Thursday, April 21. 2011

Via MIT Technology Review

-----

An experimental system would tighten the limits on information provided to websites.

By Erica Naone

|

| Credit: iStockphoto |

Today, many websites ask users to take a devil's deal: share personal information in exchange for receiving useful personalized services. New research from Microsoft, which will be presented at the IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy in May, suggests the development of a Web browser and associated protocols that could strengthen the user's hand in this exchange. Called RePriv, the system mines a user's behavior via a Web browser but controls how the resulting information is released to websites that want to offer personalized services, such as a shopping site that automatically knows users' interests.

"The browser knows more about the user's behavior than any individual site," says Ben Livshits, a researcher at Microsoft who was involved with the work. He and colleagues realized that the browser could therefore offer a better way to track user behavior, while it also protects the information that is collected, because users won't have to give away as much of their data to every site they visit.

The RePriv browser tracks a user's behavior to identify a list of his or her top interests, as well as the level of attention devoted to each. When the user visits a site that wants to offer personalization, a pop-up window will describe the type of information the site is asking for and give the user the option of allowing the exchange or not. Whatever the user decides, the site doesn't get specific information about what the user has been doing—instead, it sees the interest information RePriv has collected.

Livshits explains that a news site could use RePriv to personalize a user's view of the front page. The researchers built a demonstration based on the New York Times website. It reorders the home page to reflect the user's top interests, also taking into account data collected from social sites such as Digg that suggests which stories are most popular within different categories.

Livshits admits that RePriv still gives sites some data about users. But he maintains that the user remains aware and in control. He adds that cookies and other existing tracking techniques sites already collect far more user data than RePriv supplies.

The researchers also developed a way for third parties to extend RePriv's capabilities. They built a demonstration browser extension that tracks a user's interactions with Netflix to collect more detailed data about that person's movie preferences. The extension could be used by a site such as Fandango to personalize the movie information it presents—again, with user permission.

"There is a clear tension between privacy and personalized technologies, including recommendations and targeted ads," says Elie Bursztein, a researcher at the Stanford Security Laboratory, who is developing an extension for the Chrome Web browser that enables more private browsing. "Putting the user in control by moving personalization into the browser offers a new way forward," he says.

"In the medium term, RePriv could provide an attractive interface for service providers that will dissuade them from taking more abusive approaches to customization," says Ari Juels, chief scientist and director of RSA Laboratories, a corporate research center.

Juels says RePriv is generally well engineered and well thought out, but he worries that the tool goes against "the general migration of data and functionality to the cloud." Many services, such as Facebook, now store information in the cloud, and RePriv wouldn't be able to get at data there—an omission that could hobble the system, he points out.

Juels is also concerned that most people would be permissive about the information they allow RePriv to release, and he believes many sites would exploit this. And he points out that websites with a substantial competitive advantage in the huge consumer-preference databases they maintain would likely resist such technology. "RePriv levels the playing field," he says. "This may be good for privacy, but it will leave service providers hungry." Therefore, he thinks, big players will be reluctant to cooperate with a system like this.

Livshits argues that some companies could use these characteristics of RePriv to their advantage. He says the system could appeal to new services, which struggle to give users a personalized experience the first time they visit a site. And larger sites might welcome the opportunity to get user data from across a person's browsing experience, rather than only from when the user visits their site. Livshits believes they might be willing to use the system and protect user privacy in exchange.

Copyright Technology Review 2011.

Via Libération

-----

par Alexandre Hervaud

Capture Ecrans

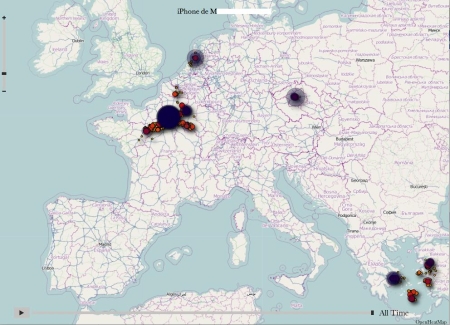

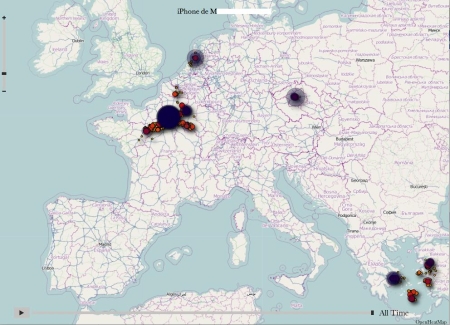

Dire où l’on se trouve en permanence via son smartphone, c’est simple comme bonjour : on peut le déclamer à qui ça intéresse (indice : personne) via les versions mobiles des réseaux sociaux type Facebook ou Twitter, ou check-iné comme un fou sur les appli spécifiques de géolocalisation comme Foursquare. Mais il y a un autre moyen, d’autant plus simple qu’il est automatique : avoir un iPhone et permettre sans le savoir à Apple de pister nos moindres déplacements.

La découverte est signée Alasdair Allan et Pete Warden, deux spécialistes qui l’ont annoncé aujourd’hui à la conférence Where 2.0 après l’avoir explicité sur le site Radar. Leur trouvaille peut être résumée ainsi : les iPhone et iPad 3G fonctionnant sous le système d’exploitation iOS4 (disponible depuis juin 2010) enregistrent régulièrement la localisation des produits dans un fichier caché, dont le contenu est restauré à chaque sauvegarde ou migration d’appareil.

Concrètement, d’après Radar, les localisations sont stockées dans un fichier appelé consolidated.db, avec coordonnées géographiques évoluant en fonction de la date d’enregistrement. La chose n’est pas toujours archi précise, triangularisation oblige, mais un test auprès des collègues de Liberation.fr montre le genre de données ainsi enregistrées :

Un logiciel baptisé iPhone Tracker est disponible pour lire à son tour ce genre de traces. En mouvement (soit en faisant évoluer la chronologie), ça donne ça :

Washington DC to New York from Alasdair Allan on Vimeo.

Radar précise qu’à ce stade, rien ne prouve que ces données puissent échapper au contrôle de l’utilisateur (comprendre : être envoyées via le Net à des serveurs cachés contrôlés par de maléfiques Big Brother en puissance suivant la moindre de nos traces). De même, l’existence même de ce type d’informations n’est pas en soi une nouvelle : les opérateurs téléphoniques en disposent et peuvent les transmettre aux autorités dans certaines circonstances (enquêtes, etc.), mais uniquement sur demande en bonne et due forme (mandat, par exemple). Le problème ici soulevé est que le fichier en question n’est pas du tout crypté, donc facilement accessible en cas de vol ou d’emprunt de téléphone, par exemple. Des fonctionnalités permises par l’iOS4, comme la classification automatiques des photos prises par l’iPhone en fonction du lieu de la prise de vue (cf capture à droite), peuvent éventuellement constituer une piste d’explication quant à la présence d’un tel fichier dans le téléphone.

Parmi les pistes suggérées par Radar pour éviter ce genre de désagrément, on peut citer l’option « Encrypt iPhone Backup » accessibles via les paramètres d’iTunes une fois l’appareil connecté à l’ordinateur. Alasdair Allan et Pete Warden expliquent en détail leur trouvaille dans la vidéo ci-dessous (en anglais, 20 minutes) :

Pour la petite histoire, Peter Warden a travaillé durant cinq ans pour Apple (mais jamais directement sur l’avancée de l’iPhone), avant de quitter l’entreprise « en bons termes » il y a trois ans. Sur la page permettant de télécharger iPhone Tracker, qu’ils ont conçus eux-même, les deux geeks semblent presque déçus de leur découverte : « on est tous les deux de grands fans des produits Apple, et on ne prend vraiment aucun plaisir à mettre en avant ce problème ».

Monday, April 04. 2011

Via OWNI

-----

by Marie D. Martel

Nous dirigeons-nous vers une technoculture du prêt, du partage, du streaming ?

Trop d’objets autour de nous, trop de bruit dans notre champ visuel, dans nos agrégateurs, dans nos résultats de recherche, trop de super-butinage (power-browsing), trop consommer, accumuler, remplir, excéder, évaluer, élaguer, se débarrasser, recycler-réduire-réutiliser, ouvrir la fenêtre, pas quinze fenêtres, respirer, relaxer, se vider l’esprit. C’est le printemps et une saison nouvelle qui s’annonce aux teintes discrètes (chromophobes ?) du néominimalisme.

After the bacchanal of post-modernism, the time has again come for neo-minimalism, neo-ascetism, neo-denial and sublime poverty. (Juhani Pallasmaa, cité dans Wikipedia)

ou encore :

By definition, « neo-minimalists » don’t have an overabundance of things in their lives. But one thing they tend to have more and more of these days is visibility. Recently, The New York Times talked to some people participating in the 100 Thing Challenge about how it has affected their lives; The BBC looked into the « Cult of Less; » and here on Boing Boing, Mark has beengetting down to the nitty-gritty of what the « lifestyle hack » involves. The common thread here is a growing number of people are realizing that our mountains of physical stuff are actually cluttering up more than just our houses. »

Cet extrait provient d’un article publié sur Boing Boing (traduit dans Le Courrier International), dans lequel Sean Bonner explore la dématérialisation ou la décroissance matérielle comme une possibilité issue des technologies actuelles et qui nous permet de reconsidérer nos interactions avec le monde et les autres en favorisant l’expérience plutôt que la consommation. À Toronto, le même auteur a aussi animé une présentation [en] sur le courant des technomades.

L’usage de circonstance par le prêt, le partage, le streaming

D’autres journalistes, comme Ramon Munez d’El Païs ont, dans la même perspective, élaboré l’idée que la propriété est un fardeau et que l’avenir de la consommation de la culture n’est plus lié à la propriété mais à l’usage de circonstance par le prêt, le partage, le streaming :

Après avoir été pendant trois siècles la valeur suprême de la civilisation occidentale, la propriété cesse d’être à la mode. Ne vous y trompez pas : il ne s’agit pas d’un retour du communisme ou d’une vague de ferveur qui nous ramènerait au détachement matériel des premières communautés chrétiennes. Ce sont le capitalisme lui-même, son incitation permanente à consommer et les technologies liées à Internet qui viennent bousculer des habitudes que l’on croyait bien enracinées. À quoi bon posséder des biens, les stocker, les entretenir, les protéger des voleurs, lorsqu’on dispose d’une offre illimitée de produits et de services accessibles en quelques clics ou moyennant la signature d’un contrat de location ?

Si cette tendance ne se limite pas au numérique, c’est sur Internet que la révolution est le plus avancée. Le téléchargement de contenus cède du terrain au streaming [diffusion en continu], c’est-à-dire à la reproduction instantanée de musique et de vidéos sans qu’il soit besoin de les conserver sur le disque dur de l’ordinateur. Des milliers de sites, légaux et illégaux, proposent un catalogue illimité de logiciels, films, morceaux de musique et jeux vidéo. Le succès du site de musique suédois Spotify ou du portail espagnol de séries télévisées Seriesyonkis vient bousculer les habitudes des consommateurs.

YouTube, le célèbre portail de vidéos en ligne de Google, est le symbole de la révolution en marche. Ses chiffres laissent pantois. Sur toutes les vidéos regardées chaque mois aux États-Unis, 43% (14,63 milliards) sont diffusées par YouTube, selon la société d’études de marché comScore. YouTube est suivi de près par Hulu, un site de streaming qui propose gratuitement des films et des séries télévisées. Avec 1,2 milliard de vidéos regardées, Hulu dépasse non seulement des monstres d’Internet comme Yahoo! ou Microsoft, mais aussi les portails de chaînes et de studios comme Viacom, CBS ou Fox.

D’après une étude sur le paysage audiovisuel espagnol réalisée en 2010 pour le compte de l’opérateur Telefónica et de la chaîne de télévision privée Antena, 3, 30% des internautes espagnols déclarent télécharger moins de fichiers, tandis que la moitié d’entre eux assurent que le streaming est leur manière habituelle de consommer des contenus audiovisuels sur Internet. “On constate un essor du streaming depuis au moins le printemps 2009”, assure Felipe Romero, l’un des auteurs de l’étude. “À court terme, les deux méthodes – téléchargement et streaming – vont coexister, mais il est clair que la seconde va prendre de plus en plus d’ampleur.”

Sur le blog Agnostic, May Be, on mentionne également cet article qui témoigne de l’émergence de la culture du partage dans le Time [en] :

[T]he ownership society was rotting from the inside out. Its demise began with Napster. The digitalization of music and the ability to share it made owning CDs superfluous. Then Napsterization spread to nearly all other media, and by 2008 the financial architecture that had been built to support all that ownership — the subprime mortgages and the credit-default swaps — had collapsed on top of us. Ownership hadn’t made the U.S. vital; it had just about ruined the country.

L’étape suivante franchie par le blogueur Andy Woodworth [en] (incidemment élu dans le palmarès 2010 des Shakers and Movers [en]) m’intéresse tout particulièrement. Il fait l’hypothèse qu’en ce moment l’attrait pour les bibliothèques reposerait peut-être moins sur la récession économique que sur l’accroissement du nombre de gens qui préfèrent emprunter plutôt que posséder.

L’émergence de cette culture suggère des possibilités et des tendances sur lesquelles les bibliothèques pourraient largement capitaliser, dit-il. Comment ? Pas seulement en incarnant elles-mêmes les instances équipées pour prêter des documents à partir de leurs collections mais peut-être surtout en se positionnant comme des facilitateurs, ou des médiateurs, capables de négocier et de supporter les citoyens en vue d’accéder aux ressources disponibles dans la déferlante du web.

Mais la question la plus évidente est la suivante : est-ce que les bibliothèques seront en mesure de profiter de l’apparition de cette société du prêt et du partage ? Elles apparaissent elles-mêmes souvent éreintées par les résistances, trop déboussolées pour servir de guide à qui ce soit, sans vision, sans plan pour penser la culture numérique au-delà de cet effort qui les amène à prononcer et à servir à toutes les sauces, le mot magique de la « bibliothèque numérique ».

Wednesday, August 25. 2010

-----

The way privacy is encoded into software doesn't match the way we handle it in real life.

By Danah Boyd

|

| Credit: Nick Reddyhoff |

Each time Facebook's privacy settings change or a technology makes personal information available to new audiences, people scream foul. Each time, their cries seem to fall on deaf ears.

The reason for this disconnect is that in a computational world, privacy is often implemented through access control. Yet privacy is not simply about controlling access. It's about understanding a social context, having a sense of how our information is passed around by others, and sharing accordingly. As social media mature, we must rethink how we encode privacy into our systems.

Privacy is not in opposition to speaking in public. We speak privately in public all the time. Sitting in a restaurant, we have intimate conversations knowing that the waitress may overhear. We count on what Erving Goffman called "civil inattention": people will politely ignore us, and even if they listen they won't join in, because doing so violates social norms. Of course, if a close friend sits at the neighboring table, everything changes. Whether an environment is public or not is beside the point. It's the situation that matters.

Whenever we speak in face-to-face settings, we modify our communication on the basis of cues like who's present and how far our voices carry. We negotiate privacy explicitly--"Please don't tell anyone"--or through tacit understanding. Sometimes, this fails. A friend might gossip behind our back or fail to understand what we thought was implied. Such incidents make us question our interpretation of the situation or the trustworthiness of the friend.

All this also applies online, but with additional complications. Digital walls do almost have ears; they listen, record, and share our messages. Before we can communicate appropriately in a social environment like Facebook or Twitter, we must develop a sense for how and what people share.

When the privacy options available to us change, we are more likely to question the system than to alter our own behavior. But such changes strain our relationships and undermine our ability to navigate broad social norms. People who can be whoever they want, wherever they want, are a privileged minority.

As social media become more embedded in everyday society, the mismatch between the rule-based privacy that software offers and the subtler, intuitive ways that humans understand the concept will increasingly cause cultural collisions and social slips. But people will not abandon social media, nor will privacy disappear. They will simply work harder to carve out a space for privacy as they understand it and to maintain control, whether by using pseudonyms or speaking in code.

Instead of forcing users to do that, why not make our social software support the way we naturally handle privacy? There is much to be said for allowing the sunlight of diversity to shine. But too much sunlight scorches the earth. Let's create a forest, not a desert.

Danah Boyd is a social-media researcher at Microsoft Research New England, a fellow at Harvard University's Berkman Center for Internet and Society, and a member of the 2010 TR35.

Copyright Technology Review 2010.

Personal comment:

In connection to this post, you can look a this picture from Mashable site.

Tuesday, June 22. 2010

Via Mashable

-----

Apple’s new privacy policy contains a small new paragraph of big importance: it gives the company license to store “the real-time geographic location of your Apple computer or device” and share it with “partners and licensees.” As if we haven’t had enough privacy kerfuffles of late. Apple’s new privacy policy contains a small new paragraph of big importance: it gives the company license to store “the real-time geographic location of your Apple computer or device” and share it with “partners and licensees.” As if we haven’t had enough privacy kerfuffles of late.

Apple goes on to assure customers in the remainder of the new clause that location data is “collected anonymously in a form that does not personally identify you.” Still, there seems to be no effective method of opting out of the data storage and sharing, as you’ll need to agree to the new terms and conditions before downloading new apps or any media from the iTunes store.

The company gives a nod to MobileMe’s “Find My iPhone” feature as one of the services that requires personal location information to work, but it’s not saying much about other details, including who the data will be shared with and for how long it will be stored. Apple says the information it collects will be used to “provide and improve location-based products and services”; check out the full text of the new paragraph in the privacy policy below:

“To provide location-based services on Apple products, Apple and our partners and licensees may collect, use, and share precise location data, including the real-time geographic location of your Apple computer or device. This location data is collected anonymously in a form that does not personally identify you and is used by Apple and our partners and licensees to provide and improve location-based products and services. For example, we may share geographic location with application providers when you opt in to their location services.

Some location-based services offered by Apple, such as the MobileMe “Find My iPhone” feature, require your personal information for the feature to work.”

What do you think: should iPhone, iPad and Mac users be wary of this change in the privacy policy? Will this be business as usual now that geographic data is easy to come by on most of our devices?

[via LA Times]

Personal comment:

Is Apple the new evil? Spread the message...

Tuesday, May 18. 2010

-----

Making more user information public has both privacy and security dangers, experts warn.

By Robert Lemos

Last month, Facebook finally crossed a line. The company announced that it would make certain user information--including a user's name, hometown, education, work, and "likes" and "dislikes"--permanently public.

Facebook's default privacy policy has gradually shifted to expose more user data to the wider Web, but the reaction to this latest change has been significant. Last week, a collection of European data-protection authorities known as the Article 29 Working Group sent Facebook a letter chastising the company for not allowing users to limit access to their social data. The letter follows a similar criticism of Facebook by several members of congress, such as Sen. Charles Schumer, D-NY, over the past month. The reaction from privacy advocacy groups, and from many of Facebook's users, has also been vocal.

Some experts also say that the increase in information disclosure could have a serious side-effect--opening up new opportunities for hackers. Kevin Johnson, a senior researcher with security firm InGuardians, uses Facebook as a starting point for his job: testing companies' network security. Many times, he says, the most significant vulnerabilities are not in hardware or software, but in a users' use of social networks. The information leaked on social networking sites can be used to impersonate a legitimate person, in order to recover a password, for example; or to trick users into opening a malicious file by making it appear to come from a friend or a colleague.

"As a penetration tester--as an attacker--Facebook's privacy settings have made my job easier," Johnson says. "In the past, before two years ago, we had to trick people into running a [rogue] application [to collect data]. Now, the majority of people out there--the bulk of Facebook--run under default privacy settings."

Pushed by a need to monetize the data entered by users, Facebook has increasingly loosened its privacy policies. In 2005, the company's original policy stated that no information would be shared with people "who [do] not belong to at least one of the groups specified by you in your privacy settings." By 2010, the policy had changed to one that focuses on sharing much more information, stating that applications and Web sites "will have access to General Information about you." The text of the company's privacy policy has grown nearly 500 percent and users are now required to navigate some 50 different privacy settings.

"Facebook says that they are introducing more privacy settings because they want to give users more control, but what they have done is make things more confusing," says Fred Stutzman, a privacy researcher and PhD candidate at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. "Over time they have made changes that make people's information more open, because that is how they drive the use of the network."

"This is something that is different from how Facebook had been operating," says Kurt Opsahl, a senior staff attorney with the Electronic Frontier Foundation. "In the past, they encouraged sharing that information, but now they have taken information that many people consider private and made it public, and they did so in a very heavy-handed way."

Yet, as Facebook has grown, users have become savvier about their data security, Stutzman says. Students at UNC Chapel Hill, for example, have increasingly opted to set their Facebook privacy to the highest possible setting, with almost 60 percent of students using the "Friends Only" setting in 2008 compared with less than 20 percent in 2005. Stutzman says that people have to overcome their preference to run under the default settings and opt not to change them.

Alessandro Acquisti, associate professor of information science and policy at Carnegie Mellon University, argues that Facebook is likely counting on that psychology to limit the number of people who ratchet up the privacy settings. "What is happening, it is almost a bait and switch technique," he says. "Every time they change the status quo, they are getting people more and more adjusted to the habit of disclosing information. If you told people five years ago that all these different fields are public, they would say, 'No way.' "

Facebook says that some information--a person's name, her network of connections, and pages that she likes and dislike have always been public. The user's photo, gender, and current city have all been added to the must-be-public profile information, the company acknowledges, but it says that only a small fraction of users are changing their settings to restrict access to information.

"The overwhelming majority of users have made all of this information available to everyone," a spokesman says. "We've found that the small percentage who have restricted any of this information have intended to prevent contact from nonfriends."

However, Facebook may not find an easy way out of the current controversy. In February 2009, when users were upset about other changes to its terms of service, the company created its Facebook Principles, a list of promises of how the company would treat its users and their data, including that "people should own their information, they should have the freedom to share it with anyone they want and take it with them anywhere they want, including removing it from the Facebook Service."

The company has failed to live up to those principles, says the EFF's Opsahl. "It is not just a matter of, can Facebook weather the storm of criticism and keep their users--they have a real situation here," Opsahl says. "But they have an opportunity as well. They can try and fix this problem and regain their users' trust."

Copyright Technology Review 2010.

Personal comment:

In connection with the post below... A question that rises now every month or two months and that is turning into a fight between "privacy" vs "publicy" advocates. I'm on the side of "open publicy" and "proprietary privacy", certainly not on the side of changing rules every two weeks for profit reasons...

Monday, May 17. 2010

-----

by Jolie O'Dell

Free software pioneer Richard Stallman spoke with us recently about the principles of free and open source programs, and what he had to say is as relevant and revolutionary as when he first started working in this field 30 years ago. Free software pioneer Richard Stallman spoke with us recently about the principles of free and open source programs, and what he had to say is as relevant and revolutionary as when he first started working in this field 30 years ago.

Our community has been talking a lot lately about what it means to be open, about what makes software open, about what makes companies open. No matter what talk of “openness” you hear in the media, no major web company — not Facebook, not Google, not Adobe and certainly not Apple — is creating truly free and open applications. Some may make gestures toward this ideology with APIs or “open source” projects, but ultimately, the company controls the software and the users’ data.

At the end of the day, if you want freedom and privacy, the only way to attain those goals is to abstain from proprietary software, including media players, social networks, operating systems, document storage, email services and any other program that is licensed, patented and locked down by a corporation. If you prefer convenience — well, best to stop complaining about your loss of freedom and/or privacy.

Like many heroes of the digital era, Richard Stallman is largely unsung by the general populace. Yet when it comes to user privacy and technological freedom, he’s probably one of the most committed individuals in the world.

By freedom, he means four things:

- The software should be freely accessible.

- The software should be free to modify.

- The software should be free to share with others.

- The software should be free to change and redistribute copies of the changed software.

Stallman started the Free Software Foundation. He even worked to make an operating system (GNU/Linux) that could be entirely free. And he is deeply opposed to proprietary software, software with commercial licenses that fly in the face of everything he calls freedom.

If you’ve ever downloaded music illegally, if you’ve ever complained about closed platforms, if you’ve ever gotten a serial number online for software you didn’t buy, if you’re worried about social networks controlling your data, you need to hear what Stallman has to say.

We got the chance to interview Stallman extensively at WordCamp San Francisco, and we’ll be posting segments of that interview each week. Stay tuned for insights on music sharing, Apple versus Adobe and more.

Note: Stallman asked that we use Ogg Theora, an open format, for encoding this video. To download the original video, go to its Wikimedia page. This video is published under a Creative Commons-No Derivatives license.

Personal comment:

There's a debate now on Mashable about what is open vs what is proprietary in technology. Especially now that this has become a marketing term full of lies.

Interesting debate to follow, in particular for us in the perspective of two projects we are currently working on where we'll claim for an open approach regarding technology in public spaces (all of them, including in outer space! I-Weather as Deep Space Public Lighting) or where we'll adopt a critical approach regarding surveillance (technologies) in the public space (a future "Paranoid Shelter" project we are working on for a while), followed maybe a bit later by a collaboration ("Globale Paranoïa") with French writer and essayist Eric Sadin.

It's a really a whole big debate, quite complex, just as the question of freedom that is a complex one. For our part, we are interested maybe in a less complex question at first. The one of public space (public is not free so to say, it is shared in different ways and allows for, or offer this and that but not everything).

Tuesday, February 23. 2010

A new app makes it possible to identify people and learn about them just by pointing your phone.

By Erika Jonietz

|

Enhanced image: A prototype app for smart phones matches live images of people to stored profiles and shows icons for social networking sites around their heads.

Credit: The Astonishing Tribe |

An application that lets users point a smart phone at a stranger and immediately learn about them premiered last Tuesday at the Mobile World Congress in Barcelona, Spain. Developed by The Astonishing Tribe (TAT), a Swedish mobile software and design firm, the prototype software combines computer vision, cloud computing, facial recognition, social networking, and augmented reality.

"It's taking social networking to the next level," says Dan Gärdenfors, head of user experience research at TAT. "We thought the idea of bridging the way people used to meet, in the real world, and the new Internet-based ways of congregating would be really interesting."

TAT built the augmented ID demo, called Recognizr, to work on a phone that has a five-megapixel camera and runs the Android operating system. A user opens the application and points the phone's camera at someone nearby. Software created by Swedish computer-vision firm Polar Rose then detects the subject's face and creates a unique signature by combining measurements of facial features and building a 3-D model. This signature is sent to a server where it's compared to others stored in a database. Providing the subject has opted in to the service and uploaded a photo and profile of themselves, the server then sends back that person's name along with links to her profile on several social networking sites, including Twitter or Facebook. The Polar Rose software also tracks the position of the subject's head--TAT uses this information to display the subject's name and icons for the Web links on the phone's screen without obscuring her face.

"It's a very robust approach" to facial recognition, says Andrew Till, vice president of marketing solutions at Teleca, a mobile software consulting company in the United Kingdom. "It's much, much better than what I've previously seen."

Till says that applying image and face recognition to the trend of posting photos on social networking sites opens up interesting new possibilities. "You start to move into very creative ways of pulling together lots of services in a very beneficial way for personal uses, business uses, and you start to get into things that you otherwise wouldn't be able to do," he says.

Polar Rose's algorithms can run on the iPhone and on newer Android phones, says the company's chief technical officer and founder, Jan Erik Solem. The augmented ID application uses a cloud server to do the facial recognition primarily because many subjects will be unknown to the user (so there won't be a matching photo on the phone), but also to speed up the process on devices with less processing power.

Academic and company research groups have developed augmented reality applications, which superimpose virtual objects and information on top of the real world, for more than a decade. But until the past year or so, all of these prototype applications required bulky headsets and laptop computers. With more powerful sensors, cameras, and microprocessors built into mobile phones, however, augmented reality applications have begun hitting the mainstream. Several apps take advantage of the GPS chips and compasses available in newer smart phones. For example, PresseLite's Metro Paris app and Acrossair's Nearest Tube provide iPhone users with directions to nearby subway stops.

But Gärdenfors calls such applications "relatively crude." They often obscure objects with labels, he notes, and are sometimes limited by the fact that location information may not be available. He thinks that many augmented reality services could benefit from including elements of computer vision to make information retrieval and label positioning more precise. "This could absolutely work for other kinds of objects, and I think we'll see that soon," he says.

However, Gärdenfors notes that using computer vision to identify buildings and other objects holds challenges that they didn't encounter in developing the augmented ID application. "With facial recognition, it's so obvious what you want to search for," says Gärdenfors. "With other objects, it may be harder to tell which item on the screen you want to identify."

Gärdenfors says that TAT has taken potential privacy concerns with the technology seriously from the beginning. "Facial recognition can be a kind of scary thing, and you could use it for a lot of different purposes." For that reason, the company designed Recognizr as a strictly opt-in service: people would have to upload a photo and profile of themselves, and associate that with different social networks before anyone could use the service to identify them. "You should only be able to look at people who have signed up for this," Gärdenfors says.

A concept video of the augmented ID application that TAT posted on YouTube last summer garnered a great deal of attention. Gärdenfors says the company often uses this strategy to determine which ideas justify further development. A live demonstration also received a lot of interest at the Mobile World Congress. "We're probably going to partner with some company over the next couple of months to take it to the next level and actually build [a product]," Gärdenfors says. While this will require partnerships with a device maker, a mobile service provider, and social networking services, the technology is developed enough that a commercial application could be ready in as little as a month or two, he says.

Copyright Technology Review 2010.

----

Via MIT Technology Review

Personal comment:

Is it good or bad news (I remember that the "recognizer" were very evil creatures in the movie Tron ;))? You still need to be part of the system and accept it (apparently) to be recognized, which is good. But if it's as hard as systems like Facebook to sign out, then you might have lost your "right to disappear" for a very long time...

It's again this question of privacy vs. "publicy". Some people prefer to live in "private mode" by default (this was the old "de facto" way of living), while others prefer the contrary.

Friday, January 22. 2010

Facebook’s new approach to privacy is bold, pushing users to be increasingly public with their data.

This public sharing is the new “social norm”, said founder Mark Zuckerberg in a recent interview. But is Facebook really responding to cultural changes or simply encouraging the type of behavior that will help the company to grow fastest? Possibly both.

That’s the topic of my guest column today in the UK’s Telegraph newspaper.

-----

Via Mashable

Tuesday, January 12. 2010

Facebook veut imposer sa propre vision de la vie privée sur Internet

En proposant à ses membres de nouveaux paramètres de protection des données personnelles, parfois jugés trop laxistes, le fondateur de Facebook estime qu’il ne fait que suivre la nouvelle norme sociale.

Facebook joue à la girouette concernant la protection de la vie privée de ses membres. Début décembre, le site communautaire avait proposé à ses 350 millions utilisateurs une palette d’outils permettant de régler les paramètres de son profil et de mieux protéger ses données personnelles.

Mark Zuckerberg, fondateur et P-DG de Facebook, a expliqué, lors d’une interview vidéo accordée à Mike Arrington, du site TechCrunch.com, que le fait de partager des données privées sur Internet étaient désormais la “norme“.

“Les gens sont maintenant à l’aise avec l’idée de partager plus d’informations différentes, ils sont aussi plus ouverts et à plus d’internautes […] La norme sociale a évolué depuis quelques temps”, a-t-il estimé au micro de TechCrunch.

On peut ainsi comprendre que les membres de Facebook, et les internautes en général, ne seraient plus réticents à l’idée de partager leurs données personnelles, sur le réseau social comme sur la Toile…

Mark Zuckerberg tente ainsi, plus ou moins habilement, de justifier sa récente politique d’évolution des règles de sécurisation de la vie privée initiée par Facebook il y quelques semaines.

Facebook ne ferait que suivre la nouvelle norme sociale

Le réseau social propose ainsi à ses membres toute une série de filtres permettant de définir, au cas par cas, des règles d’accès pour chaque élément de son profil. Facebook laisse alors le choix aux internautes de conserver leurs paramètres initiaux ou alors de les faire évoluer suivant les nouvelles règles prônées.

Si l’internaute décide d’adopter ces nouvelles règles de confidentialité des informations qu’il diffuse sur le site, il peut alors restreindre ou, au contraire, ouvrir plus largement l’accès à différents éléments de leur profil (photos, vidéos) à ses contacts selon ses envies.

Mais nouveau système de paramètrage soulève la controverse. L’Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), une organisation non gouvernementale internationale dont le but est de défendre la liberté d’expression sur Internet, pointe du doigt le système de paramétrage par défaut, qui, de lui-même, propose un degré de confidentialité trop faible, en laissant trop d’informations personnelles librement accessibles.

De leur côté, des organisations comme l’Electronic Privacy Information Center ou le Center for Digital Democracy (CDD) ont déposé une plainte contre Facebook devant la Federal Trade Commission (FTC) pour contraindre Facebook à modifier les règles de confidentialité récemment établies.

Elles soupçonnent ainsi le réseau social d’avoir mis en place ce nouveau système pour que les internautes exposent plus d’informations personnelles en ligne.

Les données personnelles des utilisateurs peuvent rapporter gros à Facebook

Reste que Mark Zuckerberg pense que Facebook a su s’adapter au changement de mœurs, porté par ses jeunes utilisateurs. “Les enfants se sont toujours préoccupés du respect de leur vie privée, c’est juste que, pour ces jeunes, la notion de “vie privée” est très différente de ce qu’elle est pour les adultes”, a-t-il expliqué à Mike Arrington.

Fort de ses 350 millions de membres, Facebook a aujourd’hui mis le cap sur la rentabilité. Ainsi, la mise en place de ces paramètres par défaut sur Facebook devrait permettre aux robots des moteurs de recherche de repérer davantage d’informations laissées publiques par leurs auteurs, favorisant leur indexation en temps réel par Google ou Bing.com (Microsoft), avec lesquels Facebook vient de conclure des partenariats commerciaux…

Via ITespresso.fr par Anne Confolant

|

Apple’s new privacy policy contains a small new paragraph of big importance: it gives the company license to store “the real-time geographic location of your Apple computer or device” and share it with “partners and licensees.” As if we haven’t had

Apple’s new privacy policy contains a small new paragraph of big importance: it gives the company license to store “the real-time geographic location of your Apple computer or device” and share it with “partners and licensees.” As if we haven’t had  Free software pioneer Richard Stallman spoke with us recently about the principles of free and open source programs, and what he had to say is as relevant and revolutionary as when he first started working in this field 30 years ago.

Free software pioneer Richard Stallman spoke with us recently about the principles of free and open source programs, and what he had to say is as relevant and revolutionary as when he first started working in this field 30 years ago.