Tuesday, February 23. 2010

Tiré d'un post plus long sur Mammoth à propos des glaciers --

(...)

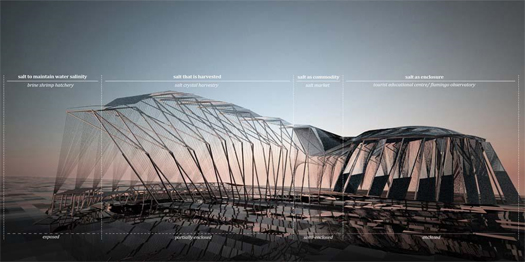

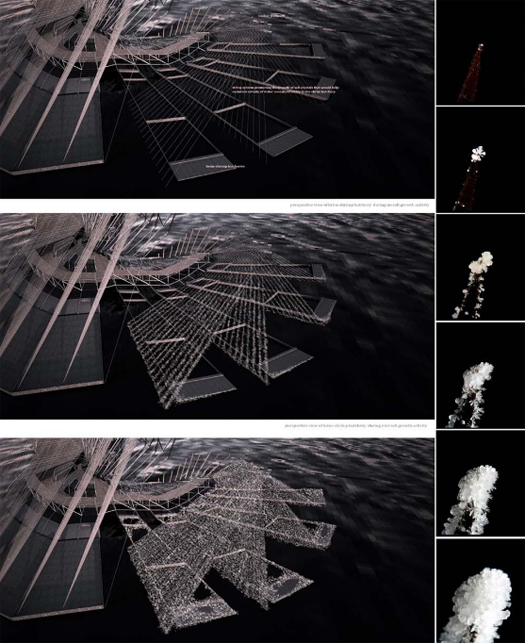

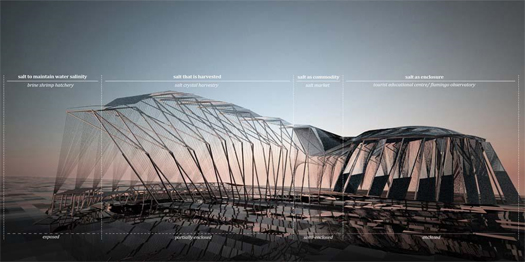

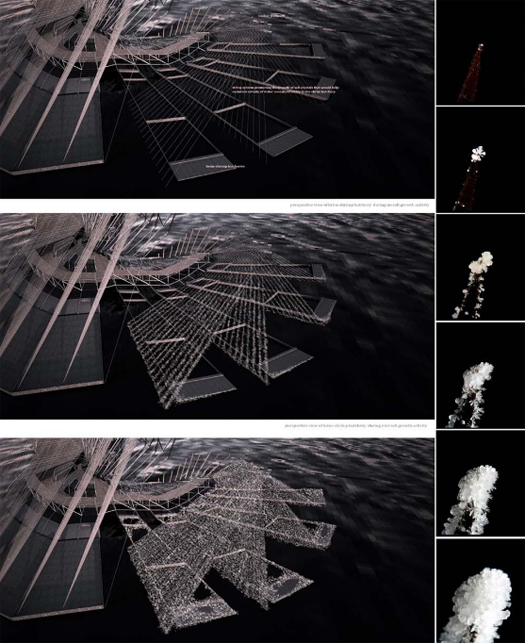

Wen Ying Teh’s “An Augmented Ecology of Wildlife and Industry”, a RIBA President’s Medal winning project last year, proposes a hybrid structure — part building, part extension of the ecological process of a saline lagoon — which could be inserted into one of the salt mines near Puerto Ayora, supporting the salt mining industry while restoring the ecological balance of the saline lagoon, drawing Greater Flamingos back to Santa Cruz.

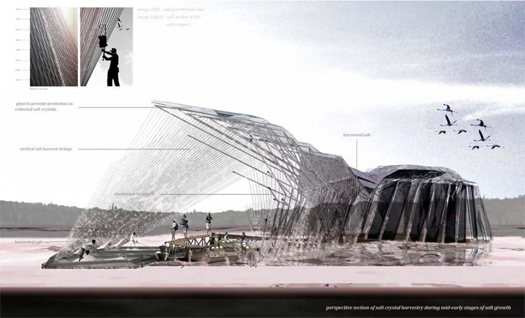

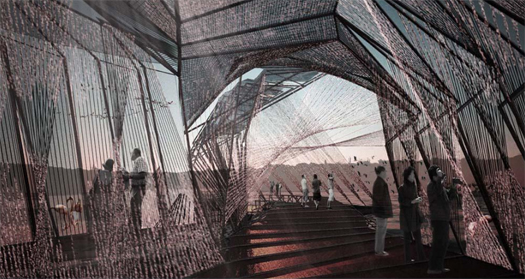

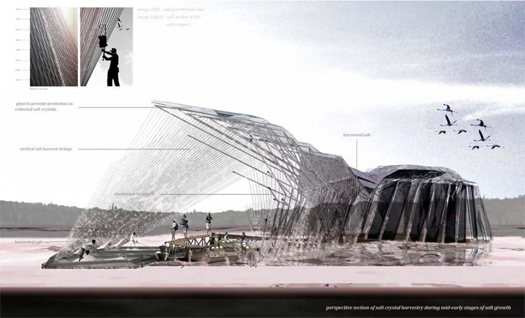

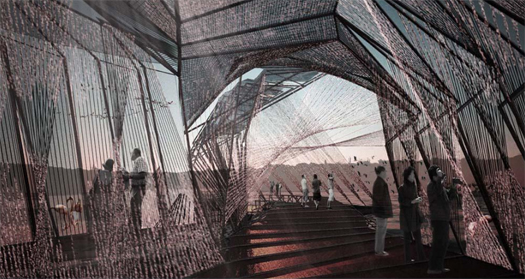

The structure, which hosts a brine shrimp hatchery, salt crystal harvestry, salt market, tourist education center, and flamingo observatory, protrudes linearly into the lagoon before fanning out into a series of tanks housing the brine shrimp. The skin of the structure is composed of hanging nylon threads, which wick salt from the lake through capillary action, crystallizing a mineral skin that is cyclically harvested by the salt miners, so that the building pulses through the seasons with the wax and wane of sodium chloride. Because the miners no longer need to disturb the lagoon to harvest salt, the natural balance of the lagoon can be restored.

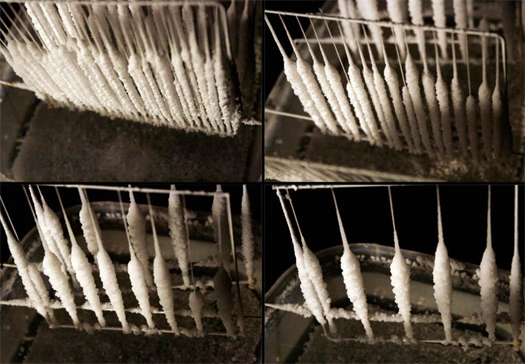

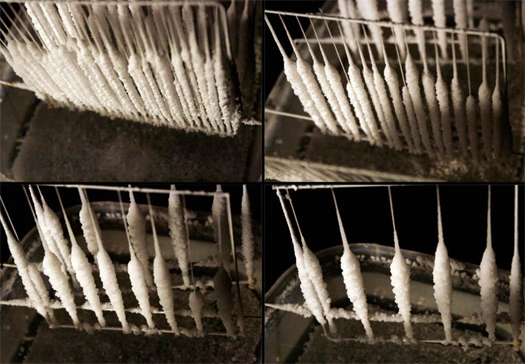

Wen Ying Teh conducted physical experiments at scale to test the proposed nylon fiber system and the capillary deposition of salt upon the system.

The cyclical growth of the salt skin, shown over the shrimp tanks.

In Wen Ying Teh’s project, the building itself is constituted by processes of accretion and erosion: salt accretes to form the skin through capillary action, and then is eroded, both by harvesting and by rain, with the latter process of erosion being tied into the maintenance of proper salinity for the shrimp hatchery. The structure serves as an extension of the lacustrian ecosystem, not just physically, but in time and process. While in some ways this is an amplification of processes that already occur on buildings — eroding as they weather, accreting objects, paints, memories, and so on as they’re occupied and augmented and built upon — making accretion and erosion not just ancillary to the architecture, but central to it, remains an unusual and beautiful approach.

I first saw Ying’s project at dpr-barcelona; Ying’s tutors were Kate Davies and Liam Young, of the always-interesting Tomorrow’s Thoughts Today.

-----

Via Mammoth

by jared.langevin@gmail.com (Jared Langevin)

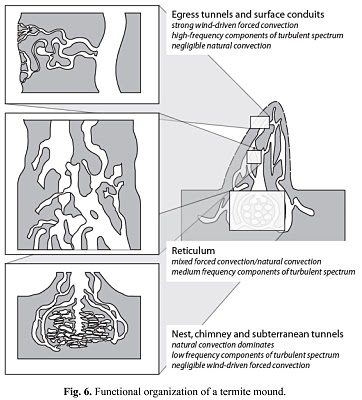

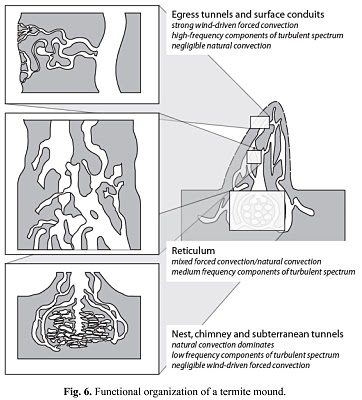

Today's New Scientist features a fascinating piece about termite mounds' relevance to sustainable architecture as physical interventions that achieve entirely passive means of conditioning, while also being beautiful and actively providing for the sustenance of their inhabitants. The mounds have been an oft-cited source of bio-inspired building design (see the Eastgate Center), but new knowledge suggests that much more is at work in their passive environmental controls than a simple stack effect, and that in fact their construction acts more like a giant lung for gas exchange. An excerpt from the article:

This is very different to the way ventilation works in modern human buildings. Here, fresh air is blown in through vents to flush stale air out. Turner thinks there is something to be gleaned from the termites' approach. "We could turn the whole idea of the wall on its head," he says. We should not think of walls as barriers to stop the outside getting in, but rather design them as adaptive, porous interfaces that regulate the exchange of heat and air between the inside and outside. "Instead of opening a window to let fresh air in, it would be the wall that does it, but carefully filtered and managed the way termite mounds do it," he says.

Be sure to read more here and to take a look at the links included in the article for more detailed information.

------

by noreply@blogger.com (Geoff Manaugh)

A mind-bogglingly awesome new project from MIT called Flyfire hopes to use large, precision-controlled clouds of micro-helicopters, each carrying a color-coordinated LED light, to create massive, three-dimensional information displays in space.

[Image: Via Flyfire]. [Image: Via Flyfire].

Each helicopter is "a smart pixel," we read. "Through precisely controlled movements, the helicopters perform elaborate and synchronized motions and form an elastic display surface for any desired scenario." Emergency streetlights, future TV, avant-garde rural entertainment, and even acts of war.

Watch the video:

Instead of a drive-in cinema, in other words, you could simply be looking out from the windscreen of your car at a massive cloud of color-coordinated, precision-timed, drone micro-helicopters, each the size and function of a pixel. Imagine planetarium shows with this thing!

The Flyfire canvas can transform itself from one shape to another or morph a two-dimensional photographic image into an articulated shape. The pixels are physically engaged in transitioning images from one state to another, which allows the Flyfire canvas to demonstrate a spatially animated viewing experience.

Imagine web-browsing through literal clouds of small flying pixels, parting and weaving in the air in front of you like fireflies (or imagine training fireflies to act as a web browser). You're in a university auditorium one day when, instead of delivering her projected slideshow, your professor simply remote-controls a whirring vortex of ten thousand flying micro-dots. Digital 3D cinema is nothing compared to this murmuration of light.

Channeling Tim Maly, we might even someday see a drone-swarm of LED-augmented, artificially intelligent nano-helicopters flying off into the desert skies of the American southwest, on cinematic migration routes blurring overhead. On a lonely car drive through northern Arizona when a film-cloud flies by...

An insane emperor entertains himself watching precision-controlled image-clouds, some of which are distant satellites falling synchronized through space.

-----

Via BLDGBLOG

Personal comment:

D'une façon différente (écran, images volumiques et donc display), cela me fait penser au projet de Nicolas Reeves ("Mescarillons", self assembling architecture) et à ce que nous imaginions au début du projet de recherche Variable_Environment autour de la création d'architectures variables exploitant des "swarm intelligent flying robots"... Impossible à l'époque.

by noreply@blogger.com (Geoff Manaugh)

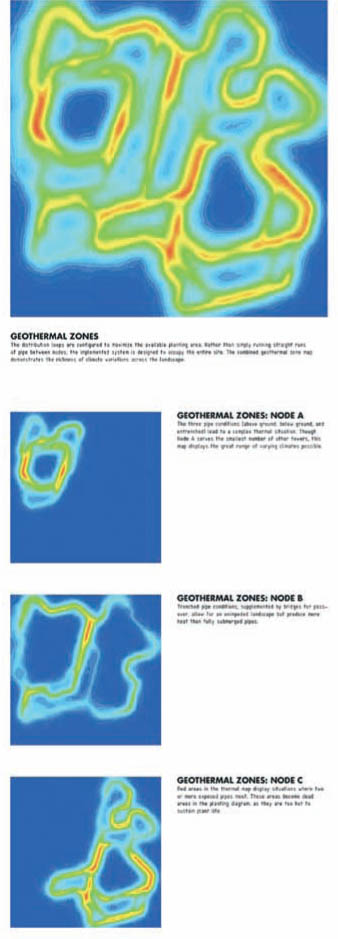

[Image: "Reykjavik Botanical Garden" by Andrew Corrigan and John Carr]. [Image: "Reykjavik Botanical Garden" by Andrew Corrigan and John Carr].

In a fantastic issue of AD, edited by Sean Lally and themed around the idea of "Energies," a long list of projects appeared that are of direct relevance to the Glacier/Island/Storm studio thread developing this week. I want to mention just two of those projects here.

[Image: "Reykjavik Botanical Garden" by Andrew Corrigan and John Carr]. [Image: "Reykjavik Botanical Garden" by Andrew Corrigan and John Carr].

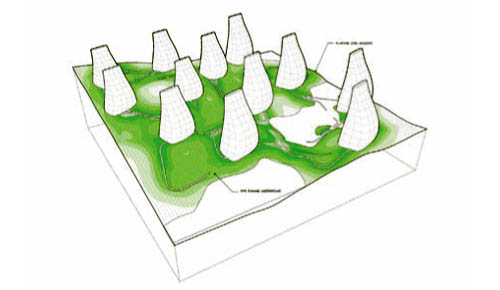

For their "Reykjavik Botanical Garden," Rice University architecture students Andrew Corrigan and John Carr proposed tapping that city's geothermal energy to create "microclimates for varied plant growth."

"Heat is taken directly from the ground," they write, "and piped up across the landscape into a system of [pipes and] towers."

Zones of heat radiate out from the pipes, creating a new climate layer with variable conditions based on their number and proximity to each other. These exterior plantings are mostly native to Iceland, but the amplified environment allows a wider range of growth than would normally be possible, informing the role and opportunity of this particular botanical garden. Visitors experience growth never before possible in Iceland, and travel through new climates throughout the site.

Amidst "hydroponic growing trays and research laboratories," and sprouting in the climatic shadow of complicated "air-intake systems," a new landscape grows, absorbing its heat from below.

[Image: "Reykjavik Botanical Garden" by Andrew Corrigan and John Carr]. [Image: "Reykjavik Botanical Garden" by Andrew Corrigan and John Carr].

The climate of the city is altered, in other words, literally from the ground up; using the functional equivalent of terrestrially powered ovens, otherwise botanically impossible species can healthily take root.

This domestication of geothermal energy, and the use of it for purposes other than electricity-generation, raises the fascinating possibility that heat itself, if carefully and specifically redirected, can utterly transform urban space.

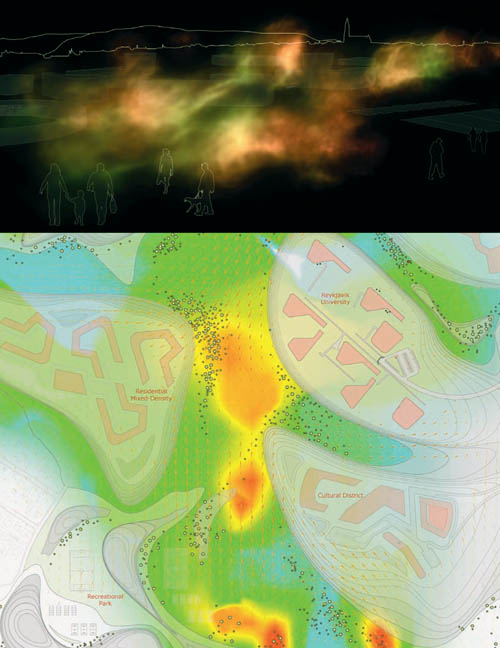

[Image: Produced for the "Vatnsmyri Urban Planning Competition" by Sean Lally, Andrew Corrigan, and Paul Kweton]. [Image: Produced for the "Vatnsmyri Urban Planning Competition" by Sean Lally, Andrew Corrigan, and Paul Kweton].

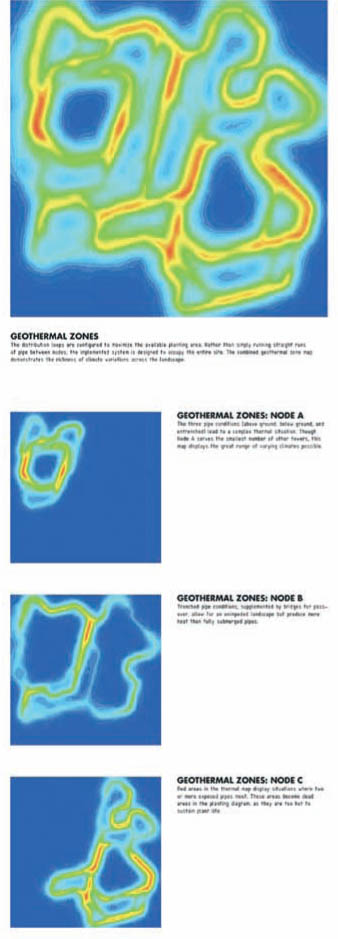

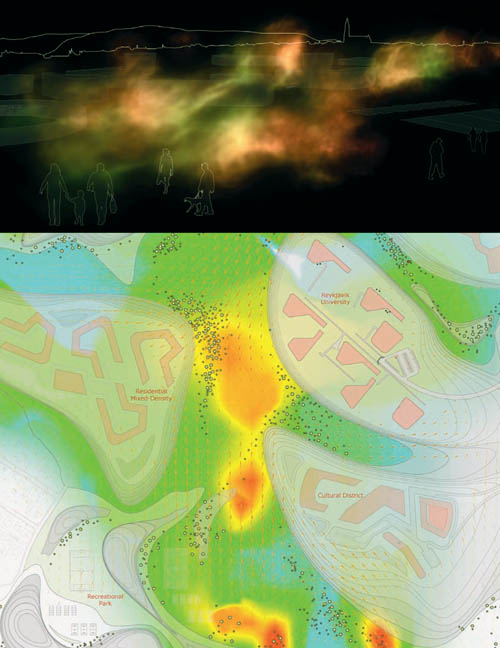

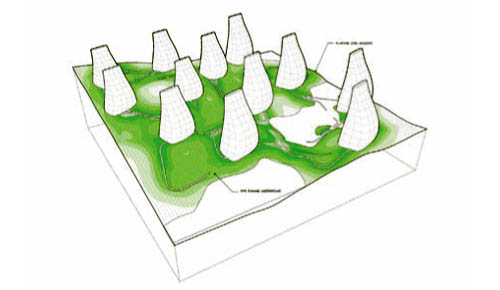

A variant on this forms the basic idea behind Sean Lally's own project, produced with Andrew Corrigan and Paul Kweton, for the Vatnsmyri Urban Planning Competition (a competition previously discussed on BLDGBLOG here).

Their design also proposes using geothermal heat in Reykjavik "to affect the local climatic conditions on land, including air temperature and soil temperature for vegetative growth." But their goal is to generate a "climatic 'wash'"—that is, an amorphous zone of heat that lies just slightly outside of direct regulation. This slow leaking of heat into the city could then effect a linked series of hot zones—or variable microclimates, as the architects write—that would punctuate the city with thermal oases.

Like a winterized inversion of the air-conditioned cold fronts we feel rolling out from the open doors of buildings all summer long, this would be pure heat—and its attendant humidity—roiling upward from the Earth itself. The result would be to generate a new architecture not of walls and buildings but of temperature thresholds and bodily sensation.

Indeed, as David Gissen suggests in his excellent book Subnature, this project could very well imply "a new form of urban planning," one in which sculpted zones of thermal energy take precedence over architecturally designated public spaces.

Of course, whether this simply means that under-designed urban dead zones—like the otherwise sorely needed pedestrian parks now scattered up and down Broadway—will be left as is, provided they are heated from below by a subway grate, remains, for the time being, undetermined.

This is all just part of a much larger question: how we "renegotiate the relationship between architecture and weather," as Jürgen Mayer H. and Neeraj Bhatia, editors of the recent book -arium: Weather + Architecture, describe it. The Glacier/Island/Storm studio will continue to explore these and other abstract questions of climate and architectural design throughout the spring.

-----

Via BLDGBLOG

|

[Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: "Reykjavik Botanical Garden" by Andrew Corrigan and John Carr].

[Image: "Reykjavik Botanical Garden" by Andrew Corrigan and John Carr]. [Image: "Reykjavik Botanical Garden" by Andrew Corrigan and John Carr].

[Image: "Reykjavik Botanical Garden" by Andrew Corrigan and John Carr]. [Image: "Reykjavik Botanical Garden" by Andrew Corrigan and John Carr].

[Image: "Reykjavik Botanical Garden" by Andrew Corrigan and John Carr]. [Image: Produced for the "Vatnsmyri Urban Planning Competition" by Sean Lally, Andrew Corrigan, and Paul Kweton].

[Image: Produced for the "Vatnsmyri Urban Planning Competition" by Sean Lally, Andrew Corrigan, and Paul Kweton].