

It's interesting because this "free head space capacity" left by the fact we don't need to remember things anymore reminds me of a conference by Michel Serres I heard a few years ago. He was saying exactly the same thing, comparing it to the time we started to use our hands for something else than to support our own weight on 4 feets. We gain an enormous potential through that single act: freeing our hands from their initial function to discover hundreds of new.

We are now freeing our brain from keeping memory of things. We can use this for something else. Make place now to imagination please!

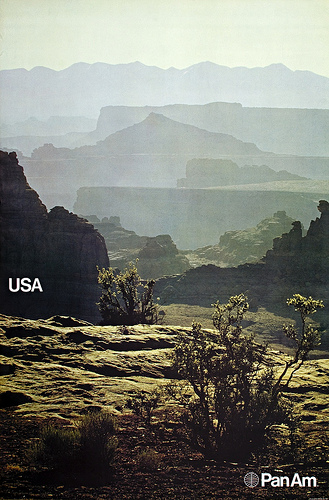

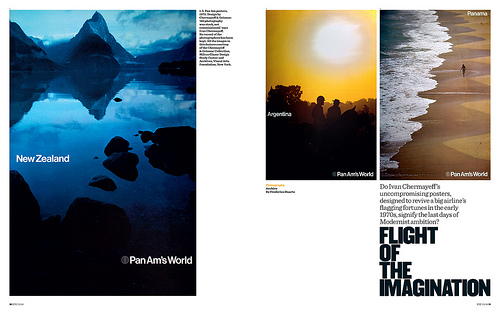

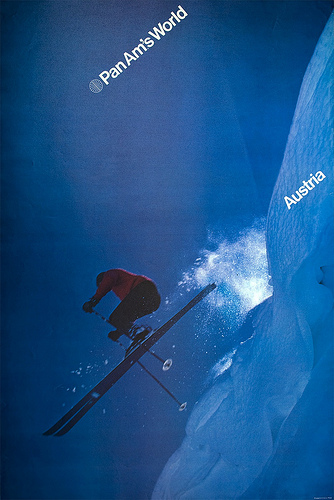

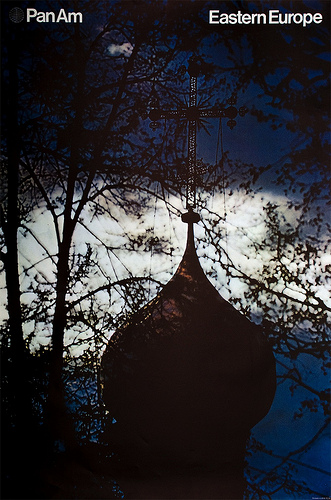

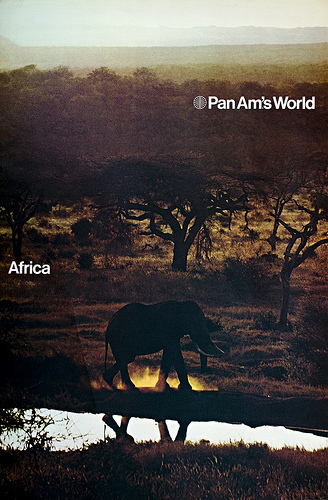

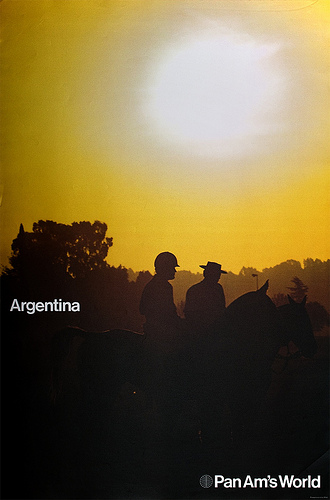

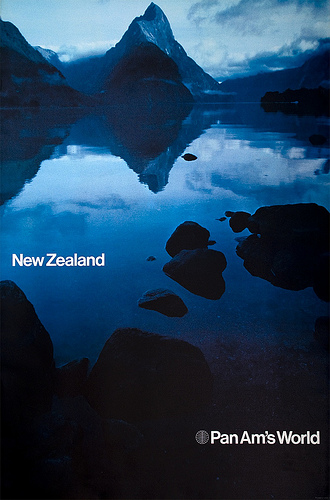

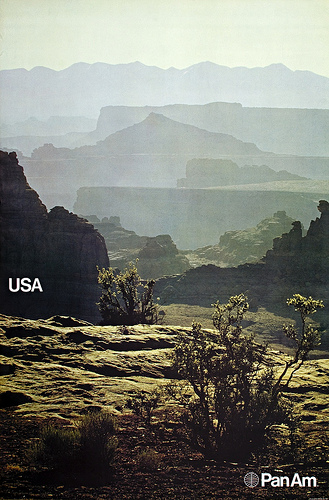

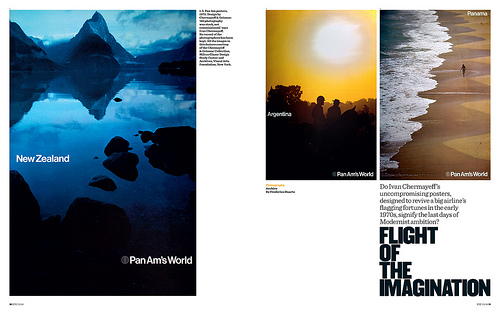

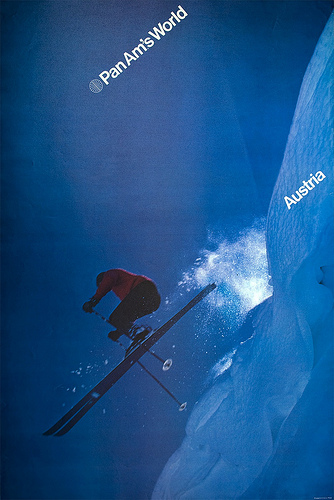

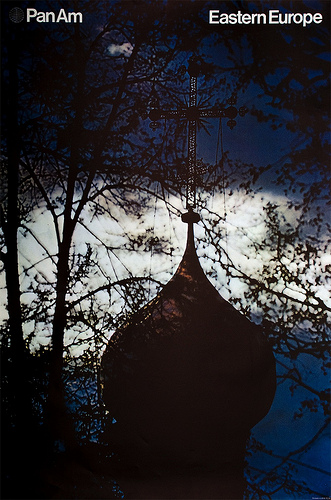

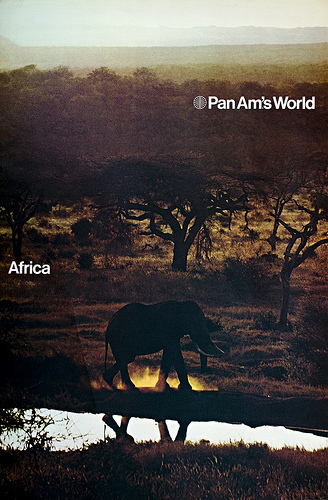

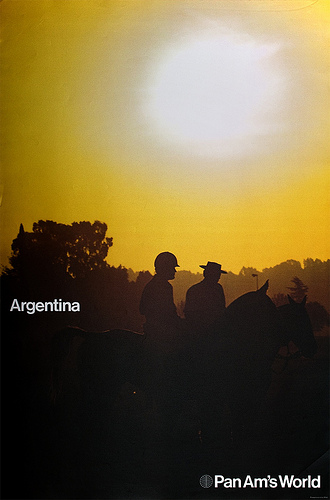

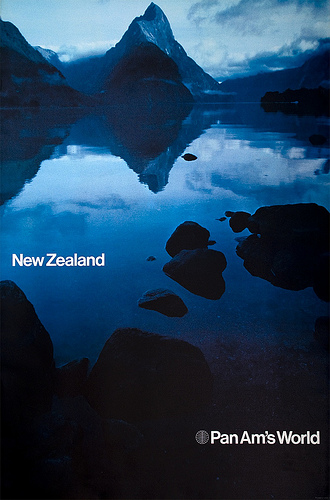

I came across six Pan Am posters while visiting the ‘Here Is Every. Four Decades of Contemporary Art’ exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, writes Frederico Duarte

At the time I was looking for a subject for my ‘Design as Protagonist’ project, part of Steven Heller’s Researching Design class at D-Crit (the MFA in Design Criticism at the School of Visual Arts). Also known as the ‘No Google Class’, this course urges students to find more about a designed object without recurring to Internet search engines, in order to build a narrative around its manufacture, design, application and influence.

When asked if he knew these designs, Heller replied: ‘I don’t know the posters, but would love to know more. It also goes to the heart of how “modern” Pan Am was in its approach to graphics. Worth a book.’ I knew I was on to something.

At MoMA’s Architecture and Design archive, cataloguer Paul Galloway found ‘a whole lot of nothing’ on the posters apart from the 1972 shipping receipts. At the Chermayeff & Geismar (C&G) collection at SVA’s Milton Glaser Design Study Center and Archives, archivist Beth Kleber showed me other posters and materials from that period, which proved MoMA’s six were part of a larger set, but nothing else. I never got a reply from the Pan Am archives at the University of Miami. I simply had to go to the sources to find my answers.

Below: Opening spread from ‘Flight of the imagination’, Frederico Duarte’s article about the Pan Am posters in Eye 73.

What followed could be an experiment on the six-degrees-of-separation theory. On the week I contacted the C&G studio, Michael Bierut told me during his first class he knew the posters and how to reach Bill Sontag, a designer at C&G who worked on them – via Joseph Bottoni, a professor at the University of Cincinatti, Bierut’s alma mater.

I later met with Ivan Chermayeff himself, after speaking on the phone with Bottoni, Sontag and Bruce Blackburn – another designer who worked at C&G and whom MoMA – still – wrongly credits as an author of the Bali poster.

While looking at the posters for the first time in decades (including one which according to him could not have been designed at C&G and was swiftly thrown away), Chermayeff told me a few interesting anecdotes about the redesign, but not the whole story. The same day I met with George Tscherny, who also worked for Pan Am and whose work is also in the SVA archive. He gave me Patrick Friesner’s email and told me to get in touch with him: our correspondence began that evening. Friesner, a Briton now living in northern Dordogne, was at the time – under CEO Najeeb Halaby – Pan Am’s Head of Sales Promotion (not of Sales and Promotion, as I wrongly stated in the article). In his many witty and insightful emails, he revealed to me the fascinating process behind Pan Am’s short-lived Helvetica dream.

But I still wanted to understand how these posters ended up in MoMA. Chermayeff told me he was not involved in the acquisition process, despite being a trustee and consultant at the time. I then wrote to Christian Larsen, who while at MoMA’s A&D department almost included the Hawaii poster in the 2007 Helvetica exhibition he curated. Larsen got me thinking if Mildred Constantine, MoMA’s Associate Curator of Graphic Design from 1943 to 1971, had acquired the Pan Am posters during her last year at the museum, as part of her many other ‘Swiss school’ acquisitions from the likes of Armin Hofmann, Josef Müller-Brockmann, Manfred Bingler, Tomoko Miho and Massimo Vignelli. That would explain why there are no posters from 1972, only from 1971, in the collection (an easy way to tell the date: Logo + Pan Am = 1971, Logo + Pan Am’s World = 1972).

Connie Butler, MoMA’s current Robert Lehman Foundation chief curator of drawings who included the Chermayeff’s posters in an exhibition dedicated to the past 40 years of the museum’s collection, told me on the phone how surprised she was with their success: she got more feedback from fellow curators and artists about them than about any other of the more than 100 works on show.

Then, on the day we handed our research results (in the form of posters and books) to Steven Heller, Emily King visited our department on West 21st Street. While looking at my poster, she said ‘I think Alan Fletcher did work for Pan Am, too.’ Friesner had never mentioned Fletcher, but I also didn’t ask. By then I could finally Google the words “Pan Am Posters”, so I did. Not only I got immediate proof Fletcher had indeed worked for Pan Am, I later learned from Friesner how he got the job – another six-degree-of-separation-story, worthy of its own blog post: think Mad Men with extra air miles.

Another thing I learned from Google was that none of the people running the many Pan Am memorabilia websites, dedicated as they can be, seems to have even heard of these posters. Few have found any of the materials designed between 1971 and 1972. Judging by these sites (or eBay, for that matter) it was as if this redesign never existed.

Pan Am is no longer. But the story of its redesign, as told by the people behind it, proves personal connections, proximity and chance are all makers of (design) history. How many other great design stories are left untold?

You can read Frederico Duarte’s article ‘Flight of the imagination’ on the Eye website and in Eye 73, a photography special issue.

Eye is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop. For a taste of the magazine, try Eye before you buy.

-----

Via Eye Magazine

Personal comment:

I found this old PanAm ad campaign interesting. For many different reasons: both for its quality and nowadays old flavoured "dream destinations". But it tells something to me about the early ages of tourism and globalisation where distant location where still strange, mysterious and "magical". The ad was about that at least, and it sounds now old flavoured isn't it?

In a recent article about Dubai—the world's easiest architectural target, and a city whose only true believers were money launderers and U.S.-based green architecture blogs—Der Spiegel describes the soon-to-open Burj Dubai as "an impressive, supremely elegant edifice."

[Image: The Burj Dubai, photographed by Karim Sahib for the Agence France Press]. [Image: The Burj Dubai, photographed by Karim Sahib for the Agence France Press].

Aside from that remark, however, the magazine is far from complimentary; it includes, for instance, a laundry list of dictatorial building projects around the world (which would encompass, by extension, the Burj Dubai):

President Nursultan Nazarbayev of Kazakhstan had Astana, an entire city of monumental avenues, triumphal arches and pyramids built as his new capital, where marble contrasts with granite, buildings are topped by gigantic glass domes and, on the Bayterek Tower, every subject can place his or her hand in a golden imprint of the president's hand.

In the Burmese jungle, dictatorial generals had an absurd new capital, Naypyidaw, or "Seat of the Kings," conjured up out of nothing. Yamoussoukro, the capital of Côte d'Ivoire and a memorial to the country's now-deceased first president, Félix Houphouët-Boigny, is even a step closer to the brink. The city is filled with grandiose buildings, but there are hardly any people to be seen. The Basilica of Notre Dame de la Paix is a piece of lunacy inspired by the Basilica of St. Peter in the Vatican, but the African church is even bigger than St. Peter's. Indeed, it is the world's largest Catholic church.

From St. Petersburg to Macchu Picchu, the article lays out oblique evidence for an "excessive building of cities and towers" on behalf of people with political clout (and a halo of military protection).

But it is Der Spiegel's continued description of the Burj Dubai that deserves more attention here, in particular this reference to the tower's meteorological variability:

The tower is so enormous that the air temperature at the top is up to 8 degrees Celsius (14 degrees Fahrenheit) lower than at the base. If anyone ever hit upon the idea of opening a door at the top and a door at the bottom, as well as the airlocks in between, a storm would rush through the air-conditioned building that would destroy most everything in its wake, except perhaps the heavy marble tiles in the luxury apartments. The phenomenon is called the "chimney effect."

This takes on atmospherically intriguing possibilities when we read that, on June 6, 2007, "the weather service at the [Dubai] airport e-mailed" to the building's construction director "a satellite image showing a cyclone that had developed over the Indian Ocean, the biggest storm ever recorded in the region, which was heading directly for the Strait of Hormuz. 'That was the only day in five years,' says Hinrichs [the construction director], 'when we had to close the construction site.'"

But, someday, might one negate the other? The Burj Dubai becomes a James Bondian anti-cyclone device: you strategically open certain off-limits doors, with special keys and voice-recognition airlocks, and you park certain elevators at pressure-sensitive sites within their shafts, and soon you're modifying wind-flow over whole minor continents.

A vertical Maginot Line, fluted to control—and even generate—inclement weather.

-----

Via BLDGBLOG

Sun, wind and wave-powered: Europe unites to build renewable energy 'supergrid' [The Guardian]

"It would connect turbines off the wind-lashed north coast of Scotland with Germany's vast arrays of solar panels, and join the power of waves crashing on to the Belgian and Danish coasts with the hydro-electric dams nestled in Norway's fjords: Europe's first electricity grid dedicated to renewable power will become a political reality this month, as nine countries formally draw up plans to link their clean energy projects around the North Sea. The network, made up of thousands of kilometres of highly efficient undersea cables that could cost up to €30bn (£26.5bn), would solve one of the biggest criticisms faced by renewable power – that unpredictable weather means it is unreliable. With a renewables supergrid, electricity can be supplied across the continent from wherever the wind is blowing, the sun is shining or the waves are crashing." Fabulous.

-----

Via City of Sound

|

[Image: The Burj Dubai, photographed by Karim Sahib for the

[Image: The Burj Dubai, photographed by Karim Sahib for the