Friday, July 31. 2009

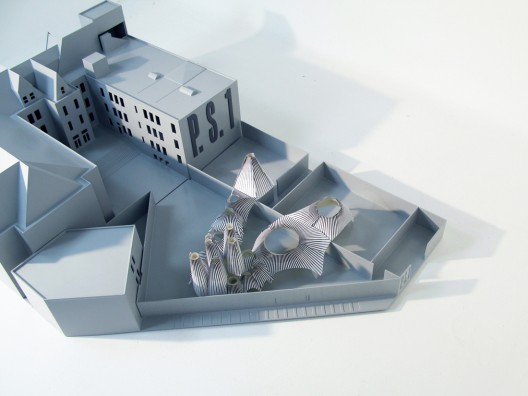

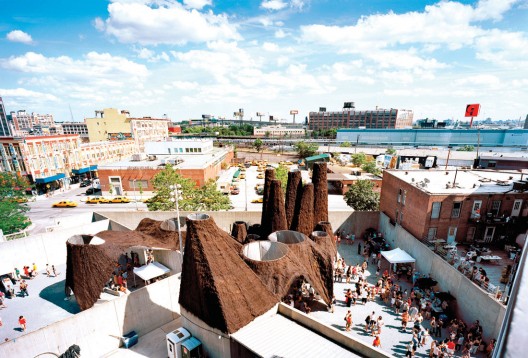

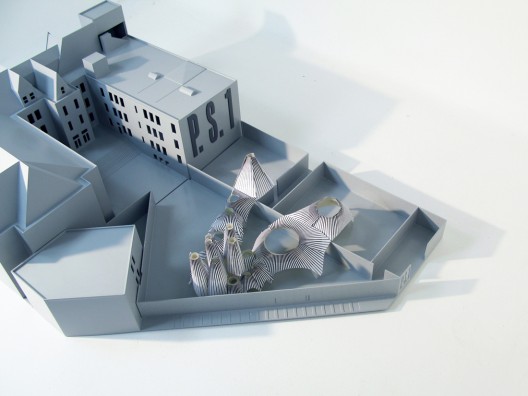

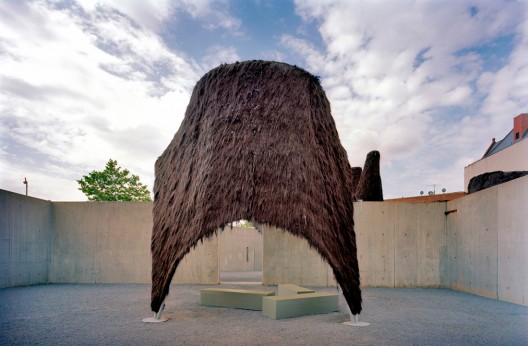

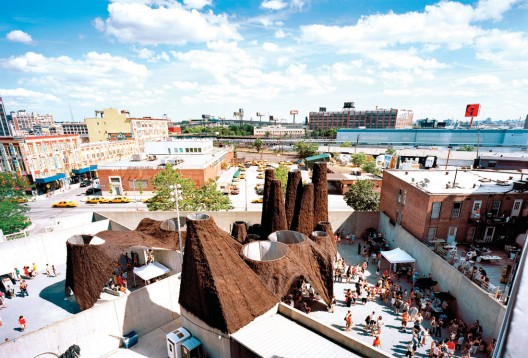

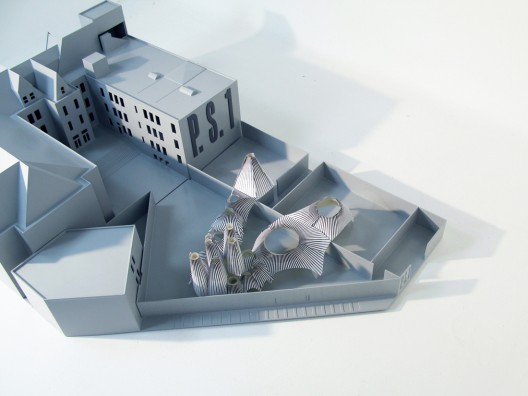

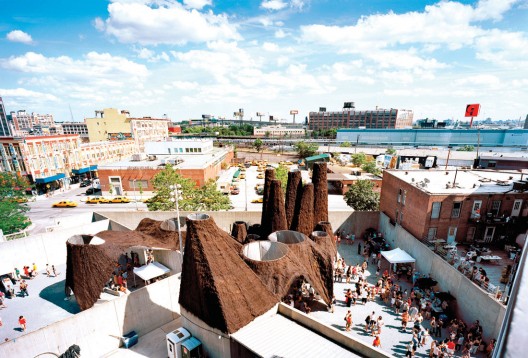

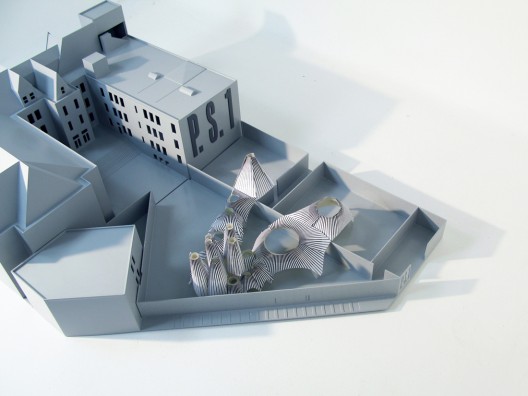

A few months ago we presented you the winning entry for this years YAP competition for the P.S.1 summer installation, awarded to MOS Architects (Michael Meredith, Hilary Sample) as we reported earlier.

This competition has been a field for experimentation on digital manufacturing, new materials and new construction techniques -all under a tight budget-, as we saw in 2008 with the P.F.1 by WORKac.

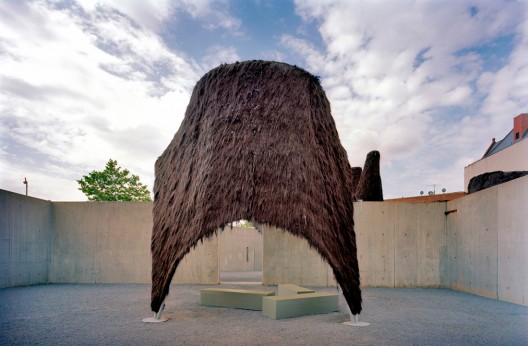

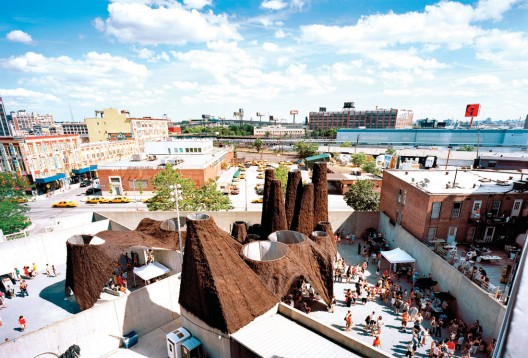

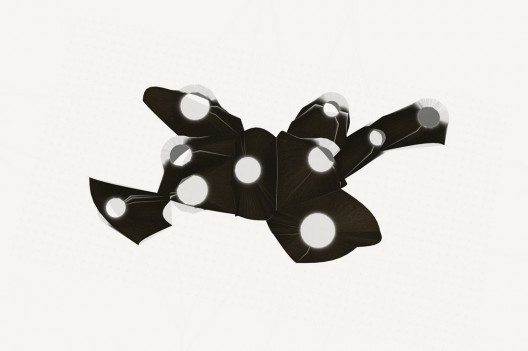

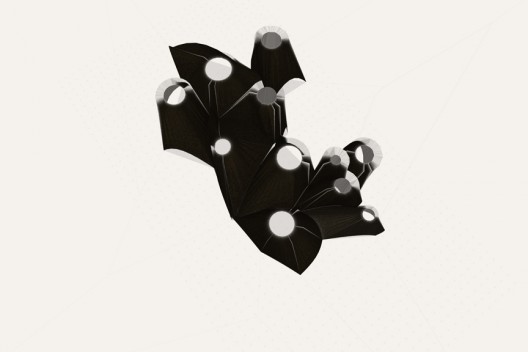

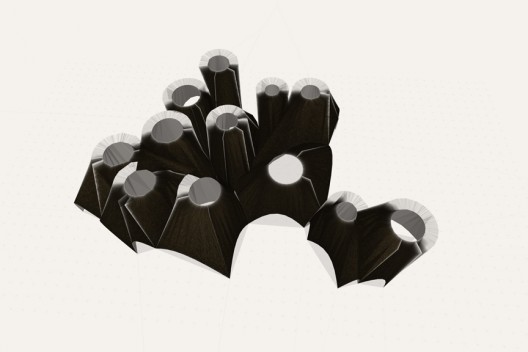

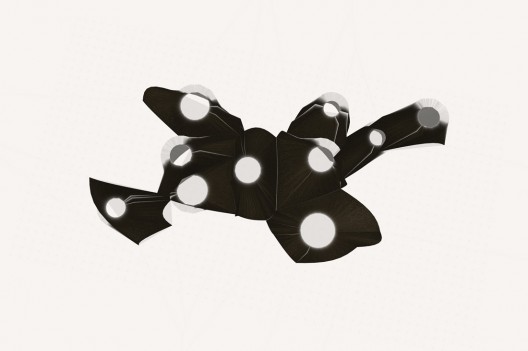

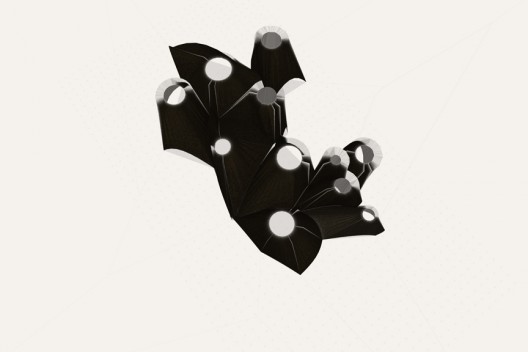

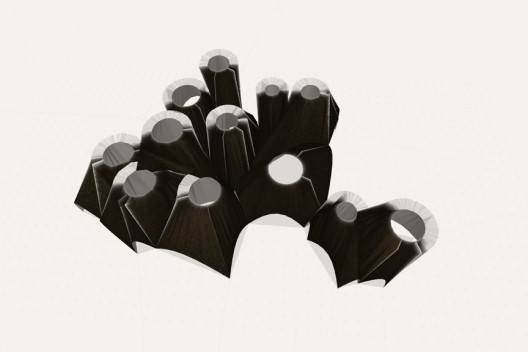

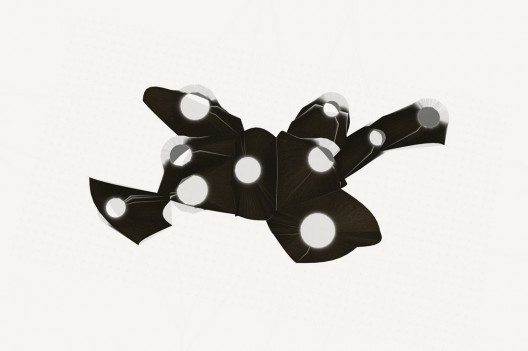

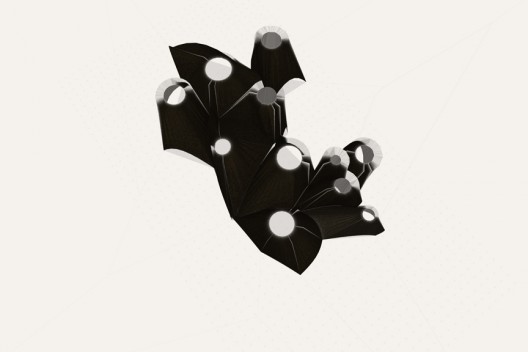

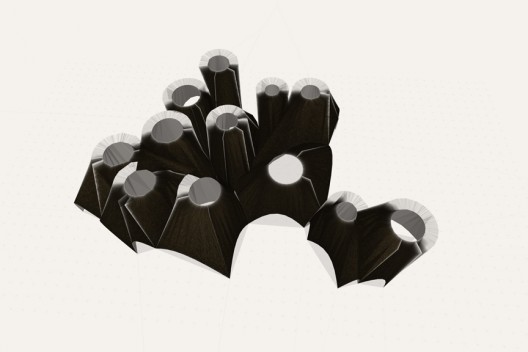

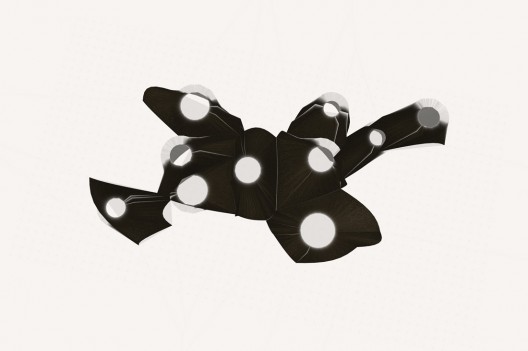

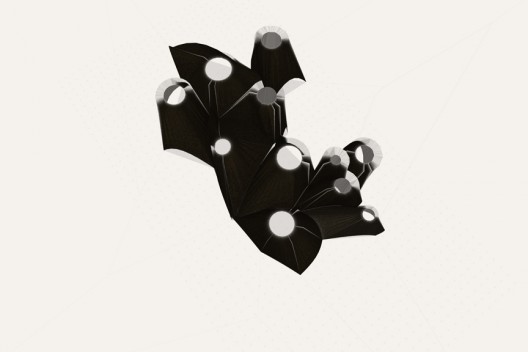

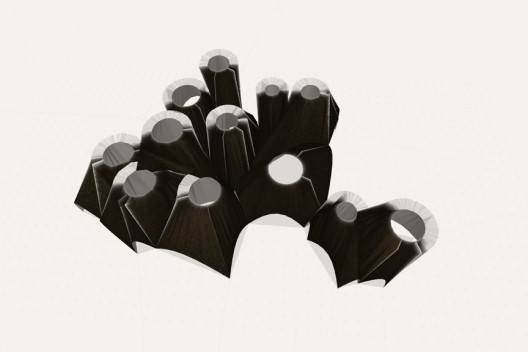

To keep the courtyard fresh, a series of “hut” like structures conformed by inverted catenaries (part of an on going research by the practice) acting as chimneys: The faux fur that covers them collects heat from the sun, transfering it to the air inside the huts creating a chimney effect that keeps air flowing to cool the lower level.

The resulting space corresponds to the after-party concept envisioned by MOS:

The main purpose of the afterparty is to provide a relaxing environment, as compared to the earlier venue, where the atmosphere is usually more frenetic. During an afterparty people often sit down, relax, and chat freely, meet new people in a more controlled setting. If the original party was one that continued until late at night, the afterparty will often include a morning snack, which usually counts as breakfast. …. Possibly in contrast to relaxation, the afterparty can provide a chance for people to get away from the eyes of people who were overseeing the main party. This tends to be more common in events such as school balls where alcohol consumption is not allowed, and provides a location where the partygoers will be allowed to drink. In this case, the afterparty may turn out to be more lively than the main party, as the people are freed from the restrictions that were placed on them during the main party.

All photos by © Florian Holzherr. See more after the break:

-----

Via ArchDaily

Personal comment:

Un mélange entre hi-tech génératif (+ ou -) et vernaculaire (+ ou - tentes nomades mongoles (?)), avec un discours sur la gestion des fluxs thermiques évoquant clairement les "architectures sans architectes".

Et un exemple de plus de l'utilisation renouvelée des pavillons comme support de statements (traditionnel celui-ci, puisque le PS1 de New York est un des premiers à avoir relancé le style).

A few months ago we presented you the winning entry for this years YAP competition for the P.S.1 summer installation, awarded to MOS Architects (Michael Meredith, Hilary Sample) as we reported earlier.

This competition has been a field for experimentation on digital manufacturing, new materials and new construction techniques -all under a tight budget-, as we saw in 2008 with the P.F.1 by WORKac.

To keep the courtyard fresh, a series of “hut” like structures conformed by inverted catenaries (part of an on going research by the practice) acting as chimneys: The faux fur that covers them collects heat from the sun, transfering it to the air inside the huts creating a chimney effect that keeps air flowing to cool the lower level.

The resulting space corresponds to the after-party concept envisioned by MOS:

The main purpose of the afterparty is to provide a relaxing environment, as compared to the earlier venue, where the atmosphere is usually more frenetic. During an afterparty people often sit down, relax, and chat freely, meet new people in a more controlled setting. If the original party was one that continued until late at night, the afterparty will often include a morning snack, which usually counts as breakfast. …. Possibly in contrast to relaxation, the afterparty can provide a chance for people to get away from the eyes of people who were overseeing the main party. This tends to be more common in events such as school balls where alcohol consumption is not allowed, and provides a location where the partygoers will be allowed to drink. In this case, the afterparty may turn out to be more lively than the main party, as the people are freed from the restrictions that were placed on them during the main party.

All photos by © Florian Holzherr. See more after the break:

-----

Via ArchDaily

Personal comment:

Un mélange entre hi-tech génératif (+ ou -) et vernaculaire (+ ou - tentes nomades mongoles (?)), avec un discours sur la gestion des fluxs thermiques évoquant clairement les "architectures sans architectes".

Et un exemple de plus de l'utilisation renouvelée des pavillons comme support de statements (traditionnel celui-ci, puisque le PS1 de New York est un des premiers à avoir relancé le style). Les projets de MOS sont à regarder sur leur site, tout cela a l'air assez intéressant.

Tuesday, July 28. 2009

Urban Farming and Apocalypse Chic

"Architects should be busying themselves with making a post-crisis future appealing, and doing so in a way that stretches beyond putting in a turntable. The model should be post-War planning, utopianism, not Waterworld. The future should be well-made and attractive." [Spillway]

-----

Via Pruned (links)

Personal comment:

En partie à propos de l'installation d'EXYZT & Agnes Denes (recréation de la pièce "Wheatfield - A Confrontation") durant l'exposition Radical Nature au Barbican de Londres.

Friday, July 24. 2009

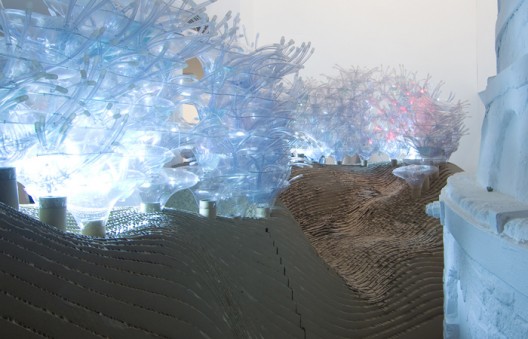

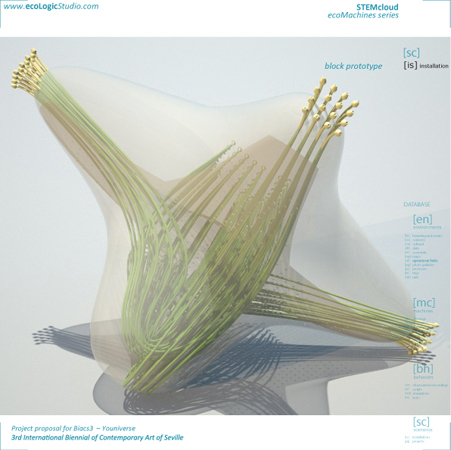

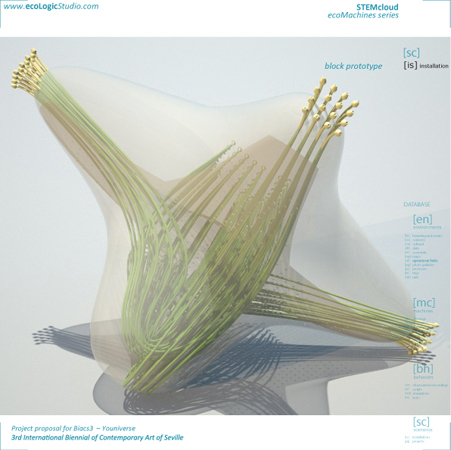

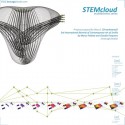

After meeting Claudia Pasquero and Marco Poletto, founders of ecoLogicStudio at the Beyond Media Festival in Florence, they talked to us about one of their latest projects, the STEMcloud v2.0 that now we want to share here, as is a really new and avant-garde vision about parametric and genetic architecture and the way that human interaction can bring new life to architecture projects:

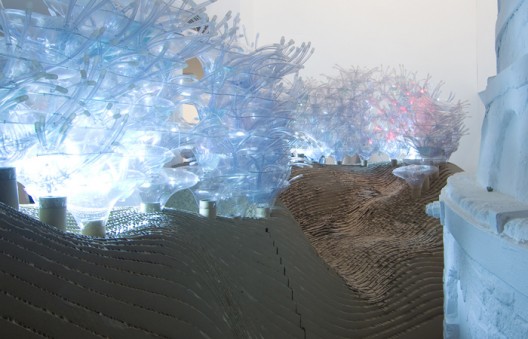

The STEMcloud v2.0 project proposes the development and testing of an architectural prototype operating as an oxygen making machine. The project has been presented and designed for the SEVILLE ART and ARCHITECTURAL BIENNALE 2008.

STEMcloud v2.0 technological matrix will operate as a breeding ground for micro-ecologies found in the local river of Seville, the Guadalquivir, and will involve the public in the breeding process. The transparency and porosity of the architectural system allows the process to be visually and materially exposed and interfere with the microclimate of the gallery; the public will feed the colonies present in the river water with nutrients, light and CO2 and as a result oxygenate the gallery space; the growth process will be triggered by patterns of interaction with the public and in turn will affects these patterns with its visual effects. Multiple feedback cycles are provoked within the components of the system, with the gallery environment and within the city itself.

This extended model of systemic architecture can be framed and understood in cybernetic terms as a multilayer crossing of feedback loops; cybernetics provides an operational framework to deal with change and transformation, the two main defining qualities of our new ecologic understanding of architecture; the starting point of the experiment is artificially defined by us and provides what scientist call a primed condition necessary to promote interaction.

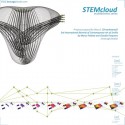

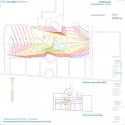

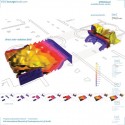

The cybernetic loops

The basic cybernetic set for the Seville experiment includes 3 components: the urban environments (the river ecology and the gallery space), the architectural machine (STEMcloud) and human behaviour (the visitors). These systems are multilayered and diverse and they will interact in a variety of ways: in this sense we can consider the experiment as complex and the outcome of it unpredictable. It is impossible to tell what kind of equilibrium will emerge within each of the 3 systems; what kind of algae ecologies will grow? How will visitors be reacting to them? In the impossibility of control the experiment is about communication: STEMcloud is organized to allow and promote communication among the systems in such a way that a conversation/learning process could emerge. Visitors will be transformed in ecologists, the STEM blocks into microhabitats, the gallery into an oxygenating garden or, perhaps, laboratory. The priming of the system and the channels of communication between systems have been carefully designed and engineered and can be summarized as a series of feedback loops within the more generic cybernetic set previously described.

Machinic feedback cycle 1: organic growth in relationship to radiation field

Wide spectrum light is positioned strategically to generate a radiation field, kept constant in time. Algae growth is stimulated by the field and will respond to it; feedback arises while each block develops his own internal equilibrium.

Machinic feedback cycle 2: organic growth in relationship to nutrients concentration

Nutrients is inserted into the system to prime its starting condition. More active blocks will consume more nutrients and grow faster. Overgrown blocks will be more opaque to light affecting the radiation field. Coordination between nutrient and radiation will push the differentiation further.

Machinic feedback cycle 3: oxygenation to frequency of use

Photosynthetic activity will be monitored live and visually fed back to the user. More active block will signal the need to be fed with CO2 provided by the user. Users will respond to visual clues (LED intensity) and trigger modifications with their action.

-----

Via ArchDaily

Personal comment:

L'intégration de flux/échanges biologiques dans le bâtiment: production d'oxygène et échanges énergétiques (pouvant potentiellement rafraîchir, chauffer, etc.) est une piste intéressante.

Wednesday, July 22. 2009

by Lisa Stiffler

Ripples, and sometimes waves, of the economic tsunami continue to roil through cities across the United States. One product of the downturn is stalled real estate projects. Many shelved projects have left vacant lots, derelict buildings, or parking lots where housing or office space was planned. The need to put these spaces back into use has motivated some great thinking about how to integrate open space and farming into the urban landscape. Interestingly, this is not a new problem. Philadelphia has been working on projects to convert “brown space” to “green space” for years. Philadelphia’s voids were created by migration from the cities to outlying urban areas, not a specific downturn. In 2005 they held an international design competition called Urban Voids. The point is, Philly has paved the way—er, broken new ground—for other cities to follow. And the best ideas about what to do with vacant property have to do with food.

You can review some of the design contest entries here. For the most part these ideas are at the edge of feasibility, but that’s the point of design competitions: to push the limits of what conventional wisdom says is possible.

One of the successful entries to the Urban Voids competition was Front Studio’s cleverly named Farmadelphia concept. Farmadelphia was another competition created to generate ideas for urban agriculture in empty urban spaces.

Here is an aerial view.

Some more detailed images. Here is a pasture for urban cows.

We wouldn’t want to leave out the chickens.

What is a farm with out some goats?

Farmadelphia knits together a couple of ideas we’ve discussed about urban farming and food insecurity. Specifically Farmadelphia challenges us to consider the end of the dichotomy between rural and urban. This idea of connecting farming with urban life is not new to the Northwest. And new doors are opening as urban properties remain undeveloped.

Seattle’s Greg Smith has allowed a great food truck to park right around the corner from the Sightline offices on property that is no longer going to be developed. Portland has been doing this for years. Seattle, Portland and Vancouver allow chickens and thanks to City Councilmember Richard Conlin Seattle allows goats.

Seattle has a municipal farm, the Marra Farm, that is not only in an urban area but in part of the city that’s downright industrial, South Park. The Marra Farm is a working farm that is right near the day-lighted Hamm Creek. The Marra Farm was one of the many farms operated by Italian immigrants in the Duwamish River Valley that supplied produce to the Pike Place Market in the early years of the last century. Today it provides for a city food security program called Solid Ground. Portland and Vancouver have similar programs. Vancouver has also entertained a skyscraper farm called Inhabitat.

Putting farms on more and more vacant lots makes sense on several levels: transportation costs would be cut for hauling produce, green spaces help reduce runoff into streams, rivers, lakes, and oceans; healthy food would be more available in more neighborhoods. And just as important urban farming reminds us food doesn’t come from the grocery store but from the land, animals and water.

So perhaps, one day, our region might realize a version of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Broadacre City, a city of tall buildings surrounded by open space and farms. Something about this concept is very appealing.

It’s the ultimate: density paired with open space and proximity to healthy food. But…maybe it’s the flying machines that would really seal the deal.

This article originally appeared on sightline.org

-----

Via WorldChanging

Personal comment:

Dans la continuité de la réflexion sur l'"urban farming", avec ici un lien historique intéressant vers Frank Lloyd Wright (Broadacre City).

|