By James Westcott on ArtReview

Summer is pavilion time, a time for follies. London has a lot of them this season, several of which come courtesy of Portavilion, a new project for putting art in parks. Scattered around London and loosely following the path of the Circle Line are pavilions/sculptures by Dan Graham, Annika Eriksson, Toby Paterson and Monica Sosnowska.

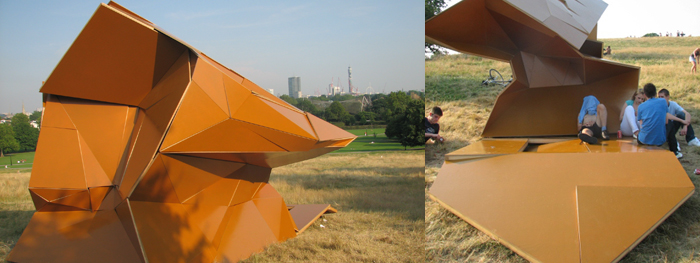

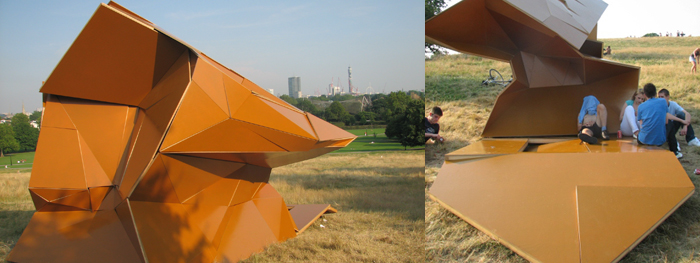

Sosnowska, the Polish archi-sculptor, whose huge and psychologically violent site-specific work shines in her current exhibition at the Schaulager, has plonked a crumpled shed-type structure half way up Primrose Hill, called Wind House, evoking the idea that it might have been viciously sculpted by the wind. The hand behind it is much more exacting and precise than that, creating a pleasingly angular constructivist assemblage of shards that points to the horizon, to the future even.

Monica Sosnowska, Wind House, on Primrose Hill. Photos: James Westcott

What are pavilions for? A utopian prototype for the future (like Le Corbusier's 1924 Pavilion de l'esprit nouveau), architecture with its shackles cast off, a chance for artists to act like architects and program our activities more directly than they otherwise could? Or must pavilions not be for anything in particular, thus giving them their crucial ingredient of duty-free experimentation? Sosnowska's pavilion falls into this latter camp, making no particular demands on (or concessions to) its 'users'. When I visited, it was being used much like a bus shelter by some slouching teenagers hanging out on their school holidays, which is all good – at least the structure is alluring and durable enough to accommodate them.

Toby Paterson, Powder Blue Orthogonal Pavilion, in Potters Fields Parks

Down by the river, between Tower Bridge and City Hall, stands Toby Paterson's Powder Blue Orthogonal Pavilion. It's a serene modernist arrangement of perpendicular planes and surfaces that flicker as you walk by, hiding and revealing the river view and the sky above. It's a bit of a maze, and try as you might to get into it, there is no centre – it never quite encloses you. Like Sosnowska's, this pavilion is for nothing much except lying or playing on, and the lack of functionality is a real gift.

The H Box at Tate Modern

Heading west along the river is the next pavilion stop: H Box at Tate Modern. This isn't a pavilion, strictly speaking, but one can't really speak strictly about pavilions at all. There was a lot of fuss about the H Box, generated by its sponsors Hermès, when it landed on the bridge over the Turbine Hall a few weeks ago. It does indeed look a bit like a spaceship – overdesigned by Didier Fiuza Faustino – and inside it's pleasantly womb-like, but conceptually and aesthetically it's ridiculously overwrought for what is basically a small cinema for showing video art – a lot of it really bad, all of it produced by Hermès. The H Box is on a perpetual world tour of museums, and has a slowly rotating program of video art on board. You will not need to fasten your seat belts. What's especially sad about Tate's embrace of this luxury lifestyle Trojan Horse in their midst is that it seems to have superseded any other kind of interim exhibition this summer in the Turbine Hall, which now stands empty since Doris Salcedo's crack was filled in.

Serpentine Gallery Pavilion 2008. Designed by Frank Gehry © 2008 Gehry Partners LLP. Photo: John Offenbach / The roof. Photo: James Westcott

The king pavilion in London this summer, as every year, is at the Serpentine. Frank Gehry has designed an airy, open-sided and open-ended promenade with bleacher seats either side of a paved 'street', which is covered, kind of, by a jagged roof of intersecting glass planes that looks like it would leak in the rain (but we're not supposed to worry about such banalities – this is a pavilion after all).

Gehry and his practice, too accustomed to the perpetual 72 degrees of California, clearly have no clue how frickin' cold it can get on summer nights in London, let alone in October, when the pavilion's crowning event will take place during Frieze: a manifesto marathon – lasting deep into the cold autumn night – curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist, following on from his experiment and interview marathons (with Olafur Eliasson and Rem Koolhaas respectively) in previous years. Apart from an almost offensive insensitivity to climate, the pavilion totally fails to congeal any kind of collective atmosphere. No architectural attention seems to have been paid to the program of the pavilion, which Obrist has been developing with rampant enthusiasm in the past couple of years with the intention of making the pavilion not just a decorative or ponderous folly, but a content machine. The Serpentine pavilion is now first and foremost a venue, and a venue needs to be encompassing and embracing to be conducive to an event. Gehry's pavilion is more for strolling through on (if you're lucky) a sunny day in Kensington Gardens. This might be OK if the structure was truly, wonderfully frivolous or extravagant, but it's actually cumbersome (heavy wood disguising steel beams), has appalling attention to detail (are those handrails nabbed from a local swimming pool?), and is conservative at heart, doing nothing to push Gehry's practice into new realms, and looks alternately like a monkey house in a zoo, a sauna, or a piece of furniture from Ikea made without the instructions.

The criteria for the Serpentine's selection of architects is that they must never have built a structure in England. They've bagged some stellar names since the pavilion program started in 2000, including Zaha Hadid, Daniel Libeskind, Oscar Neimeyer, Rem Koolhaas and now Gehry himself. But there are numberless other architects who haven't built in the UK before. Maybe it's time for the Serpentine to drop its other condition: as well as never having built in the UK, the pavilion architect must also be a starchitect.

The Serpentine could take a leaf out of P.S.1's book. For their annual Young Architects Program, they hold a competition, inviting new, innovative practices to submit proposals for a structure in the courtyard (this year it's a functioning farm, by Work Architecture Company). The Serpentine could do with some of this ground-level innovation to relieve them of the pressure of having to come up with an expensive (or expensive-looking) masterpiece every year.

Architect Sou Fujimoto, artist Cao Fei and her translator and Storefront for Art and Architecture director Joseph Grima giving presentations at the Serpentine pavilion

Last week at the Serpentine, Cao Fei opened a small exhibition of her RMB City – a fantasy, composite Chinese city of the near future, built in Second Life, where you can construct anything you like, if you have the time and the skill. At a talk in the pavilion later that evening about the nature and role of pavilions, Ben Aranda, an architect with ArandaLasch who is building a pavilion with the artist Matthew Ritchie, made the illuminating remark that "Pavilions are the Second Life of architecture" – meaning they should be unencumbered, predictive, free to breathe new life into the more workaday aspects of the discipline. If only the immediate surroundings held out such promise.