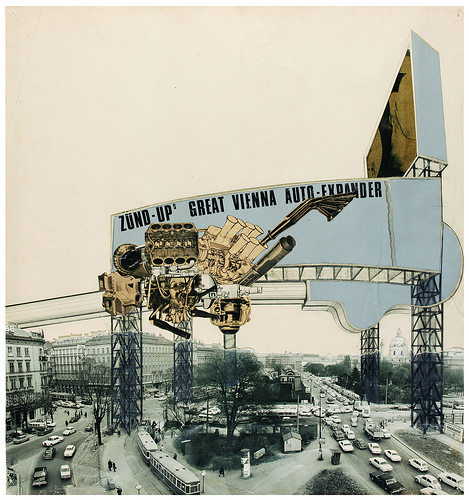

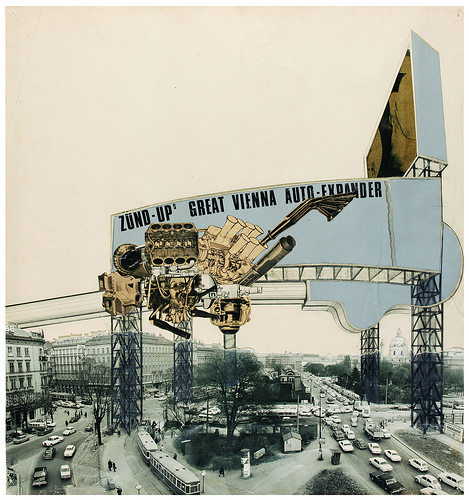

Radical young architects in the 1960s were as adept with the airbrush and the scalpel as with the conventional tools and techniques of the drawing board, writes David Crowley. Publicity-seeking design groups – with names like rock bands – demonstrated their credentials as visionaries by creating arresting images of modern life. Archigram in Britain and Haus-Rucker-Co in Austria and Dvizhenie (‘Movement’) in the Soviet Union were brilliant manipulators of the image. In their hands, the technique of photomontage – hitherto little more than an occasional practice amongst modern architects and one far more closely associated with caricature and unreality – was thoroughly renewed.

Montage allowed, perhaps more than any other medium, entirely new architectural scales to be visualised. Mechanical elements were blown up to city-size proportions, landscapes dwarfed by domestic objects, and components wrenched from their familiar settings and turned into enigmatic monuments of modernity. These were not blueprints for future structures but attempts to ‘activate the imagination’ of the viewer. What – these images asked – might the future look like in an age of electronic communications networks and lightweight and floating plastic structures?

‘Communication’ and ‘networks’ were the buzzwords of the era. Influenced by media guru Marshall McLuhan, architects conceived their buildings in terms of screens, flows of electronic data and satellite broadcasting. Tired Victorian cities could be ‘tuned up’ by being plugged into new media networks. Conventional architectural ‘hardware’ would, it was claimed, be superseded by the software of modern communications. To prove their interest in the media, Archigram – which largely existed as an occasional magazine and a series of exhibitions – took their name by compressing ‘architectural telegram’. It was, therefore, entirely logical that the architectural visions of this new generation were fashioned from fragments of the mass media. Fashion spreads and lifestyle imagery culled from the new Sunday supplements provided colourful images of tomorrow.

These architects were the last utopians of the century. Utopia was no longer an uncomplicated ideal. Their visions of future struck a strange balance between utopia and catastrophe. During these Cold War years, complete annihilation of the planet by nuclear weapons was never more than a ‘push of a button’ away. Yet, at the same time, the triumphs of the Space Race and the communications revolution delivered by satellites and teletowers made it possible to imagine a brave new high-tech world. Both disaster and perfection seem to be combined in their visionary schemes. Archigram’s Ron Herron was the master builder of this aesthetic. His schemes for a ‘Walking City’ produced in the 1960s and early 70s were disturbingly mechanical (an effect amplified by the inclusion of photomechanical reproductions of his own architectural automata or electronic circuitry). These enormous itinerant pods, augmented with turrets and towers, resembled alien craft just landed on the planet. (See Archigram on the Design Museum website.)

This anxious utopianism was also shared by Haus-Rucker-Co, a Viennese collective. In a design prepared for their 1972 exhibition, a nuclear family enjoys its leisure under a protective bubble in front of the Haus Lange (1929) designed by Modern Movement pioneer Mies van der Rohe. These contrasting visions of modernity are framed by the ruins of a city. What is unclear in this image is whether the environment outside the bubble represents the past or the future.

Above: Superstudio: New, New York, from the Continuous Monument series, 1969. Image courtesy of Deutsches Architekturmuseum.

These futuristic images were often laced with irony, an effect amplified by the techniques of montage. This was most clear perhaps in one of the most chilling images of Utopia of the era. Italian architects Superstudio proposed a Monumento Continuo (‘Continuous Monument’) – a massive linear structure, described as ‘an Architectural Model for Total Urbanisation’, which appeared to span the entire globe – in a series of virtuoso photomontages. In some images it locked familiar landscapes, such as New York City’s skyscrapers, in its freezing grip; in others it sliced through deserts and mountains. With its mute, grid-like mirrored surface, this suggested infinite capacity for extension and, as such, an escape from romantic ideas about place. Uniting the globe, the Continuous Monument appeared to be egalitarian. Yet its ordering effects were troublingly dictatorial. Accused of authoritarianism, Superstudio’s response was to claim irony: the Continuous Monument exaggerated the concept of a technological utopia to the point of absurdity. If irony could not be produced with bricks and concrete, the conventional materials of architecture, it certainly could be delivered through the media fragments combined in these remarkable montages.

Above: Photomontage for the Great Vienna Auto-Expander installation, Vienna, 1969, by the Viennese group Zünd-Up. Courtesy of V&A Images.

The work illustrated in this article features in the exhibition ‘Cold War Modern: Design 1945-70’, at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum (25 September 2008 – 11 January 2009) before travelling to other venues in Europe. Curator: Jane Pavitt; consultant curator: David Crowley. To be reviewed in Eye no. 70, Winter 2008.

Information about Haus-Rucker-Co.

Archigram site: archigram.net

See ‘Strikethrough’, David Crowley’s latest essay in Eye no. 69 vol. 18.

Bottom: Haus-Rucker-Co wearing ‘Environment Transformers’, 1968. Photograph courtesy: Archive Günter Zamp-Kelp, Berlin.