|

Slime power: A technician monitors algae-to-ethanol bioreactors at an Algenol test facility. The company has teamed up with Dow Chemical to build a demonstration plant that could end up producing 100,000 gallons of ethanol annually. The photosynthetic algae turn sunlight, carbon dioxide, and water into sugars that are synthesized into ethanol within the algae cells.

Credit: Algenol Biofuels |

Florida startup

Algenol Biofuels says that it can efficiently produce commercial quantities of ethanol directly from algae without the need for fresh water or agricultural lands--a novel approach that has captured the interest and backing of Dow Chemical, the chemical giant based in Midland, MI.

The companies recently announced plans to build and operate a demonstration plant on 24 acres of property at Dow's sprawling Freeport, TX, manufacturing site. The plant will consist of 3,100 horizontal bioreactors, each about 5 feet wide and 50 feet long and capable of holding 4,000 liters.

The bioreactors are essentially troughs covered by a dome of semitransparent film and filled with salt water that has been pumped in from the ocean. The photosynthetic algae growing inside are exposed to sunlight and fed a stream of carbon dioxide from Dow's chemical production units. The goal is to produce 100,000 gallons of ethanol annually.

There are dozens of companies in the market trying to produce biofuels from algae, but most to date have focused on growing and harvesting the microorganisms to extract their oil, and then refining that oil into biodiesel or jet fuel. Instead, Algenol has chosen to genetically enhance certain strains of blue-green algae, also known as cyanobacteria, to convert as much carbon dioxide as possible into ethanol using a process that doesn't require harvesting to collect the fuel.

Blue-green algae do produce small amounts of ethanol naturally, but only under anaerobic conditions when the cyanobacteria are starved or in the dark. Paul Woods, cofounder and chief executive of Algenol, says that his company has modified its algae so that it can produce ethanol under sunlight through photosynthesis, first by turning carbon dioxide and water into sugars, then by boosting and controlling the enzymes that synthesize those sugars into ethanol.

Another big difference for Algenol is that it doesn't have to harvest its algae to extract the ethanol, eliminating a step that has proved costly and complex for other algae-to-biofuel startups. John Coleman, chief scientific officer at Algenol and a professor of cell and system biology at the University of Toronto, says that the ethanol produced within the algae will seep out of each cell and evaporate into the headspace of the bioreactor.

"Ethanol is almost infinitely mobile in a cell, and essentially leaks out into the bioreactor after synthesis," Coleman says. "Through some various condensation steps we collect it." Other companies are working on ways to make biofuels from photosynthetic algae, including Synthetic Genomics, based in La Jolla, CA, which just signed an R&D agreement with ExxonMobil valued at up to $600 million. But efforts there have focused on oil extraction, not ethanol.

Dow is particularly interested in Algenol's process because ethanol replaces fossil fuels in the production of ethylene, which is a basic chemical feedstock for making many types of plastics. Oils from algae are less useful, says Steve Tuttle, business director of biosciences at Dow. "Biodiesel doesn't necessarily fit in with what we'd want to use as a downstream product," he says.

Tuttle says that Dow, on top of leasing land and supplying a source of industrial carbon dioxide, will also assist with process engineering and help develop advanced plastic films for covering the bioreactors. Other partners in the project include the National Renewable Energy Laboratory and the Georgia Institute of Technology. Algenol has applied for a grant from the U.S. Department of Energy that would help fund the demonstration project.

Woods is convinced that the process can be scaled up, and at a favorable cost of production. "It's our expectation to produce ethanol for $1.25 a gallon," he says, adding that the resulting ethanol gives back 5.5 times more energy than what it takes to produce it, making the renewable fuel competitive with cellulosic ethanol production. Woods notes that Algenol's approach offers another bonus: "Every gallon of ethanol made creates one gallon of fresh water out of salt water."

Algenol has also partnered with Mexico's Sonora Fields, a subsidiary of Biofields, which is planning an $850 million project that aims to produce one billion gallons of ethanol annually.

Copyright Technology Review 2009.

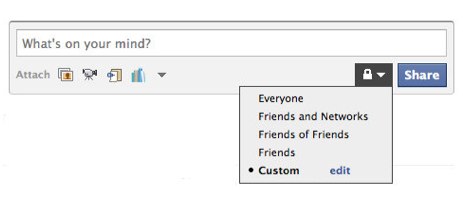

Facebook is hosting a webcast for press tomorrow about “upcoming privacy changes” to the site: the announcement will likely outline Facebook’s transition toward becoming more public – some might say more Twitter-like.

Facebook is hosting a webcast for press tomorrow about “upcoming privacy changes” to the site: the announcement will likely outline Facebook’s transition toward becoming more public – some might say more Twitter-like.

The tactic is certainly in contrast to Facebook’s early years: the network went beyond

The tactic is certainly in contrast to Facebook’s early years: the network went beyond