The property market is in the doldrums, mortgages are elusive but there is still some hope for the first-time buyer: the paper house.

Wednesday, January 28. 2009

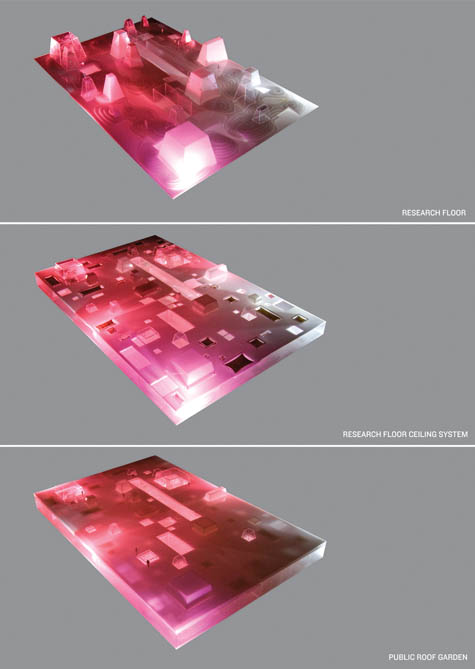

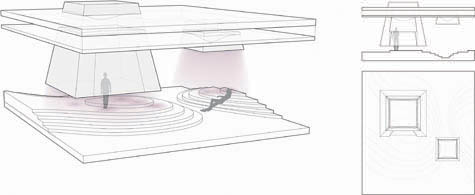

Cardiopulmonary Spatialization

[Image: From "Change of Heart: Rethinking the Prescriptive Medical Environment" by Marina Nicollier].

[Image: From "Change of Heart: Rethinking the Prescriptive Medical Environment" by Marina Nicollier].

The idea that architecture might have medical effects on the people who experience it was the premise of a project by Marina Nicollier produced this year at Rice University.

In the project's accompanying documentation, Nicollier writes that we must learn "to create spaces that provide, through their experience and material substance, enough variability in environmental effects that individual differences in reception and response can be studied and used as a part of curative regimes."

In other words, the sensorial experience of architecture could play a role in healing – or, as Nicollier explains, "spaces themselves should act as experiential platforms that provide a broader spectrum of environmental qualities, so that we may better understand their effects on our psychology – and ultimately, on our physiology."

[Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier].

[Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier].

From the project description:

- The human body responds to its spatial and environmental surroundings in very subtle ways. Our most basic reactions to our environment can be read, essentially, in our vital signs; yet as many of these phenomena are subtle enough to be easily overlooked without some sort of monitoring device, they have been too often dismissed as fleeting emotional and sensorial effects that have little impact on our physiological system as a whole. These qualities can do much more. They can act as an architectural base for a very important body of research, expanding beyond the limited range of possibilities imposed on them by existing models of medical environments.

To perform a test-run for these propositions, Nicollier has designed a "cardiology research facility adjacent to two major medical institutions in Mexico City."

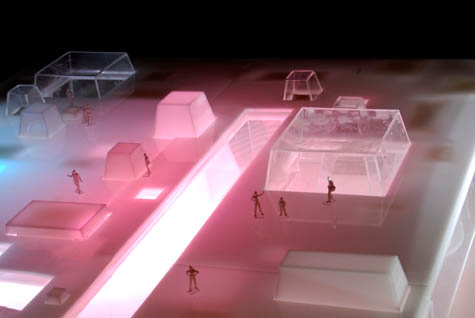

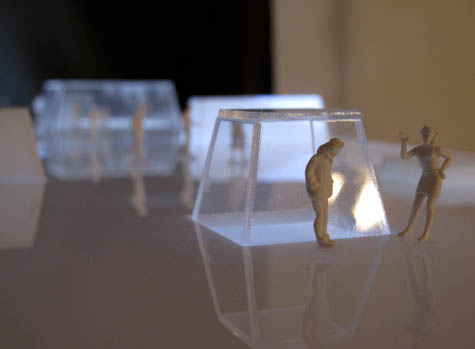

You would wander through the building, hooked up to electrocardiographs, every flutter of heart valve and sweat gland monitored by doctors from afar.

[Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier].

[Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier].

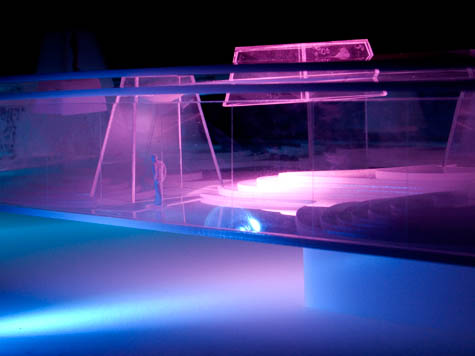

I was on Nicollier's final thesis review the other week, where I joked that the project was like a visual combination of Barbarella and Constant's New Babylon, by way of A Clockwork Orange – an immensely positive combination, I might add.

But that same impression strikes me today: that this is the kind of project Constant might have designed had he been more interested in the avant-garde spatial application of cardiac self-analysis.

It is the megastructure as medical cocoon, architecture designed to stimulate the human nervous system.

[Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier; think of it as a Foucauldian application of Winston Churchill's famous phrase, that "We shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us." Only here, those buildings cause heart palpitations].

[Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier; think of it as a Foucauldian application of Winston Churchill's famous phrase, that "We shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us." Only here, those buildings cause heart palpitations].

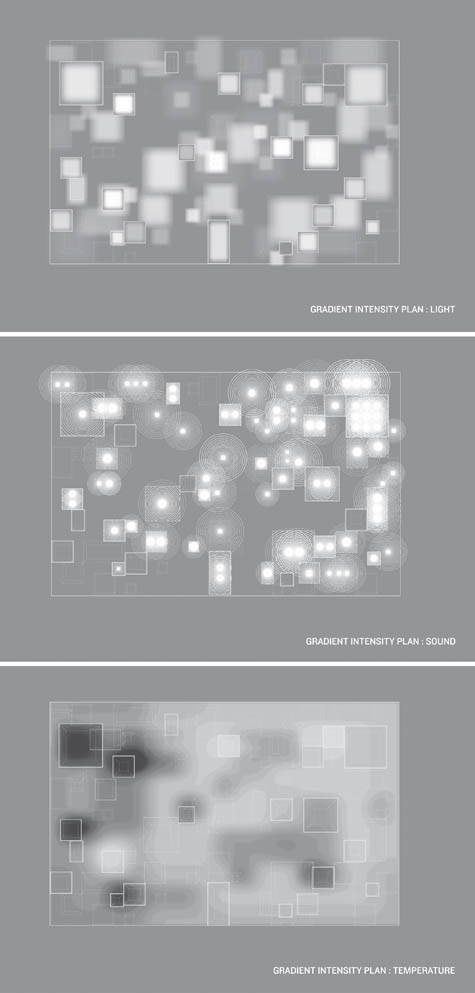

Nicollier's cardiology research lab "relies on an experience-based design generated on a series of gradient intensities," she writes.

She then contrasts this brilliantly with the design of modernist sanitariums, highlighting what might be called the medical origin of modern architecture:

- Popular ideas about what constitutes a healthy environment gave rise to many of the components that became the formal trademarks of modernism – the flat roof was devised as a means to provide additional sunning surfaces for tubercular patients; while the deep verandas, wide private balconies, and covered corridors served as organizational tools to isolate contagious patients from the general staff.

Indeed:

- Visits to these establishments were prescribed, as were the conditions and durations of the exposures themselves. Today, of course, there is ongoing research to determine how and to what extent environmental factors such as temperature, natural and artificial light, and sound affect our health, and despite there having been some interesting conclusions, it is still an area of research that requires more investigation and exploratory trials.

Then, however, in the 1950s it was discovered that tuberculosis was only treatable through the use of antibiotics, and so architectural modernism – with its wide verandahs and flat roofs – lost its medical justification, so to speak. It became just another style to be mined for a new pastiche of superficial quirks and regional variations.

[Images: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier].

[Images: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier].

Even the siting of the project, in Mexico City, plays on this development. Early modern sanitariums and "health resorts," Nicollier writes, were designed with "specific needs regarding their site."

- Their regime of exposure to light, temperature, and clean air limited called for very particular climatic conditions falling within acceptable ranges. This is why the vast majority of these facilities were built in remote, rather idyllic locations near the coast or tucked away in alpine forests, away from any urban centers, which were considered to be too dense and dirty to be of any use for a treatment regime.

To wit, Thomas Mann's Magic Mountain.

Locating a facility like this, then, in Mexico City, a notoriously polluted megalopolis, is to suggest that architecture can counteract – that is, influentially avoid negation by – even the most invasive and unnatural of contexts. The building "supplements the environmental qualities of the city, incorporating them into its intensity gradients," in Nicollier's words.

[Images: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier].

[Images: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier].

But I find it almost overwhelmingly interesting to think that controlled exposure to a certain piece of architecture could actually be prescribed as a medical treatment. Viewed this way, the immersive experience of a well-designed space could actually stimulate one toward otherwise unknown medical highs and lows.

A building becomes almost pharmaceutical – or narcotic – in its level of influence over those who use it.

Could a building even become addictive?, one might ask. Could you experience something like withdrawal after going too long without experiencing it?

Might you literally someday receive a prescription from a doctor telling you to visit a certain building for twenty minutes, because the phenomenological impact of its vaulted galleries might cure you of whatever – kidney stones, anemia, or even manic-depression. Male pattern baldness. Sexual frigidity.

Space is the treatment for the things that harm you.

[Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier].

[Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier].

During Nicollier's thesis review, we discussed whether it might be possible for her building to act as a template or prototype for other such projects elsewhere. That is, could you produce a kind of spatial franchise in which certain combinations of color, materiality, texture, sequence, and even scent would be put to use for medical purposes? The light, sound, and temperature of the building would thus act as a general format, available to other designers in utterly dissimilar circumstances.

Perhaps it'd even be subject to regulation by the FDA and reproduced as a generic in Canada.

[Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier].

[Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier].

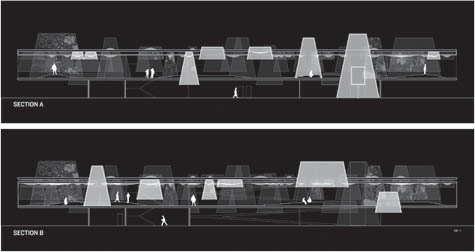

The sections, meanwhile, are beautiful in their own way –

[Images: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier].

[Images: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier].

– though I'm unashamedly a fan of the semi-psychedelic mood lighting of the actual models.

[Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier].

[Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier].

To read a complete description of the project and see larger images, check out this Flickr set of the project.

("Change of Heart" was produced at Rice University under the supervision of Dawn Finley, Eva Franch Gilabert, Farès el-Dahdah, and Albert Pope).

-----

Via BLDBLOG

Related Links:

Personal comment:

Je ne serais pas étonné d'apprendre que Marina Nicollier soit passée par un atelier de Philippe Rahm à l'EPFL, à Mendrisio ou à la AA, car le projet ressemble beaucoup à ce que j'ai pu voir en critique dans son atelier. Reste que le projet est intéressant et renvoie dans le fond à des architectures de type sanatorium!

Tuesday, January 20. 2009

The Wall paper house offers cheap dry home for poor and displaced

By Roger Boyes in Berlin

The house has built-in single and double beds and a veranda with a sealed-off area housing a shower and lavatory

Retailing for about $5,000 (£3,375), the house is supposed to brighten up Third World shantytowns and provide quick shelter for long-term refugees. The Universal World House can be used almost anywhere: light, easily assembled, environmentally friendly, earthquake-proof and, crucially in the age of recession, a bit of a bargain.

Gerd Niemoeller, its inventor, says that the 36sq m paper house weighs barely 800kg (1,763lb) — lighter than a VW Golf. “Without the foundation block, the whole house actually weighs in at about 400kg,” says the design engineer. It will not, however, simply blow away. The basic material is resin-soaked cellulose recovered from recycled cardboard and newspapers.

Add heat and pressure and the paper becomes extremely stable. The interior of the prefabricated building panels resemble honeycombs; an air vacuum fills each of the units. The result: a strong and stable exterior wall, well insulated. A similar construction technique is used in aircraft and high-speed yachts.

“But they are working with aluminium and other alloys, which is expensive, time consuming, energy intensive,” said Mr Niemoeller, who has patented the invention under the name of his Swiss-based company The Wall AG. “That’s not suitable for the Third World.” The prime purpose is to create intelligent housing settlements almost instantly for the displaced and the urban poor.

“People don’t want to flee their countries, they’ve been driven to leave their homes out of the need to survive,” said the 58-year-old engineer. “The number of migrants, refugees living in improvised housing, is going to grow with climate change, and we offer an alternative.” An alternative, that is, to the corrugated-iron sheds and lean-tos so often seen in the slums of the developing world.

The house has eight built-in single and double beds and a veranda with a sealed-off area housing a shower and a lavatory. It has been designed together with the German development aid agency GTZ, and with the architect Dirk Donath, from the Bauhaus University in Weimar.

Apart from the sleeping area, there are shelves, a table and benches. “It has been designed so that a family can slaughter an animal on the veranda, wash it in the shower and hang it, along with fish, on an integrated washing line.” The whole wall of the kitchen can be tipped open to let air in and to blur the distinction between inside and outside.

First inquiries have come from the Delta State oil developers in Nigeria, and from Angola. More than 2,000 houses have been ordered by another Nigerian company. Development aid agencies are considering whether the houses could be used to accommodate those fleeing from the cholera epidemic in Zimbabwe. South America, too, is interested.

The aim is to build the machines in northern Germany, near Kiel, and then send them, along with the raw materials, to the target country. The houses are then put together on the spot, creating local jobs and reducing transport costs.

But there is no reason why the paper houses should not be used in Europe.

The panels are rain resistant — and it is not compulsory to butcher a goat on the veranda.

-----

Via The Times Online

Personal comment:

Si vous souhaitez accéder à la propriété pour une somme modique! (reste encore le prix du terrain malgré tout...)

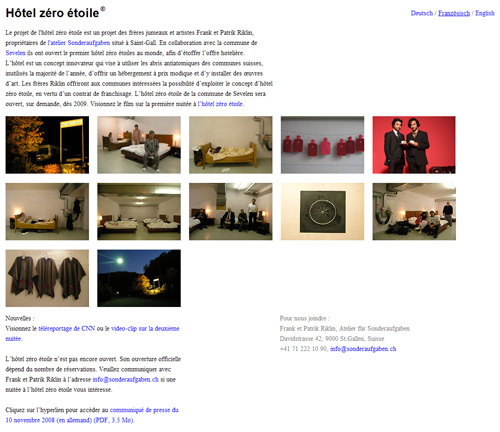

Motel 0

Dubai may have the only 7-star hotel, but Switzerland now has the only 0-star. In these modest times less luxurious accommodations may be preferred, so say hello to Null Stern Hotel, in St.Gallen, Switzerland. Via Dwell

-

-----

Via Archinect

Related Links:

Personal comment:

On en avait déjà entendu parler, il s'agit en réalité d'un projet d'artistes suisse-allemands. Mais l'hôtel reste fonctionnel, au cas où vous souhaiteriez passer une nuit pas chère ("confort minimum mais sécurité maximum") dans l'ancien abri-atomique d'une commune perdue!

Monday, January 19. 2009

Sky TV

[Image: From the series Cloud Projections by Blake Gordon].

[Image: From the series Cloud Projections by Blake Gordon].

Photographer Blake Gordon has been documenting the geometric effects of light pollution in Austin, Texas, capturing thinly defined shapes in the clouds, projected upward from the tops of buildings.

It's an accidental ornamentation of the city sky – or what Gordon calls Cloud Projections.

[Image: From the series Cloud Projections by Blake Gordon].

[Image: From the series Cloud Projections by Blake Gordon].

"I captured defined patterns of light above the city when atmospheric conditions were right," he explained in an email. This is part of a larger interest in seeing "the clouds as a surface." For instance, Gordon mentioned that he had also produced "rough images from a plane flight in Minnesota where I saw the reverse: low winter clouds gave light pollution a medium to mark upon, and towns broadcast their cluster signals to those above."

About these "broadcasts," Gordon asks: "Some of them were so precise that it's hard to conceive that they are just afterthoughts of a lighting design. Would it still be called light pollution?"

[Image: From the series Cloud Projections by Blake Gordon].

[Image: From the series Cloud Projections by Blake Gordon].

While I'm instantly reminded of Paul Virilio's War and Cinema – where Virilio memorably describes the Nazi use of searchlights as a form of temporary light-architecture, creating a "space" of monumental vaults and upward-projected walls to help define their night rallies – I'm also struck by at least two possibilities here:

1) Airplanes could project downward onto the cloud canopy, showing anything from television shows to the latest Hollywood blockbuster to local weather and temperature information. The audience? The people in that particular aircraft. Like some strange technological implementation of Jacques Lacan, you'd be moving forward into a world defined by your own projections. Imagine, though, looking out across the city at other airplanes stuck in holding patterns, projecting films down onto the clouds of their respective flight paths. You glimpse scenes from The Dark Knight, Valkyrie, and The Wrestler. Or perhaps planes could project images in all directions, forming cylinders of imagery. An IMAX of the sky. Whenever you encounter clouds, your flight crew switches on the outside projectors... and everyone gazes out at that ghostly presence, a dream-cloud of film passing hundreds of miles per hour through the inner atmosphere.

2) Buildings could project films upward onto the cloud canopy. For your next corporate party you hire SkyTV: a patented, cinematic approach to urban cloud cover. Drive-in cinemas would no longer exist; high-rises would, instead, have installed bleachers on their roofs, like those old tiered seats you find atop houses near Wrigley Field, put there so you can see the game without an official ticket. Only, here, those bleachers are tilted back like planetarium seats – and everyone is watching the sky.

- a) Even without shining films into the sky, this would be an amazing idea: turning the whole city into a planetarium. Perhaps astronomers should be asking: Why aren't there sky-bleachers on every roof? You're out on a date some night and you're invited to stop by a friend's party – but everyone seems to be heading up onto the roof. You both follow, drinks in hand – and soon you're out on the roofscape, nervous amidst bleachers, gigantic hulking silhouettes against the night sky. And there are dozens and dozens of people up there, reclined in near-silence, watching the constellations. There are thousands of buildings around the city like this, you're told. No one stays inside anymore.

b) Perhaps it's time to rethink movie theater design. Perhaps the coolest architecture studio you could take right now would be one in which you rethink the contemporary cinema. Perhaps the outdoor cinemas of the future use clouds as their surface, and rooftops as their arena. AMC might even offer corporate sponsorship. From GPSFILM to CINEMA41, ideas for redesigning the cinematic experience are already out there – so how might they be tweaked to involve the sky?

c) It's the summer of 2011 – a Friday night – and you're out for drinks in Manhattan with friends. But then all the lights in midtown begin to switch off, and weird glowing shapes appear in the sky. There are noises. You think it's some kind of cheesy night club opening up downtown, or perhaps the Mayan apocalypse a year early. But then: Ghostbusters III, projected from some kind of mega-projector, appears above you in the clouds. It's the world's most talked-about film premiere: ghosts in the sky and a million unticketed viewers, in a kind of vertical philanthropy of the moving image.

3) Like something out of Archigram, you develop a stationary airship that passes up through the clouds each night to project films back down; for the audience below, it's as if a talking hologram has settled into the sky above the city. The people who control the ship are dream technicians. But then the airship is hijacked by a 15-year old, who flies it above remote stretches of the Amazon, terrifying uncontacted native tribes. Steven Spielberg soon makes a movie about him, produced by Werner Herzog.

4) BLDGBLOG here proposes FogFilms, a new project for my fellow San Franciscans. When the fog gets bad, the films get going.™ We'll transform fog banks into film screens.

In any case, it seems worth asking if we could transform light pollution from its current status as a kind of abstract blur, somewhere between orange and white, into something worth watching – if we could focus it, concentrate it, or, more accurately, give it content.

[Image: Andrea Mantegna, Oculus in the Camera degli Sposi].

[Image: Andrea Mantegna, Oculus in the Camera degli Sposi].

After all, there would seem to be serious architectural possibilities here. On foggy nights, or humid nights, or cloudy nights, you transform the sky into a trompe l'oeil painting, a cinematic oculus, a new ceiling, a kind of dream-valve above the city.

-----

Via BLDBLOG

Related Links:

Personal comment:

Pas tout à fait d'accord avec les propositions faites par Geoff Manaugh (BLDBLOG) --après tout, les projections dans le "fog" datent (au minimum) du milieu des années 70 et du fameux "Line defining a cone" d'Anthony Mc Call! puis ont été popularisées par Michael Jackson himself dans ses clips avant d'être expérimentées par tout le monde en club ou concert! ... Et je pense que ce ne serait pas très intéressant d'être confronté à un "tv-sky" (ou même des projections de films). Il y aurait bien sûr par contre des projets spécifiques à développer. En ce sens, le travail de Lozano-Hemmer est probablement plus intéressant ou donne une piste plus architecturale pour des projections volumiques.

Le travail du photographe Blake Gordon (Cloud Projections), qui documente une sorte de "cité hantée", tout en ombres et lumières est par contre intéressant.

Wednesday, January 14. 2009

Choosing What Our Cities Will Look Like in a World Without Oil

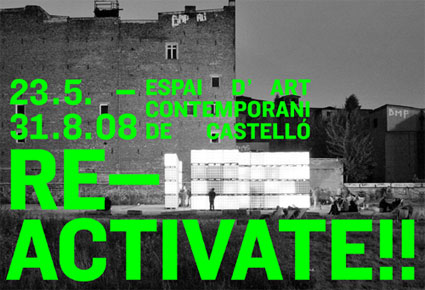

As announced two days ago, here's a lengthier report about REACTIVATE!! Espacios remodelados e intervenciones mínimas (Remodeled spaces and minimal interventions), an exhibition which takes place until August 31 at the Espai d' Art Contemporani de Castelló, an hour away from Valencia.

View of the exhibition. Image courtesy of the Espai d' Art Contemporani

If we start now, we can choose what we want our cities to look like in the future. We can make them the resilient, sustainable centers of culture, justice, art and creativity that we hope they will become.

Author and Professor Peter Newman is asking us to imagine and then get to work building these urban centers. His book and talk, both titled Resilient Cities: Responding to Peak Oil and Climate Change, ask audiences to honestly look at what will happen to our cities when we reach Peak Oil. During his 90 minute presentation last night at Seattle's City Hall, Newman explained to the full house how peak oil will soon change reality as we know it; and how if we choose to make it so, we can take this challenge as our opportunity to create a functional, just and sustainable world.

Picturing a future where we do nothing resulted in some frightening scenarios: ones where we are barely getting by and injustice is running rampant. But, as Newman explained, picturing a future in which we respond to the challenge by building resilient cities results in images of a flexible and supportive, flourishing society.

|

“We need both at the same time," Newman said. "Or they will undermine what we need to do together.”

Here are a few exceptional points, summarized from Newman's worldchanging presentation:

End Agglomeration Diseconomies

The freeway is a failed technology. Freeways don’t actually ultimately help people get where they want to go any faster; they simply scatter people and economies. Freeways fail as public spaces; as infrastructure, they are dinosaurs. Their impact on cities is not good for economics or people. So we should stop building them. We should instead organize and advocate for rail systems so we can reclaim and rehabilitate our open spaces. Car-dependent cities can begin to reclaim freeways by investing in rail transit and building up local economies around station hubs.

Density, Walkability and Affordable Housing

High quality, high rise developments in the city will increase walkability, and decrease the number of trips taken by car. These developments will function best if developers work in partnership with land use planners. To end the division and disagreements that high density development creates, we have to require all developments to allot 15 percent of space to social housing, and require 5 percent of the value of a development to go toward social infrastructure, like landscaped open-to-the-public space, public art, community centers, schools, arts facilities.

Complete Streets, Smart Grids

Cars won’t go away completely, even though the oil we currently use to power them will. The cars of the future will run on alternatively produced electricity. We can link the extra energy produced from solar and wind production systems to the batteries in our cars with Smart Grids. These energy linking systems help buildings and transportation power each other. (Read more about Smart Grids on Worldchanging here and here.)

Eco-villages colonizing the fringe

Build eco-villages on the outskirts of the urban ring. Built with their own water, power and sewage systems, we can turn the crumbling suburbs into self sustaining eco-communities of the future.

What We Need to do Now

Newman gave vibrant examples of each of these ideas happening in cities all over the world, from Seoul to London, Copenhagen to Vancouver, B.C., these cities are proving that this is possible. All we need now, said Newman, is imagination, post oil strategies, partnerships and demonstrations, and above all HOPE!

Let’s get to work.

-----

Via Worldchanging

Related Links:

Personal comment:

Re-activate, une exposition (dont on a déjà parlé dans ce blog) mise sur pied par le Schweizerisches ArchitekturMuseum de Bâle est ici ré-activée (...) à valence. Ce qui nous intéresse ici est plutôt le compte rendu de la conférence du Prof. Peter Newman qui parle de la ville du "peak oil" et du "climate change": Resilient cities

(Page 1 of 3, totaling 13 entries)

» next page

fabric | rblg

This blog is the survey website of fabric | ch - studio for architecture, interaction and research.

We curate and reblog articles, researches, writings, exhibitions and projects that we notice and find interesting during our everyday practice and readings.

Most articles concern the intertwined fields of architecture, territory, art, interaction design, thinking and science. From time to time, we also publish documentation about our own work and research, immersed among these related resources and inspirations.

This website is used by fabric | ch as archive, references and resources. It is shared with all those interested in the same topics as we are, in the hope that they will also find valuable references and content in it.