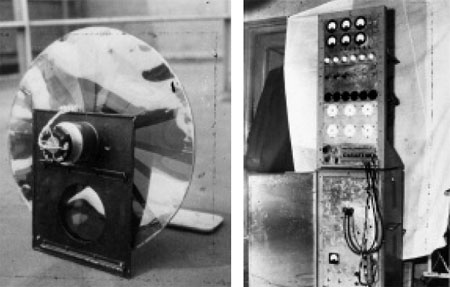

Grey Walter’s robotic tortoises ELSIE

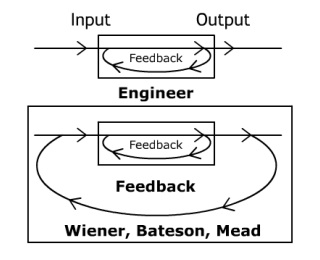

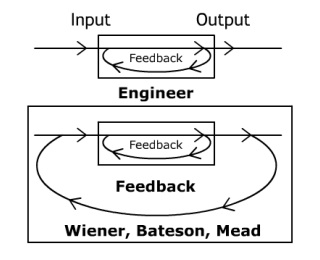

Usman Haque has, on several occasions, made the observation that there is an important difference between interactivity and responsiveness (see for example -pdf). A responsive system is a fundamentally linear set of relations, a kind of reaction where the same thing happens every time a given action is performed. A normal light switch is responsive in this sense. A typical light switch doesn’t consider any other variables, or have any other behavioural options. Pressing the switch will either turn it off or on, in what is a linear causal relationship. A properly interactive system is very different in its logical structure, and is characterised instead by a relational and circular (or more complex network) causality. In a properly interactive system, a given action will produce different results, because it depends upon the context at that moment, the history of previous interactions, and the relational creativity of the system. To take the banal example of a light switch again: in an interactive system an input might turn on a light, but it could equally result in other behaviour. A properly interactive light might set itself at different levels according to other sensor inputs, or the light might not come on at all, and instead curtains or windows might be opened to allow in more light. It might even ask you if you are afraid of the dark, or if you need help. It might try to sell you a torch, or it might just remind you that you are wearing shades. The post-war maverick ecologist and cybernetician Gregory Bateson used a different example to illustrate the same point. If you kick a stone, he said, then the trajectory of the stone is a simple mechanical affair, that can easily be calculated using Newton’s equations. If you kick a dog, then you do not know what is going to happen. It might bite you, or bark at you, or run away. A dog interacts with us. It has its own agency, and that is the important issue here.

One point to be made here then, is that many of the installations, systems and apps that we might broadly classify as interactive, are actually just responsive or reactive. There is nothing per se wrong with reactivity, and of course such responsive and reactive systems can in any case be ‘looped’ and networked to form components of more complex and properly interactive feedback systems. The important point rather, is that properly interactive systems are interesting, as they are able to stage a series of philosophical questions regarding the nature of agency and creativity – important questions that perhaps cannot be posed in any other way.

The way that circular causal systems which feature feedback and recursion act as minds was the broad research focus of the post war project of cybernetics, and has been the subject of a recently published book by Andrew Pickering, called The Cybernetic Brain – Sketches of Another Future (University of Chicago Press, 2010). In this work, Pickering takes the reader through this fascinating period of experimental work at the boundary of art and science, which he describes as “some of the most striking and visionary work that I have come across in the history of science and engineering”.

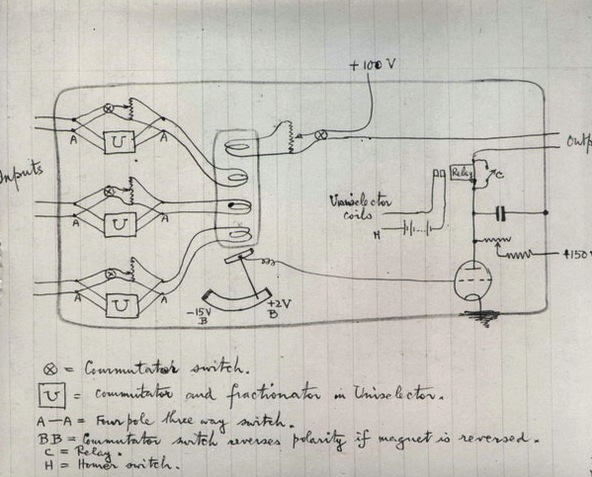

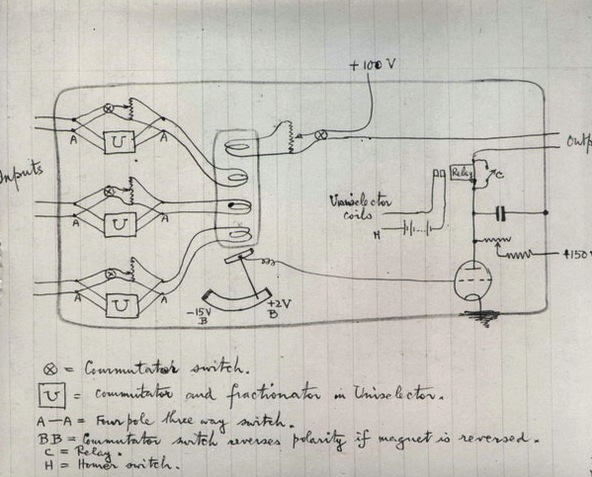

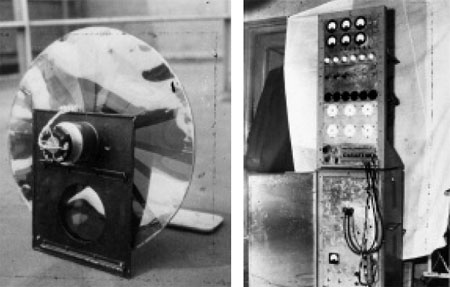

Pickering focuses upon the most radical traditions within cybernetic research, which largely arose out of the work of a series of distinctly eccentric British researchers, who he describes – borrowing a phrase from philosophers Giles Deleuze and Felix Guattari – as performing a nomadic science. He notes that “unlike more familiar sciences such as physics, which remain tied to specific academic departments and scholarly modes of transmission, cybernetics is better seen as a form of life, a way of going on in the world…” Pickering considers many experiments that have come to take on a legendary status within the history of cybernetics, ranging from Ross Ashby’s Homeostat (a network of four machines composed of movable magnets with electric connections through water, which would exhibit a range of emergent self-organised behaviours), Grey Walter’s robotic tortoises ELSIE and ELMER (which would respond to each other’s lights, or themselves in a mirror), to Stafford Beer’s remarkable Cybersyn project for Salvadore Allende’s government in Chile (an early form of the internet, which created the basis of a de-centralised socialist planned economy. For an information rich – though political analysis very poor – documentary, see here). Of particular interest to Pickering is the work of Gordon Pask, whose experimental installations and assemblages of various kinds captured in a uniquely distinct way, what Pickering describes as the “hylozoic wonder” of radical cybernetics – that is to say, under what conditions can we think of all matter as (at least capable of) being alive and thinking.

Gordon Pask was heavily influenced by the ideas of Gregory Bateson – in particular Bateson’s anthropological work with various Balinese tribes, and later with family therapy and schizophrenia. In this research Bateson showed how our very experience of being a ‘self’ is produced out, or emerges out of, our participation in a network or ecology of conversations with other actors in our environment: people, objects, rituals and so on. Bateson suggested that

“the total self-corrective unit which processes information, or as I say, ‘thinks’, ‘acts’ and ‘decides’, is a system whose boundaries do not at all coincide with the boundaries either of the body or of what is popularly called the ‘self’ or ‘consciousness’.”

For Pask famously, the conversation became the paradigm for thinking about interactivity – much of which focused on the question of how do systems learn and teach, or as Bateson described it, what is deuterolearning: learning how to learn? Pask’s writings in this area can often be rather obscure, especially to the newcomers to the field, and Pickering provides an excellent introduction to these projects – including Musicolour, SAKI, Eucrates, CASTE, and the yet more experimental chemical computing projects – many of which were developed in association with architecture schools and in art settings. In all of these projects, Pickering reminds us, Pask is ultimately staging questions about who we are, and what we and our world might be; questions which the ‘ecology of mind’ of radical cybernetics can still help us with today. In this regard, I can’t put it any better than Usman Haque, who has stated that:

“It is not about designing aesthetic representations of environmental data, or improving online efficiency or making urban structures more spectacular. Nor is it about making another piece of high-tech lobby art that responds to flows of people moving through the space, which is just as representational, metaphor-encumbered and unchallenging as a polite watercolour landscape. It is about designing tools that people themselves may use to construct – in the widest sense of the word – their environments and as a result build their own sense of agency. It is about developing ways in which people themselves can become more engaged with, and ultimately responsible for, the spaces they inhabit.”

–

About the Author: Jon Goodbun is researcher interested in networks of architecture, process philosophy, radical cybernetics, urban political ecology, and the natural and cognitive sciences. He sometimes refer to himself as an metropolitan tektologist, for want of a better description. His work focuses on near and medium term future scenarios. He is currently printing his PhD, working on a book ‘Critical and Maverick Systems Thinkers’, and planning some kind of exhibition on ‘Ecological Aesthetics, Empathy and Extended Mind’.

http://www.rheomode.org.uk